CHICAGO — Since its creation by the Wisconsin Legislature last year, the Public Finance Authority is spreading the message that while it may have a northern address, its boundaries as a conduit issuer extend across the country.

It is a message heeded by a handful of not-for-profits and other borrowers that have used the agency to access the tax-exempt market in recent months, but it’s also one that has ruffled the feathers of existing local and state-based conduits that question the need for a national issuer and worry about the competition.

“The Public Finance Authority is out there to create an alternative at a time when communities are really struggling to generate economic activity,” said Liz Stephens, the PFA’s Wisconsin-based program manager. “Access to capital is really difficult and the PFA is there to provide another tool and resource to help local governments.”

The authority is formally a subdivision of Wisconsin established under legislation signed by former Gov. Jim Doyle last year. The agency promotes its ability to issue tax-exempt conduit bonds for public and private entities nationally for projects with public benefits to promote economic development, industry, infrastructure, and affordable housing. Because of its national scope, the PFA can serve as a one-stop shop for projects that span multiple jurisdictions.

While a handful of state-based authorities have the statutory power to issue bonds for projects outside their borders, “the PFA is the first authority created for the primary purpose of supporting projects anywhere in the country,” said Roger Davis, a San Francisco-based attorney with Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP and a co-author of the Wisconsin legislation.

The agency is promoting its ability to provide access to the tax-exempt market where none may exist, or easing the process and sometimes the cost for others that might face a tougher time in their local or state jurisdictions. One critic counters that, at least in Illinois, there is no void to fill.

“Any purported need in Illinois for conduit financing can be met by the Illinois Finance Authority or home-rule units of government or regional development authorities,” said executive director Christopher Meister. “This is an attempt to usurp the policy choices of individual states.”

“The PFA is more flexible on some of the conditions, especially those imposed on less creditworthy institutions,” Davis said. In New York State, where authority for industrial development agencies to issue debt on behalf of nonprofits lapsed two years ago, Davis said the PFA provided the means for Chaminade High School in Mineola, N.Y., to access the market with an $8.7 million issue.

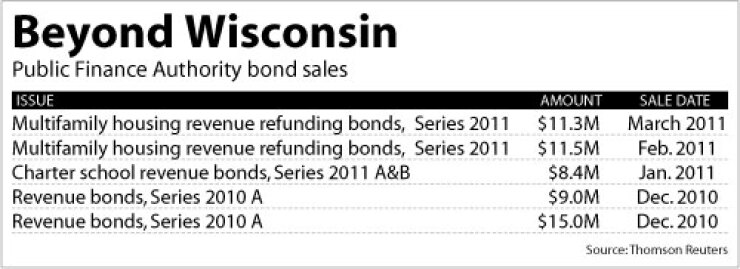

Since opening its doors late last year, the Wisconsin-based authority has also served as conduit for two Colorado charter schools, Denver-based Highline Academy Charter School and the Aurora-based Global Village Academy.

It also issued $24 million of multifamily housing bonds for two affordable rental housing projects in Jacksonville, Fla., and served as conduit for the Wisconsin-based Adams-Columbia Electric and Central Wisconsin Electric Cooperative’s Midwestern Disaster Area bond and recovery zone facility bond issues. About a dozen deals are pending.

In Illinois, Gov. Pat Quinn last year signed legislation that broadened the IFA’s issuance powers to include cross-border financings, a measure pushed as necessary to compete with other states with similar capabilities and the PFA.

Under the Wisconsin legislation, existing state authorities such as the Wisconsin Health and Educational Facilities Authority and the Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority have the right of first refusal on financing projects.

“That is not a courtesy they have extended to their sister state,” Meister said.

The PFA is sponsored by the National Association of Counties, the National League of Cities, the Wisconsin Counties Association, and the League of Wisconsin Municipalities. Its board is made up of five officials from local Wisconsin governments, plus two members from out of state: Jeannie Garner, director of insurance and financial services for the Florida League of Cities, and Maricopa County, Ariz., finance director Shelby Scharbach.

NACo looked to establish a national authority and found a welcome home in Wisconsin. Its structure was somewhat modeled after the California Statewide Communities Development Authority, which Davis works with as a bond counsel. Like the CSCDA, the PFA contracts with HB Capital Resources Ltd. to manage its operations. Stephens is an employee of HB, as are a handful of other program managers used by the PFA.

California Treasurer Bill Lockyer, whose office operates several conduits, has been a critic of the CSCDA model of being operated by a private entity, saying it comes under limited governmental scrutiny. Los Angeles County earlier this year withdrew from the CSCDA to retain local control over financings.

The CSCDA was created in 1988 through the sponsorship of the California League of Cities and California State Association of Counties, under the state’s joint powers law that allows any two or more governmental agencies to join forces to create a JPA. The state passed greater disclosure requirements on JPAs that serve as conduits in 2009.

The CSCDA serves as poor model, according to Lockyer spokesman Tom Dresslar. “That is not how a public agency should be run,” he said.

Illinois’ Meister said his concerns are similar. “Under state statutes, the IFA serves an essential public function and there is a direct line of accountability to all branches of Illinois government,” he said. “This model cuts the cord of essential accountability and transparency.”

The oversight Meister refers to includes annual reviews by the state auditor. The agency’s board is picked by the governor and approved by the state Senate. The IFA must also comply with state ethics rules.

PFA officials believe those concerns are overblown and say competition will serve borrowers well. They also counter that the agency faces plenty of accountability. “We are here to increase volume” by providing an avenue for borrowers to the tax-exempt market that might otherwise not have one or find it too costly or cumbersome, Stephens said. “We are filling a void.”

On its website, the PFA declares: “Providing eligible, creditworthy borrowers with easier, lower-cost access to capital to the benefit of the patients, students, seniors and low-income residents they serve is yet another of PFA’s missions. … Like other consumer groups who make choices based on factors that impact their own bottom line, consumers of tax-exempt debt choose a mode of issuance based on those same concepts: cost, efficiency, transparency and accountability.”

Stephens stresses that the agency faces multiple layers of oversight. Any project must get approval from the local jurisdiction and she notes that the board is made up mostly of elected officials. The PFA complies with state open-meetings laws and must submit its financials annually to the Legislature and governor’s staff.

In addition to its cross-border issuance, the agency eases access for below-investment-grade credits by lowering the bond denominations needed to sell to qualified investment buyers. The agency’s bonds are not exempt from state income taxes, and any volume cap needed for private-activity bonds comes from the local jurisdiction. Borrowers are not required to use Orrick or any firms recommended by the PFA.

The reasons behind borrowers’ use of the authority to date have varied. The agency said the local Florida issuer declined the deals and the Colorado charter schools required quick action. The PFA provided the only route to access the tax-exempt market for the Wisconsin cooperatives, according to officials.

“As a result of this new opportunity made possible by recently enacted legislation in Wisconsin and the assistance of the Public Finance Authority, we are able to upgrade our electrical infrastructure at a savings of millions of dollars to our ratepayer members,” said Greg Blum, CEO of Central Wisconsin Electric.

Other industry officials see pros and cons to a national authority. Any effort that increases access to financing could help local development and increased competition could lower issuance fees. But the lack of regulation raises questions, said Toby Rittner, president of the Council of Development Finance Agencies, who expects to see local, state and possibly federal reaction. “There is a potential for backlash,” he said. “The question is, did Congress intend for a Wisconsin issuer to issue tax-exempt bonds for a Texas project?”