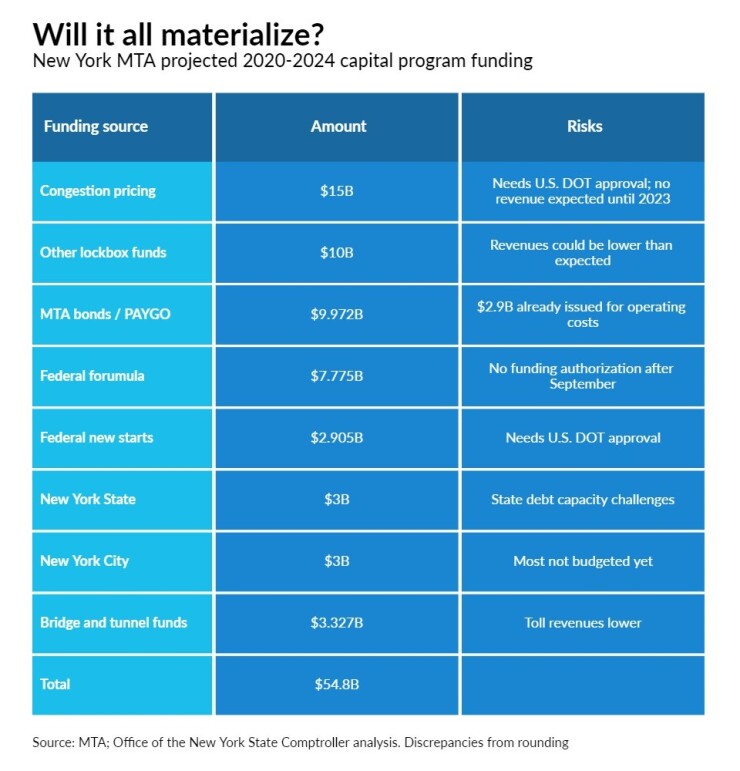

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority lacks the resources to fully fund its five-year, $54.8 billion capital program for 2020 to 2024, New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli said.

DiNapoli, citing a $2.9 billion hole, said in Tuesday’s

“The MTA’s mounting debts and devastated revenue make it unlikely that it can afford all the work it planned. The numbers just don’t add up,” DiNapoli said.

According to MTA spokesman Aaron Donovan, the authority is getting capital projects done faster and less expensively through its new construction and development unit "that is cutting past forms of red tape, using new contracting methods that create incentives for contractors to cut schedules and bundling projects, among other innovations."

Donovan added: "We have worked safely to continue the capital program through the pandemic, bringing real progress on station accessibility, subway resignalling, major marquee projects like the L project and [Long Island Rail Road] third track, and projects to bring the system into a state of good repair.”

New variables include the MTA's issuance of Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority payroll mobility tax notes -- a new credit -- and the Federal Reserve's Municipal Liquidity Facility, a program the MTA tapped last year it dissolved.

Until the MTA determines how it will close out-year deficits, it is unclear how much it would issue in bonds, if any, to meet its $9.8 billion commitment to funding the 2020-2024 capital program.

On Tuesday, the MTA was to sell $1.3 billion of TBTA payroll mobility tax senior lien bonds, a structure that got it AA-plus ratings from S&P Global Ratings, Fitch Ratings and Kroll Bond Rating Agency, a big bump up from the MTA's main transportation revenue bond credit, which carries ratings between BBB-plus and AA. Kroll’s outlook is stable, the others are negative.

The MTA, one of the largest municipal bond issuers, has $49.4 billion of debt outstanding including Hudson Yards Rail Trust obligations, according to finance committee documents released in advance of Wednesday’s board meeting.

Its long-term debt more than tripled between 2000 and 2020, according to DiNapoli.

Even before the pandemic took hold in March 2020, the MTA was wrestling with budget imbalance, missed capital commitment goals, capital funding risks and escalating debt.

Since the pandemic, ridership has plummeted amid shutdowns, stay-at-home work mandates and a spike in crime. Despite a recent ridership bump, total MetroCard swipes are still down nearly two-thirds from pre-pandemic levels. The MTA released its own survey last week that showed 72% of subway riders were “very concerned” with crime and harassment.

“The debt profile reflects these challenges and is cause for increasing concern,” DiNapoli said.

The MTA, which operates New York City’s subway-and-bus system, two commuter rail lines and seven interborough bridges and tunnels, was able to balance its 2020 and 2021 budgets with emergency federal aid and funds that had been earmarked for capital.

Including the recent $6.5 billion injection through the American Rescue Plan, the authority has received $14.5 billion from Washington over the past year.

Capital program uncertainties include the need for federal approval of congestion pricing for Manhattan’s central business district. The MTA has projected $15 billion through bonding.

Congestion pricing will charge fees to vehicles entering and remaining in Manhattan at 60th Street or below. The federal government has advised the MTA that it should conduct an environmental assessment, which consumes less time than a full environmental impact statement.

The MTA expects final approval later this year, yet does not expect to receive revenue from congestion pricing at least until 2023.

“We're carrying 90 percent of the cars and trucks that we carried pre-pandemic, so the need for congestion pricing, and the urgency, is clear,” MTA Chairman Patrick Foye told reporters recently. “It’s 30 percent of our capital plan, that's an astounding number. There should be a robust discussion on exemptions, but we have to move forward with congestion pricing.”

Goldman Sachs was the lead bookrunner for Tuesday’s sale of payroll mobility tax senior lien bonds in two series. Payroll mobility tax receipts secured the bonds.

The tax, which New York State provided as part of an aid package in 2009, is imposed on employers and individuals engaging in business inside the MTA’s district, which consists of New York City and seven surrounding counties.

“We consider the broad tax base, inclusive of suburbs and exurban areas around New York City, to be a key credit strength, particularly given the uncertainty around city life per the pandemic,” research firm CreditSights said in a commentary.

CreditSights called the new credit high-grade.

“Over time, we expect PMT bonds will be less volatile than TBTA general revenue or MTA transportation revenue bonds.”