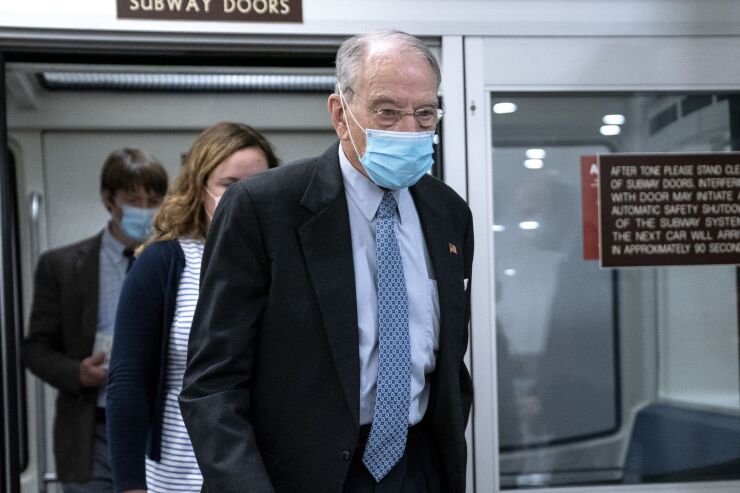

Senate Finance Chairman Chuck Grassley called on incoming President Joe Biden to make permanent lower tax rates created in 2017, which has curtailed muni demand.

In a press release last week, the Iowa Republican asked Biden to commit to making the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act permanent, including lower tax rates for businesses and individuals.

“President-elect Biden ran on rebuilding the nation’s economy that’s been devastated by the pandemic,” Grassley wrote. “Families, small businesses and the American economy can’t recover, rehire or grow to their full potential with higher taxes on the horizon. It’s now President-elect Biden’s responsibility to make sure this doesn’t happen on his watch.”

Biden seems unlikely to bite. Biden himself has called for increasing the corporate income tax to 28% from 21%. Also, a pair of Senate runoffs in Georgia in early January leaves the Senate majority undecided. Two seats are up for grabs and Democrats would gain control of the Senate if they won both.

Higher corporate tax rates tend to drive up demand for munis, especially among banks and property and casualty insurers, according to an Alliance Bernstein October report.

Biden also proposed an increase in the top personal income tax rate to 39.6% from 37%. That tax hike would also increase demand for muni bonds, especially among wealthier earners, the asset management company said.

Grassley hopes to maintain many aspects of the TCJA, including the prohibition on tax-exempt advance refunding, his staff said. Muni advocates want tax-exempt advance refunding reinstated, which could be possible in a Biden administration. House Democrats passed an infrastructure bill over the summer that would permanently reinstate tax-exempt advance refunding among other measures.

Grassley’s ask seems unlikely given Sen. Mike Crapo, R-Idaho, is

The TCJA reallocated demand for munis away from people making $100,000 or less a year in favor of the highest income bracket, said Matt Fabian, partner at Municipal Market Analytics.

“That itself is a spread tightener because wealthier investors take additional risks in the types of bonds that they buy,” Fabian said. “If the tax code were to start 2021 exactly where it was in 2017 instead of neutralizing the TCJA, aggregate individual demand might be the same, but the nature of muni demand would skew towards lower-income folks.”

That is because the TCJA raised the standard deduction for filers, in turn reducing their interest in muni bonds, Fabian added.

If the tax code were to be restored immediately to 2017 status, credit spreads would likely widen and demand would stay the same. However, times have changed with an increase in exchange-traded fund accounts and mutual funds caused spreads to tighten, Fabian said.

“The kinds of accounts that people used three years ago to buy munis are just not around anymore,” Fabian said.

The restoration of tax-exempt advance refunding is likely to see a comeback.

“Seeing what’s happened this year with 30% being taxable and much of that reflecting issuers using advance refunding and being forced to use taxable bonds because of the TCJA,” Fabian said. “There could have been substantial savings to state and local governments if they had access to the tax exemption this year.”