This article is part of The Bond Buyer’s multi-platform series on the future of infrastructure:

In this four-part series, The Bond Buyer looks at the changes this infrastructure moment could bring to landscapes and markets across the nation. It includes four longform feature stories running every other Tuesday for the remainder of 2021, beginning November 16th and concluding December 28th; a four-episode companion podcast series beginning November 30th; and a live video December 28th on our 'Leaders' channel, all hosted by the author.

By now, most Americans are familiar with a few major aspects of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which President Biden signed into law in November. It's big, with $550 billion of new federal spending over the next five years. It passed Congress with bipartisan support after arduous negotiations. It invests in tangible or "hard infrastructure" — and nearly 70% of respondents in a recent NPR/Marist poll said they are optimistic that it will improve roads and bridges. It's a precursor to the even larger Build Back Better bill (BBB), which would fund many of the so-called "human infrastructure" programs that make up the rest of the Biden administration's agenda.

You might also expect that the IIJA — a gigantic attempt to upgrade transmission and transportation networks around the country — would take substantial steps toward meeting the administration’s sustainable energy and climate change goals. The White House wants to cut U.S. greenhouse-gas emissions in half by 2030, and, in keeping with a return to the 2015 Paris Climate Accords, to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. And the president has sold the package by saying it will "turn the climate crisis into opportunity."

So we analyzed the energy provisions of the IIJA to see just how much it seizes the chance to fight climate change. We’ve found the law will indeed bolster emerging technologies, make energy production and consumption more efficient and fortify buildings and the power grid against climate-related disasters. On its own, however, it doesn't have nearly enough force to bring emissions down to a level where rising temperatures will be manageable rather than disastrous.

For more than a decade, lawmakers in the United States have crafted energy policy within a political context that simply does not allow for strongly increasing regulation of fossil-fuel companies or subsidizing competitors they regard as dangerous. As just one example, in 2010, Democratic leaders didn't bring a national carbon cap or a renewable-energy standard to a vote in the Senate, even though they controlled 59 of that chamber's 100 seats; they knew they didn't have the votes to pass either idea. More recently, Sen. Joe Manchin, a West Virginia Democrat whose coal brokerage holdings have made him a millionaire, torpedoed the Clean Energy Payment Program (CEPP), a key plank in Biden's agenda that would have paid utilities to switch to sustainable energy sources.

The IIJA is crammed with clever ideas and creative initiatives that will prepare Americans to live, work and travel in a more resilient, more electrified, lower-carbon future. But it doesn't regulate carbon dioxide or mandate emission reductions in the here and now, and it hardly supports renewable-energy producers who are already in business. If you want to imagine the situation now facing the nation, picture buying a house that's outfitted with strong weatherproofing, speedy broadband and an electric-car charging port in its garage, but in danger of failing inspection because of contaminated air.

"As a vehicle of green industrial strategy for a long-term, economy-wide transition to clean energy, the IIJA is an arguably unprecedented step in the right direction," an August report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a policy research organization in Washington, D.C., stated. "As a climate strategy to meet the immediate goals of a rapidly dwindling carbon budget, it is a dereliction of duty."

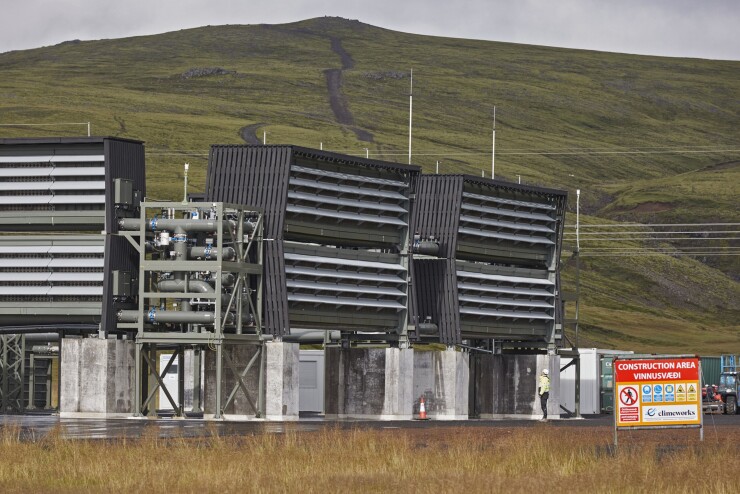

This paradoxical result — infrastructure policy that plans for 2050 outcomes without hitting 2030 goals along the way — is clearest in its approach to the power sector, which has reduced carbon emissions by 40% over the past 15 years and still affords the biggest and cheapest chances for further cuts. The IIJA directs nearly $40 billion to research and development, targeting three key early-stage technologies in particular for support from the Department of Energy (DOE). First, it establishes a major federal commitment to carbon capture: $12.5 billion will go to an array of demonstration projects and pilot programs for sequestering and transporting carbon dioxide produced by industrial sources. It even offers $115 million in prizes for tech that grabs CO2 directly from the air.

Similarly, the IIJA greatly expands R&D funding for hydrogen. It puts $9.5 billion toward establishing regional hubs, demo projects and recycling programs for safely synthesizing what could be the world's cleanest energy source. (When used as a fuel, hydrogen produces only water as waste.)

The new law also allocates $2.5 billion to two projects, with DOE splitting the costs of nuclear reactors where private companies hope to demonstrate advanced technologies. One is in Wyoming, where TerraPower is erecting a facility that would generate 345 megawatts at the site of an old coal plant. The other is in Washington state, where X-energy is building a 320-megawatt reactor using a combination of encased fuel pebbles and helium coolant that could both cut capital costs and reduce the chance of meltdowns. (Last year, the United States had the capacity to generate about 1.2 million megawatts of electricity.)

There are good, even critically important, reasons to nurture infant power producers. Many will have to grow much larger if the U.S. ever hopes to decarbonize, much less lead the world in doing so. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated last year that 34% of the carbon dioxide cuts needed to shift to net-zero will come from tech that's currently at the demonstration phase or even newer. "A lot of the funding here will help make these low-carbon technologies accessible," says Morgan Higman, a fellow at CSIS. "It also helps demonstrate to the private market that there is interest in these areas."

It can take a long time for new energy technologies to move from the prototype stage to capturing even 1% of their markets — 20 years for LED lights, more than 40 for cars powered by lithium-ion batteries. Subsidies could help accelerate their development and adoption.

The federal government actually has a track record of successfully doing just that. In 2009, President Barack Obama's economic stimulus package earmarked $25 billion for amping renewable energy generation. The money funded direct payments and guaranteed loans to solar and wind power companies, and started the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Energy (ARPA-E), a green-tech incubator. Opponents derided the assistance, particularly after Solyndra, a maker of solar panels, defaulted on a federal loan of more than half a billion dollars. But $4.6 billion in guarantees also went to the first five 100-megawatt solar-powered plants in the U.S. Completed between 2013 and 2015, they are still operating and have a collective capacity of 1,502 megawatts.

The green-energy stimulus launched renewables into an upward spiral: As more projects came online, competition increased, technology got better, prices fell — and even more projects came online. (The DOE even wound up earning more from interest payments on the loans it made than it lost to defaults, too.) "Decisive public policy support … delivered through the stimulus package reversed the grim outlook for solar power in 2009 and jump-started a decade-long boom," concluded a report issued last year by the American Energy Innovation Council, a group of corporate leaders, and the Bipartisan Policy Center, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank.

From 2009 to 2019, the price of electricity from large-scale solar arrays dropped 89%, and solar power production rocketed by almost 5,000%. Wind energy prices and generation followed a similar trajectory. And today, power companies need to charge their customers just $30 to $41 per megawatt-hour to break even on building a new large-scale solar facility and $26 to $50 for a new wind farm, compared with $65 to $152 for a new coal plant, according to the investment firm Lazard.

There's still enormous room for renewables to grow. Solar and wind power each added record capacity in 2020, but together, they still generate just 11% of the nation's electricity (compared with about 40% for natural gas and 19% for coal). Additional technological advances could further cut the costs of harvesting, storing and transmitting sustainable energy, making it even more attractive for producers to go green. Greater financial support could quicken the rate at which renewables scale up, for example by helping to link rooftop or community solar arrays into utility-size networks. To decarbonize, the U.S. needs both to happen, and as quickly as possible.

But the new infrastructure law dedicates just $100 million to wind power R&D, and only $80 million to solar energy. Of the funds appropriated to the Department of Energy, 64% go to establishing a long-term industrial strategy and fostering innovation, while just 21% mitigate carbon emissions, according to CSIS. As a proportion of all of the IIJA's new spending, renewable energy gets 0.08%.

Those numbers look even skimpier considering the new law also provides billions of dollars to an industry that's more mature and less successful than solar or wind. Apart from supporting the DOE's two advanced nuclear projects, the IIJA will fund a Civil Nuclear Credit Program to shore up nuclear operators who are already operating traditional plants. Nuclear power generates just under 20% of the country's electric supply. But with typically huge costs, most of its producers find it hard to make money, and were likely to retire reactors with 50,000 megawatts of capacity by 2031, according to Rhodium Group, a research institute in New York. To prevent those greenhouse-gas-free plants from leaving the grid, the new program will simply spend $6 billion to keep them running.

That's a bailout with an understandable goal, but it's still a bailout. And it reflects a level of bipartisan support in Congress that just doesn't exist right now for solar or wind power. "Part of it is that to a lot of folks, infrastructure means go build roads, bridges, broadband, but not necessarily build power grids that are resilient to and mitigate climate change," says Ben King, a Rhodium Group senior analyst. "The other part is that the natural gas industry, the oil industry, the coal industry see continued progress toward decarbonization as an existential threat to their current business model."

Overall, the U.S. economy pumps more than 4,500 million metric tons (MMT) of carbon dioxide into the air every year, a number that needs to drop to about 3,000 MMT by 2030 for the country to stay on a path toward net-zero emissions. Under laws and regulations now in place, it would drop to 4,210 MMT, according to an October analysis by the Zero-Carbon Energy Systems Research and Optimization Laboratory at Princeton University. The IIJA would tug it down just a bit further, to 4,153 MMT — still more than a billion tons short of the 2030 target. The Princeton researchers say the new law would result in a "nominal reduction below existing policy."

To be fair, the IIJA spends heavily in all kinds of areas where better infrastructure could lead to greater carbon reductions. $66 billion for Amtrak and $39 billion for public transit will modernize fleets and add stations, which could reduce delays and shift commuters from cars to trains and increasingly electrified buses. $65 billion to repair and rebuild the power grid should not only make systems more resilient, but add transmission lines for solar and wind power. $25 billion for airports could reduce congestion and emissions. $21 billion to clean up pollution will include capping orphaned oil and gas wells, preventing methane from oozing into the atmosphere.

The new law is particularly shrewd about creating ways for greener energy use to eventually become part of Americans' everyday lives, providing billions more for electric vehicle charging stations, lower-carbon school buses and a Safe Streets program to encourage walking and cycling. "People are starting to recognize there are electric cars everywhere, but not seeing charging stations," says Hayley Berliner, a clean energy advocate at Environment America who works to electrify New Jersey's transportation sector. "Once they see the charging stations, they will feel more comfortable buying the cars. If I were aware of something all the time, I would be more accepting of it. That's true of anything."

These indirect and cultural effects are hard for statistical models like Princeton's forecast to include, but there's little question that over the long haul, they will contribute to cleaner and more efficient energy use, and to shifting toward a lower-carbon future. Absent other changes, however, average temperatures will keep creeping upward, and climate- and weather-related disasters will keep getting more frequent and more damaging. Biden's progressive critics are harsh but essentially correct when they say the IIJA is "not a climate bill."

The Biden administration's full-frontal fight against climate change takes place instead in the pages of the Build Back Better Act, which is still bottled up in negotiations among the White House and Senate Democrats. BBB is known largely as a catch-all for $1.75 trillion in domestic spending, including funds for child care programs, universal pre-K and Obamacare subsidies. But it would also make massive environmental investments, devoting about as much to climate action as the entire IIJA does to infrastructure, according to the Sierra Club.

BBB envisions prolonging and broadening tax credits to clean energy producers; it would provide nearly $200 billion in breaks over the next 10 years to companies that produce and invest in electricity from solar, wind and other renewable resources. It would also offer $41.5 billion in credits to individuals who make their buildings and property more energy-efficient, $20.3 billion to businesses who use advanced, low-carbon manufacturing and $19.8 billion for buying electric vehicles.

BBB would also supplement the infrastructure law's spending on EV charging stations, public transit and rail. It would set up a Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, essentially a green bank to support agencies and organizations that finance clean energy projects. It would reinstate and expand excise taxes that expired in 1995 on the production of dangerous pollutants, including methane. But the tax breaks, essentially shifting the costs of transitioning to low-carbon, are key. "The most important thing in that bill is the extension and expansion of the clean electricity tax credits," says King. "Over the past 15 to 20 years, those have been some of the largest policy contributors to solar and wind taking off as they have. They are absolutely critical to getting the deployment of clean generating technologies that we need into the power sector."

This fall, the Biden administration had to drop CEPP, its proposed Clean Energy Payment Program, from BBB at Sen. Manchin's insistence. At a cost of an additional $150 billion over 10 years, CEPP would have provided grants to electricity suppliers that provided increasing amounts of clean-sourced energy to its customers, and penalized those that didn't. That direct cash, carrots-and-sticks approach would likely have been very effective: the Princeton researchers estimate that by itself, CEPP would have cut carbon dioxide emissions by more than 350 million metric tons per year. Without the program, the IIJA and BBB combined are projected to cut CO2 by about 900 MMT. That's not enough to hit the 2030 target, but it would keep the U.S. within shouting distance of the pathway to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Ultimately, then, the numbers say that to get to the point where the U.S. economy returns a ton of carbon to the geosphere for every ton it releases into the atmosphere, the country will need Build Back Better, without further weakening, on top of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, plus some mix of further federal regulation of greenhouse gases and state and local initiatives. So what happens if BBB, which currently has the support of just 48 senators, fails to pass and leaves the IIJA by itself as primary federal climate policy?

"That's the million-dollar question, isn't it?" Higman says. "The infrastructure act is a down payment on new technologies and climate commitments. Tax incentives are certainly also needed to meet the near-term goal of 50% reduction in emissions by 2030. It's up in the air."

*

Coming December 28: Part Four of our “Build What Better?” series analyzes the rising influence of environmental and social-justice concerns on public projects, and asks: What do municipal bonds owe the world?