WASHINGTON – The Trump administration is expected to finally unveil its long-awaited infrastructure plan in January, but some muni market participants worry any legislation for federal funding might cut private activity bonds for revenue.

“The federal cash register is empty after tax reform,” said Chris Hamel, managing director and head of municipal finance at RBC Capital Markets, pointing to the fact that the tax bill is expected to add almost $1.5 trillion to the federal deficit over 10 years.

“I worry that, given that the federal cash register is empty, will the issue of some limits on PABs be revisited as a pay-for in any expected infrastructure investment legislation?” he asked.

“I’ve heard that concern too,” said Michael Decker, managing director and co-head of municipal securities at the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. “Once a revenue raiser gets floated or ends up on a list, then it’s there forever.”

The House tax bill had initially proposed to terminate tax-exempt private activity bonds by Dec. 31.

“It’s good for the [municipal securities] industry to understand that the fight over PABs is not necessarily over,” said Hamel.

But Hamel, echoing other infrastructure experts, said, “I think the prospects for meaningful infrastructure policy reform are slim.”

Trump administration officials have been meeting with infrastructure and transportation groups over the last two weeks about the infrastructure plan the president is supposed to unveil in January, possibly around the time of his State of the Union address on Tuesday, Jan. 30. And on Dec. 22, Trump tweeted "At some point, and for the good of the country, I predict we will start working with the Democrats in a Bipartisan fashion. Infrastructure would be a perfect place to start. After having foolishly spent $7 trillion in the Middle East, it is time to start rebuilding our country!"

“They’re serious this time, I think,” said Jeff Davis, senior fellow and editor of a weekly news report at the Eno Center for Transportation. Transportation Department Secretary Elaine Chao has repeatedly promised the plan would be released every few months this year.

The centerpiece of the plan is expected to be $200 billion of direct federal funding that would be used to leverage another $800 billion for infrastructure projects over a 10-year period.

Half of that money would be used for 20% federal share of incentive grants to states. Another 25% of the money would be used for grants for infrastructure projects in rural states and the final 25% would be for the big, high-profile, so called “transformative projects” picked by the Commerce Department.

“Apparently they’re going to prioritize projects where a state or local government has created or identified a revenue stream that can support a project over its life cycle,” added Michael Decker, managing director at co-head of municipal securities at the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. “They’re really going to encourage state and local governments to take on some of the responsibility themselves.”

Federal Funding

Right off the bat, infrastructure advocates are bashing the $200 billion of direct federal funding over 10 years as way too low.

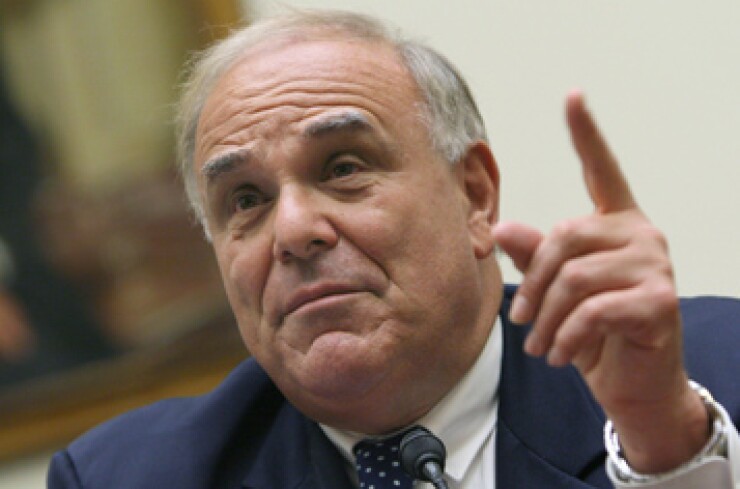

“The president is whistling past the graveyard if he thinks $20 billion a year additional investment in American infrastructure by the federal government is going to do anything,” said Ed Rendell, the former Pennsylvania governor who co-founded Building America’s Future, a bipartisan coalition of elected officials dedicated to promoting infrastructure investment.

“It is far too little of an investment,” said Rendell. The American Society of Civil Engineers gives America’s infrastructure a national grade of D+ and says it will take $2 trillion over 10 years to move that grade to fair from poor, he said.

It would take $100 to $120 billion to build a high speed rail line between Washington, D.C. and Boston, he said. Yet the president is proposing federal spending of only $5 billion per year over 10 years for big projects.

“Who is he kidding?” asked Rendell.

Rendell and others said Trump and Congress should have included infrastructure initiatives in the tax bill to raise the federal gas tax, which hasn’t changed since 1993, and index it to inflation to stabilize the Highway Trust Fund. They also should have used funds from the repatriation of companies’ overseas earnings to pay for infrastructure rather than to pay for the tax bill itself.

“I think the tax bill was a missed opportunity,” said Jack Schenendorf, of counsel at Covington & Burling.

“The other thing they blew [in the tax bill] was not fixing the Highway Trust Fund when they had a chance,” said Casey Dinges, a senior managing director at the ASCE.

The HTF, which helps fund transportation projects, has been dwindling as cars have become more fuel efficient. Right now it’s spending about $10 billion more than its taking in in federal gas tax revenues and it will be “running on fumes” by 2020, said Davis.

As for PABs, Rendell said the administration and Congress “can’t cut them because if the president is contemplating any private involvement in infrastructure there has to be private activity bonds.”

80% State Matches

Another concern is that the plan will ask states to provide 80% matches for 20% federal incentive grants.

“I don’t think the states are looking for this kind of arrangement,” said Dinges.

He and others said its ironic the administration wants to ask states to put up 80% matches for 20% federal funding after Congress took away some of the tools states had for infrastructure funding in the tax bill.

“There were some pretty significant tools for infrastructure that were thrown out by the tax bill, like advance refundings,” said Emily Brock, director of the Government Finance Officer Association’s Federal Liaison Center. “Unfortunately [tax-exempt advance refundings provided] the opportunity to save money to make infrastructure investments and now that tool is gone.”

The big question on the incentive grants, said Davis, is whether 20% is that total amount of direct federal funding an issuer can get for an infrastructure project or whether the 20% can be combined with funds from other federal programs, such as the Federal-Aid Highway Program.

He said trying to convince states to accept federal funding that totals 20% and requires an 80% match “will really be a hard sell.”

“Most of the state departments of transportation, the Chamber of Commerce and the construction industry have had a consistent message all along,” said Davis. “They say: ‘New infrastructure programs are nice but the top priority should be to make sure existing programs don’t run out of money in 2020 and put them on a solvent basis permanently.’ The administration’s proposals to date have dodged that issue.”

Davis said that the last major transportation bill – Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act, which was enacted in December 2015 -- authorized $305 billion over fiscal years 2016 through 2020 for highway, rail, and other programs.

Sources transportation experts said they think public-private partnerships (P3s) will be in the administration’s infrastructure plan, even though Trump, who once saw them as a major part of the plan initially has since seemed to turn against them.

“I still think P3s and finding a way to bring the private sector into the fold is going to be a piece of the plan,” said Jim Tymon, chief operating officer of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials.

Schenendorf agreed. “I think P3s will be an important part of the overall proposal.” But he added that he thinks administration officials have learned from talking to folks that P3s don’t work in some parts of the country such as rural areas.

Slim Hope for Legislation

Many infrastructure experts, pleased that Trump is preparing to release his infrastructure plan, are not optimistic about his being able to get it through Congress.

RBC Capital’s Hamel said there are two major reasons to doubt there will be legislation.

“The till is empty,” he said, referring to the tax bill’s increase to the deficit.

“My fear is they used all of their dry powder to make tax reform work,” he said, explaining he thinks the administration is going to be “hard pressed” to find $200 billion to pay for federal funding for infrastructure.

Davis agreed, saying, “I think the ‘going to the well on let’s not pay for it’ may have run out.”

Another reason for skepticism, Hamel said, is that “anything that is going to be passed will need 60 votes in the Senate.”

The only way the Republicans were able to pass the tax bill was to go through a reconciliation process that required only a majority, rather than two-thirds vote in the Senate.

Also, House and Senate Democrats are still smarting from the fact that they were left out of the process of debating or adding any input to the tax overhaul bill.

Even though Democrats and Republicans seemed to have some common interest on infrastructure at the start of last year, there is a great deal of “political toxicity” right now, said Dinges.

“The Democrats, even though they love infrastructure, are they going to want to dance to help the administration?” he asked.

Also, “it seems the Democrats and the administration are starting from way different perspectives” on infrastructure, said Dinges.

Senate Minority Leader Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y. introduced a bill last January on behalf of Democrats that would have provided $1 trillion in direct federal spending on infrastructure, rather than just $200 billion.

If the Democrats are still bitter about tax reform, Dinges said, they could try to delay any infrastructure legislation, hoping to win seats in the mid-term elections and take over the majority of either or both the House or Senate to ensure that this time they can play a major role.