“Islands are the canary in the coal mine in this situation. They are sending a message now that if we don’t act — and act boldly — it’s going to be too late," former President Barack Obama, said while speaking at COP26, Glasgow, Scotland, on Nov. 8.

One challenge of garnering official and public attention for the necessity of urgent, programmatic response to global warming is its seeming lack of immediacy. The potential of harm and danger is often described futuristically in terms of a decades-long timetable.

Not so for Hawaii. The consequences of climate change for this island state are broadly evident. So is its official response.

For example, according to ProPublica, among Hawaii’s three major islands, about 25% of its beaches have been lost to rising sea levels. The State of Hawaii Climate Portal includes an estimate of the loss of about 13 miles of beaches to date. Further, sea level rise continues at about one inch every four years.

Hawaii as a collection of islands reflects the similar challenge of global warming for the island nations of the world that in 1990 organized the Alliance of Small Island States to highlight the more immediate impact of global warming with respect to their circumstances. The organization had formal representation at the just-concluded Glasgow COP26 serving as firsthand witnesses to the dire consequences of a changing climate to the world’s nations currently less effected.

For Hawaii, the starkly evident problem for its future has prompted meaningful response by its public officials over several years captured in succinct fashion by the comments of its current governor, David Ige, opening the state’s 2020 climate conference: “What we used to call climate change is more accurately described as a climate crisis.”

Ige also traveled to Glasgow COP26. His state’s substantial efforts to address its climate circumstances will be insufficient unless the countries of the world adopt comparable goals and practices.

As a part of its climate planning process, the Hawaii Climate Change Mitigation and Adaption Commission released its

Although symbolic, the Hawaiian Legislature in April approved a resolution declaring a “climate emergency”— the first American state to do so.

Note that as a part of its climate-related efforts, Hawaii appears equally diligent in disclosing its challenge to its bond investors as reflected in its most recent offering document for its highway bonds. There is a page of climate disclosure with a link to a state report on the topic. (

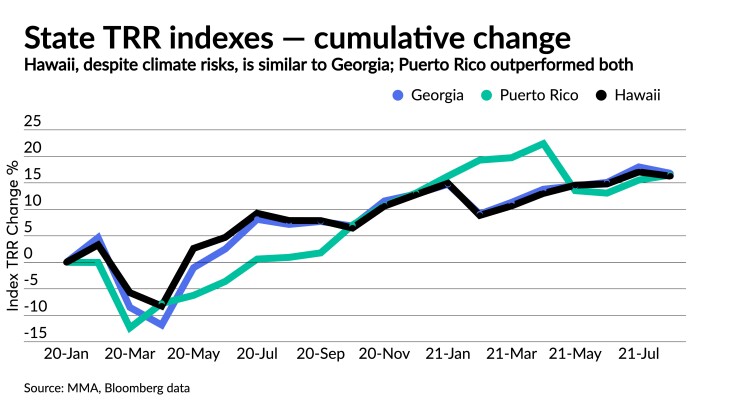

Yet, this elevated level of climate challenge for Hawaii, its considerable public efforts to address the problem, and its detailed summary in state bond offering disclosure documents do not seem to have meaningfully impacted the prices at which Hawaiian municipal debt trades.

MMA compares the evaluation of Hawaiian municipal debt to that of two other U.S. geographies: Georgia and Puerto Rico. As the analysis demonstrates, its debt is evaluated in line with other municipal debt thus paying little, if any, climate penalty given the depth of its challenge.

Hawaii should be commended for acknowledging the depth of its climate problem and the transparency by which it proceeds.

While it shouldn’t be punished for its openness, the trading levels of its debt likely do not reflect its challenge — one which it alone cannot solve. Its sea level threat has risen and will continue to do so until the curve reflecting global warming is flattened.

Christopher Hamel is a senior fellow with Municipal Markets Analytics Inc.