Bill Courtright pleaded guilty to three felony pay-to-play public corruption charges in a Pennsylvania federal court Tuesday, one day after resigning as Scranton's mayor.

The charges were criminal conspiracy, attempting to obstruct commerce by extortion and bribery concerning programs receiving federal funds.

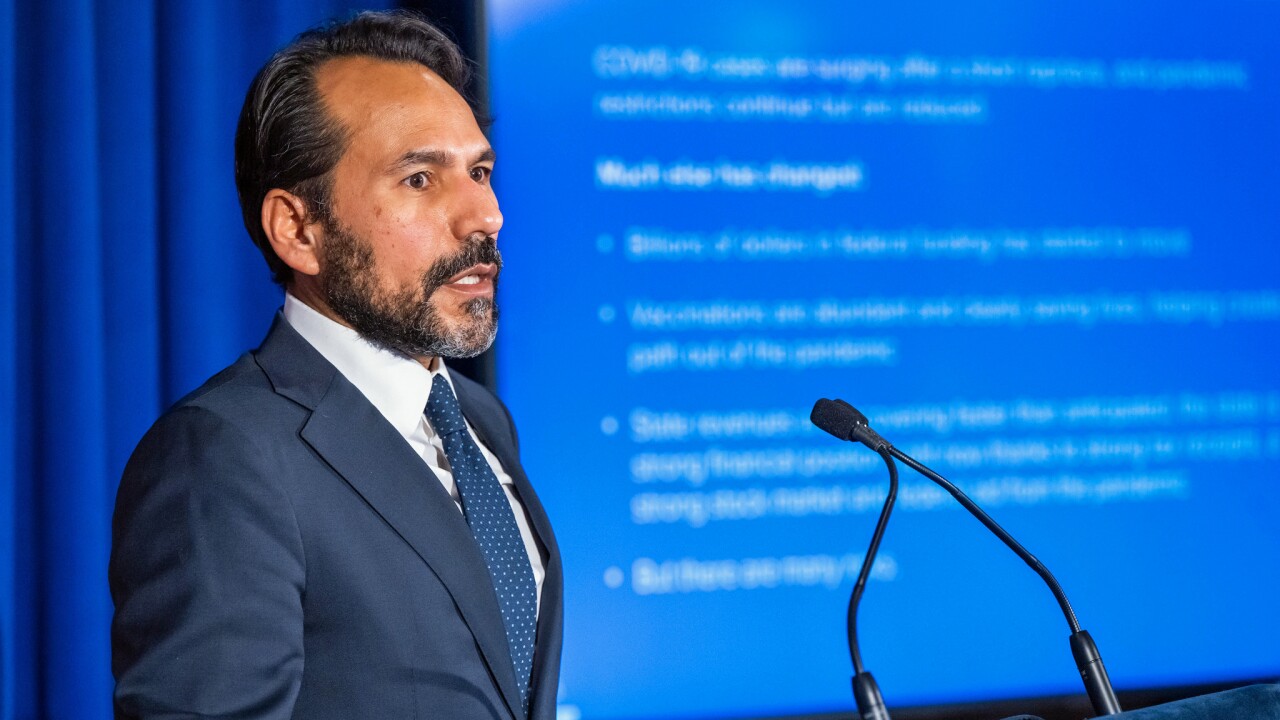

U.S. Attorney David Freed of the Middle District of Pennsylvania, meanwhile, said the investigation is ongoing.

"I am speaking now, to every public official within the sound of my voice. If it is not enough for you, get out now," Freed told reporters in Scranton. "Using public office for personal financial gain is a crime, plain and simple. People here have seen too much of it."

The FBI, Pennsylvania State Police and the Internal Revenue Service have launched a task force to tackle public corruption in northeast Pennsylvania.

Courtright, 61, surrendered at the Herman T. Schneebeli Federal Building in Williamstown, 85 miles away, where the assigned judge, Christopher Conner, is presiding over a separate trial.

Courtright, a Democrat and former City Council member and tax collector, was elected mayor of Scranton in 2013 and re-elected mayor four years later.

He resigned in a one-sentence letter to the City Council on Monday. By city bylaws, council President Pat Rogan will be acting mayor for 30 days until the council appoints someone to fill out Courtright's term.

Gary St. Fleur, a former independent mayoral candidate and founder of the civic organization Save Scranton, painted a bleak picture for the city, which has operated under Pennsylvania's oversight program for distressed communities since 1992.

"The city is bleeding money and borrowing in what amounts to a payday loan. Now you have the selling of public assets, extortion, conspiracy and bribery," said St. Fleur, who led a taxpayer group's successful lawsuit that alleged Scranton with collecting taxes beyond the state-imposed legal limit.

Courtright was released after the hearing without bail. He faces a maximum sentence of 35 years at sentencing, scheduled for Nov. 14.

He would not speak with reporters en route to the courthouse.

"Mr. Courtright wants to put this behind him for the sake of his family,” said his attorney, Paul Walker, according to the Morning Call of Allentown. “It has taken a terrible toll on his family.”

A two-year FBI probe started in 2017 and included a raid on Courtright's home and City Hall office in January. Freed said investigators found a safe in Courtright's home basement that included $30,000, some of it in FBI-marked bills.

Prosecutors, who said Courtright was secretly recorded in conversations with city employees and city vendors working with the FBI, alleged that Courtright took payments from at least 10 businesses contracted with the city or looking for work.

"At that time, Courtright expressed concern that [one] person might be working with 'the feds,'" Freed said. "Courtright suggested the cash should be given to an intermediary, who would then give it to Courtright.

"Regarding to that person, Courtright said, 'Is he going to sing if he ever gets nailed?' After being assured that Person Number One would not implicate Courtright, he said, 'If they say you gave it to me, I'm going to say you never gave me a dime.'"

Assistant U.S. Attorneys Michael Consiglio, Michelle Olshefski and William Houser are prosecuting the case.

“Bill Courtright used the city of Scranton,” said Michael Harpster, special agent in charge of the FBI's Philadelphia Division. “He traded on his office in exchange for money and other valuable favors. He wielded his official powers for his own benefit, when he should have been focused on that of his community."

Courtright's troubles cast yet another cloud over a city that had been looking to exit state oversight this year from the state-sponsored Act 47 workout program for distressed communities.

Scranton, the 77,000-population seat of Lackawanna County in northeast Pennsylvania, has struggled with chronic budget imbalance and unfunded pension liability. Its credibility in capital markets plummeted in 2012 when it missed a bond payment to the local parking authority amid a political dispute.

The city's bonds are junk. S&P Global Ratings, the only agency that rates the city, assigns its BB-plus rating, one level into speculative grade. S&P in August 2017 upgraded the city from BB after it sold its sewer system and earmarked a majority of sale proceeds to retire more than $40 million in high-coupon debt.

Corruption scandals have clouded Pennsylvania municipalities in recent years.

"My contention is that these places — Harrisburg, Reading, Scranton and Allentown — are easy prey for criminal organizations," St. Fleur said.

Federal juries convicted Ed Pawlowski and Vaughn Spencer, the former mayors of Allentown and Reading, respectively, in pay-to-play corruption trials in 2018.

Pawlowski in October received a 15-year sentence for his conviction in a pay-to-play corruption scheme. The federal case was part of an overall corruption sweep in Pennsylvania that included Reading, 40 miles southwest of Allentown. Spencer received an eight-year sentence in April.

Steven Reed, mayor of capital city Harrisburg from 1982 to 2010, pleaded guilty in 2017 to 20 counts of theft by receiving stolen property, Wild West artifacts. He received two years' probation but no prison time.

"Pennsylvania mayors and municipal managers are somewhat buffered and insulated from the audits that are required by state and federal mandates," said David Fiorenza, a Villanova School of Business professor and former chief financial officer of Radnor Township, outside Philadelphia.

"They do not see the scrutiny a finance officer does and more controls should be set by the independent auditors of the city and municipalities in Pennsylvania."

The commonwealth, Fiorenza said, has taken some steps to include the mayors in the audit from an ethics perspective but not from a financial one.

All elected and appointed officials, he said, do complete an annual financial statement to disclose certain financial details of their lives, "but a lot of time elapsed between the completion of the paperwork and the review by the commonwealth."

Anthony Sabino, a Mineola, New York, defense attorney and St. John's University law professor, dismissed any connection between the corruption cases.

"There is nothing wrong with the drinking water in Pennsylvania, and anyone who connects these recent scandals with some epidemic of corruption in the Keystone State is just plain wrong," he said.

"The connections — plural— are these: Combine basic human greed with opportunity, lax internal controls and bureaucracy, and it's an invitation to steal. You cannot remedy the first, but everything else on the list can and should be changed."