After years of underfunding and inattention, New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority is playing catch-up on accessibility.

The initiative, part of the MTA’s overall modernization thrust, includes the hiring of Alex Elegudin as New York City Transit’s first executive for accessibility. He began June 25 and reports directly to NYC Transit President Andy Byford.

Elegudin’s job, Byford said after a recent MTA board meeting, is to "obsess about [accessibility] and to keep me focused on that key item … so his job across all of my departments, across all of the projects, is to drive forward those initiatives in consultation with the accessibility advocacy community.”

The state-run MTA, a large municipal issuer with roughly $38 billion in debt, operates the city’s mass transit system, plus several intraborough tunnels and bridges.

According to the MTA, only 118 of its 472 subway stations, or 25%, are wheelchair accessible, with 25 more in progress to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act. An ADA-compliant station must be fully navigable from the street to the platform for wheelchair users.

The authority has earmarked nearly $5 billion to make subway stations accessible, including $1.4 billion in its 2015-19 MTA capital program. That program also includes $479 million to replace 42 existing elevators and 27 escalators. Future capital programs will include funding for additional stations.

Improving accessibility is one of four key components of Byford’s “

The overall price tag for Fast Forward is still an open question, with some estimates ranging from $18 billion to $20 billion. Byford, when unveiling the blueprint in May, implored MTA board members to advance their 2020 to 2024 capital program, which a state review panel must approve.

Additional funding would need the backing of Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who controls the MTA.

“The governor interviewed me and hired me. I meet with the governor often, I speak with him regularly," Byford said. "The governor fully supports the Fast Forward plan, which we are extremely happy about."

Big-ticket expense items such as elevators take time. Elegudin, a 34-year-old who uses a wheelchair to get around, said the MTA can instantly move to restore confidence with a skeptical public, achieving what Byford likes to call “quick wins.”

“This was part of the interview process, actually,” Byford said. “We did talk to candidates about what they saw as potential quick wins.”

Communication is foremost, Elegudin said in an interview at MTA headquarters in lower Manhattan.

“If customers know better if there are issues, or things are happening in the system, they can plan their day. The worst thing that can happen to you as a person with disabilities is if you can get to an elevator, or you get to something, and it’s not working. If I knew it wasn’t, there are alternatives.”

While a college undergraduate, Elegudin in 2003 suffered a spinal-cord injury in a deer-related car accident. After his injury, Elegudin continued his studies, receiving a degree from Hofstra University Law School, passing the bar exam and becoming a patent attorney while also pursuing a career as an accessibility advocate.

In 2011, Elegudin co-founded the nonprofit

Elegudin in 2015 became the accessibility program manager at the New York City Taxi & Limousine Commission.

According to Elegudin, the parameters for disability are much wider than previously, while greater overall awareness has helped build momentum.

“One of the biggest changes is cultural,” he said.

The MTA also has a new express bus in the works that will feature a wheelchair ramp instead of a lift, with dedicated seating. The authority displayed the bus across the street from its headquarters last month.

Additionally, as part of mitigation for the expected L subway line shutdown to begin in April, the MTA is planning new elevators for the F and L lines at 14th Street in Manhattan. That will partially settle a suit Manhattan community residents and disability advocates filed against the MTA over the shutdown, which the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York joined in March.

Authority efforts to streamline procurements could also pay accessibility dividends.

“By taking a ‘get it done and let’s make it happen’ attitude to accessibility as opposed to fighting with advocates for many years and figuring out what happens in legal battles, it just shows a lot about where the MTA is looking to go, and their attitude toward making this issue a priority,” Elegudin said.

“But ultimately I do think that riders do have to wait to see something before they really believe in it, and we understand that, and want to deliver that,” Elegudin said. “There are priorities across the system. I mean, Access-a-Ride – paratransit – has a ways to improve.”

Byford maintains the MTA can win credibility points through immediate steps.

“I think there’s a whole raft of activities that can make improvements in the short term. Some of those are already underway,” he said.

“I would say quick wins include making elevators more available – the existing fleet of elevators, make sure they’re more reliable – that where an elevator does go down, that where an elevator does go out of service for whatever reason, that we’re exponentially better at keeping customers informed, [in] real time via members of staff but also through better apps and better information put onto those apps.”

The authority on Monday launched a test version of “MyMTA,” a

In connection with the new app, the MTA has begun a process of data improvement and modernization, building an infrastructure that includes new trip planning engines and enhanced monitoring.

Additionally, said Byford, the authority is ramping up sensitivity training for its employees and coaching its bus staff to check ramps and lifts more thoroughly before making their daily rounds. The authority has also increased pay for elevator mechanics to better compete against the private sector.

“It’s a good idea, and not just for people with disabilities,” said Nicole Gelinas, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. “You have parents with young children and people with suitcases.

“The question is, where does it fit in with other priorities, such as signals and mitigating delays? It’s a sound idea, but the details are in the execution.”

Transportation think tank

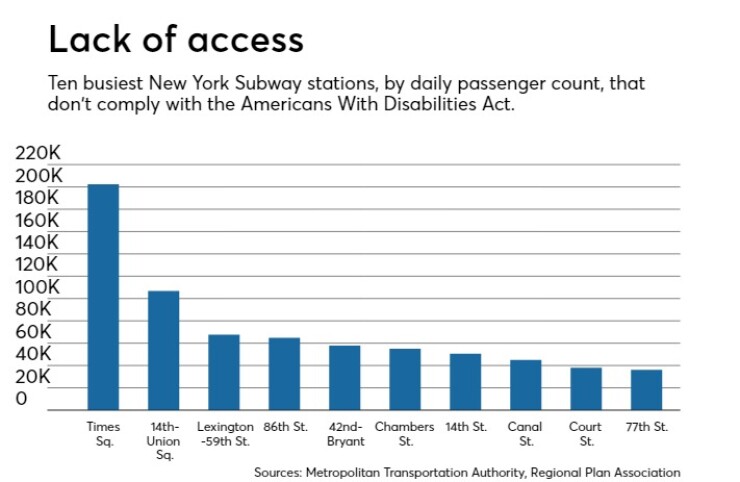

The top 30 non-accessible stations and/or complexes, based on weekday ridership, are in Manhattan, downtown Brooklyn and Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood. The most crowded are Times Square, which serves 11 lines; and 14th Street-Union Square and the Lexington Avenue corridor, which serve seven and six lines, respectively.

RPA, in its report on the system overall headlined “Save Our Subways,” called for moves beyond making all 472 stations ADA-compliant.

“Improving the mobility of these users will help everyone else as well,” said the report. “It will remove the elderly or disabled straphangers that struggle to make it up the stairs or those dragging their suitcases — all which act to impede the flow of patrons.”

Interventions should include removing or pruning columns whenever possible, and rebuilding major hubs such as Union Square and Herald Square to create large, column-free fare control areas and wider walkways.

“Making the subway less confusing and more open, with clear sightlines, will reduce crowding [and anxiety] and make the system easier to navigate,” said RPA.