With Connecticut’s rainy day fund on pace to reach a

The increased reserves are a hopeful sign for taxpayers and investors alike. Rainy day funds are vital tools to help states maintain fiscal flexibility and limit painful spending cuts or tax increases when recessions or natural disasters pressure budgets. As the U.S. economy has notched its longest economic recovery since 1858, state rainy day fund balances have climbed to $68.2 billion as of fiscal 2019, National Association of State Budget Officers data show. Along with boosting deposits, many states have also used the rebound as an opportunity to strengthen rainy day fund rules to ensure that deposits and withdrawals are more tightly regulated and to take the increasing volatility of their tax revenues into account.

Indeed, states’ growing reliance on income taxes, especially on capital gains that can fluctuate with the stock market’s gyrations, has contributed heavily to revenue volatility. The

“States that fail to maintain adequate reserves may face credit rating downgrades and the uncertainty of implementing fiscal policies with little or no cushion for emergencies,” according to a new Volcker Alliance working paper,

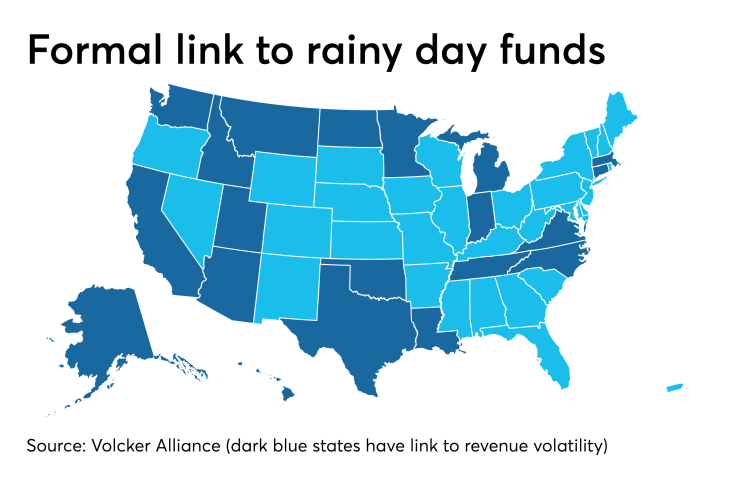

Recognizing these realities, 20 states have put into place policies linking rainy day funds to revenue volatility, according to Volcker Alliance research.

Among states following this rule is California, where voters in 2014 passed a constitutional amendment that increases budgetary savings and links them to volatility.

Known as Proposition 2, the amendment requires annual deposits into the state Budget Stabilization Account of 1.5% of general fund revenues plus any capital gains tax proceeds that exceed 8% of general fund revenues. “Right now, California has $19.5 billion in total budget reserves—that’s the highest they’ve ever been,” state Legislative Analyst Gabriel Petek told attendees at a recent

Connecticut has also taken steps to factor volatility into reserve balances after policymakers realized that revenues were fluctuating dramatically because of the state’s dependence on capital gains taxes paid by hedge fund managers and others in the financial services industry. A progressive income tax for individuals, with rates of 3% to 6.99%, only exacerbated the volatility. In response, legislators in 2017 limited the amount of personal income tax collections that could be used to balance the budget to an exact sum, which increases over time. The cap was set at $3.1 billion for 2019 and $3.3 billion for 2020. Any amount above this so-called volatility cap is automatically transferred to the state’s Budget Reserve Fund. To reassure municipal bond investors, Connecticut also passed a so-called bond lock requiring that as long as any general obligation debt issued from May 15, 2018, to June 30, 2020, was outstanding, the state must comply with the volatility cap for stocking the reserve fund.

Some states that don’t formally tie rainy day fund reserves to revenue volatility have nonetheless taken steps to boost savings. During the Great Recession and its immediate aftermath, Georgia, for example, depleted its

When deciding to strengthen rainy day funds, state officials must make “real political tradeoffs,” Petek said. “It’s not always easy for policymakers to think further ahead down the road to when the next rainy day might occur. And we don’t really know what the size of the next deficit will be in a downturn.”

But for states, the political and economic consequences of maintaining inadequate reserves—or no reserves at all—may be even greater. Now is the time for states to boost their budgetary savings and improve rainy day fund rules rather than wait until the economy’s record run falters.