"This agreement represents an incredible milestone on the road to financial recovery; for the first time in a very long time, every single one of our pension funds is on a path to financial security … I know the solutions are not easy, but we will finally be honest about the cost of running the City …" – Mayor Rahm Emanuel (Aug. 3 press release)

The City of Chicago has four pension plans, not counting the teachers' plan, which is the responsibility of the school district. Combined, these four plans are among the worst funded public pension funds in the country. Worried employees want to be assured that their pensions will be honored. Worried taxpayers want to know what that will cost them.

Some progress has been made. The employees have agreed to some plan modifications, and the city has agreed to substantial tax increases dedicated to funding the pensions.

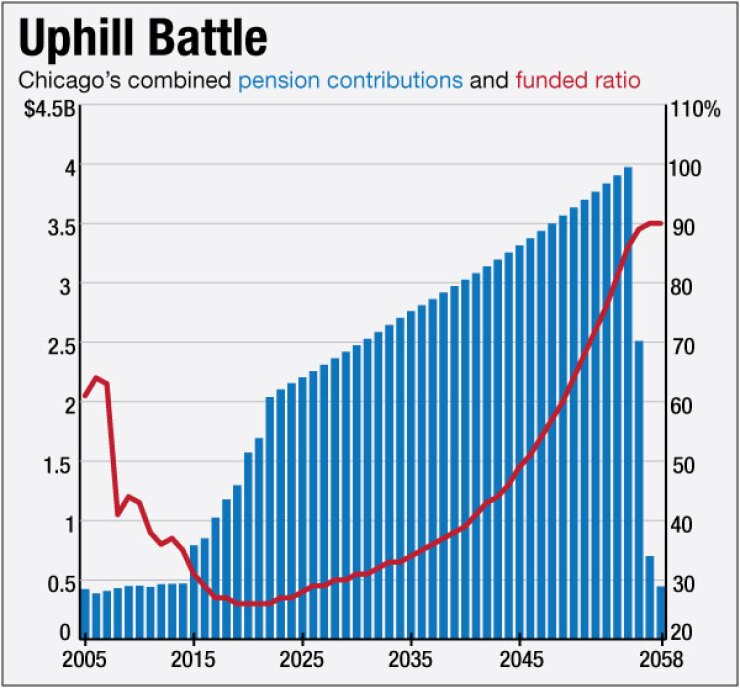

Mayor Emanuel's statement excerpted above was occasioned by the latest such agreement. His statement might be read to suggest that the city has finally overcome the challenges of funding its pension commitments. The reality is far worse, as the adjacent graph shows.

In the graph, the blue bars show Chicago's annual contributions to the four pension plans combined, and the red line shows their combined funded ratio. Where possible, the graph uses recently released official projections. In all other respects, the graph reflects our own projections based on official actuarial assumptions and statutory funding requirements.

For the 10 years through 2014, Chicago contributed less than $470 million per year to the plans. These contributions were insufficient even to maintain the funded ratio, which went from a poor 61% at the end of 2005 to a dangerously low 31% at the end of 2015.

By 2019, the city's annual pension contribution is expected to be $1.3 billion – an increase of $827 million, or 176%, above the 2014 contribution. Over the three years thereafter, the annual contributions are expected to jump another $741 million, to $2.0 billion in 2022. All of Chicago's recent and proposed tax increases combined will be insufficient to fund these increases. We estimate the shortfall will be $647 million in 2022 alone.

After 2022, we project contributions will increase every year through 2055. Over that period, the annual contribution will increase by another $1.9 billion, to $4.0 billion in 2055 – 8½ times what the city was paying in 2014.

Do these steep increases provide steady progress toward proper funding? No. In fact, the plans' funded ratio will actually drop over the next several years – from 31% in 2015 to 26% in 2021 – and their unfunded liabilities will increase until 2033. It will take until 2030 for the funded ratio to return to 31%; until 2050 for the funded ratio to be restored to where it was in 2005 (61%); and until 2057 for the ratio to reach 90%.

The graph's projections assume that the official actuarial assumptions prove correct, and Chicago will make the annual contributions mandated by law. If history is any guide, these assumptions will prove overly optimistic, and much more money will be needed.

For example, the city's pensions continue to assume that their investments will earn 7.5% per annum. This assumption is dubious. Many public pension plans, including Illinois's largest, have reduced their assumed return to 7.0% or below. This change would significantly worsen the numbers discussed above.

To be clear, we are not attacking pensions. To the contrary, we believe employees should not be put in the position of serving the city for many years yet left guessing whether the city will be able to pay their pensions. The only way to avoid this is for the city to contribute actuarially sound amounts to the plans every single year. By ignoring this precept, the prior administration dumped a big mess on Mayor Emanuel's lap.

While Mayor Emanuel has chipped away at the problem, the city has come nowhere close to identifying a solution. While it will take years to fill the present deep hole, surely the hole should not be dug deeper still. Yet that is exactly what the city proposes to do.

In our view, Chicago must, at a bare minimum, contribute enough every year, including 2016, to ensure that the plans' funded ratio not drop below, and that their unfunded liabilities not exceed, 2015 levels. We estimate this would add $1.1 billion to the 2016 contribution. If the city cannot muster the resources and political courage to take this first step now, surely the city will lack the resources and discipline needed to dig out of a far bigger hole down the road.

It is responsible to ask stakeholders to share the burden of a reliable solution. But absent a reliable solution, sacrifices made now are likely to serve no goal other than to kick the can down the road yet again.

Mark D. Brodsky is the Chairman of Aurelius Capital Management, LP, an investment manager. This essay does not constitute investment advice or a solicitation.