A spiraling repair bill and a widening lead-paint scandal at the New York City Housing Authority have prompted investigations and calls for an overhaul of the agency.

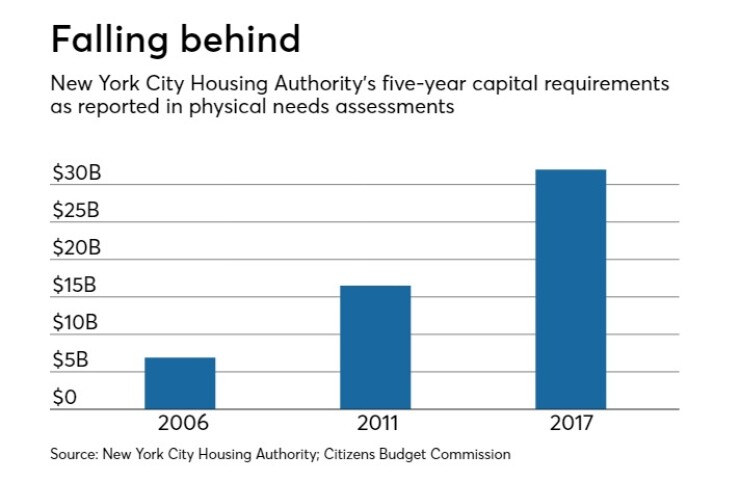

The watchdog Citizens Budget Commission on Tuesday, one day after NYCHA estimated its five-year capital-needs backlog at $31.8 billion, said that without dramatic change, 90% of NYCHA units by 2027 could be too cost-ineffective to repair.

City Comptroller Scott Stringer, meanwhile, has launched an investigation into city procedures for troubleshooting lead poisoning hazards.

Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration has acknowledged a lack of follow-up by health officials on as many as 820 children in city housing projects who tested for elevated levels of lead.

Stringer said his probe would extend “from the Department of Health to NYCHA to City Hall.”

NYCHA is already under a U.S. District Court consent decree that includes a federal monitor and requires the city to allocate $1 billion over four years to improve building conditions.

“Neither the decree nor other proposals go far enough,” CBC president Carol Kellermann said of recommendations that range from controls on NYCHA management to greater funding.

NYCHA’s long-overdue capital needs

“The challenges are staggering,” the assessment said.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development encourages public housing authorities to assess the capital needs of their housing units at least once every five years. Authorities use the assessment to prioritize capital investments, develop long-range capital plans and make funding requests to state and federal governments.

NYCHA's 404,000 residents constitute about 5% of the city's population. If it were a municipality, it would rank as the 47th-largest U.S. city. The authority houses more people than the populations of Cleveland or New Orleans, while within a much smaller footprint.

The CBC, in a

CBC recommended fully integrating NYCHA into the city's 10-year affordable housing strategy, including shifting $1 billion in city capital funds to the authority; transitioning NYCHA to an affordable housing steward that manages fewer buildings by rapidly accelerating public-private partnerships and selling selected units.

In addition, the commission called for decentralized property management, overhauling collective bargaining and staffing arrangements, increasing use of private maintenance contracts and use of design-build procurement.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo in March extended limited use of design-build for NYCHA and other city agencies. The state legislature would have to approve broader city use.

The CBC attributed the decline of NYCHA’s stock to other factors besides age. It cited a decline in federal funding and limited city and state support; inefficiencies due to restrictive federally mandated procurement rules and high-cost operations; and limited innovation, including P3s and air rights, both of which exist in the 10-year strategic plan called Next Generation NYCHA.

De Blasio on Monday defended his administration’s efforts.

“The city has seen a 90% reduction in lead paint poisoning, or lead poisoning I should say overall in the last decade. We are actually one of the national leaders on this,” the mayor said. “We’ve seen the numbers go down in NYCHA and in private housing but we take every case seriously.”

According to the mayor, city officials, going back to predecessor Michael Bloomberg's administration, had used an older, less stringent standard than the Centers for Disease Control had specified.

Stanley Brezenoff, former chief at the city’s Health + Hospitals unit, is NYCHA’s interim head.