When is a triple-B bond safer than a triple-A? The answer, based on historical default rates, is when the triple-B is a municipal bond and the other is a corporate security.

The ratings divergence isn't only a consideration for investors trying to choose between munis and corporates. On June 15 a Dodd-Frank Act rule goes into effect that requires rating agencies to adopt procedures designed so credit ratings weigh default risk "in a manner that is consistent" for all rated obligors and securities.

The approaching deadline "creates an imperative to get everything lined up," said Mark Adelson, a former chief credit officer at Standard & Poor's.

S&P and Moody's spokesmen said they were taking the rule seriously.

"We've been making preparations for this for years," a Moody's spokesman said. "Most of the preparations are pretty much done. We've already made most of the changes."

In the long run, the new rule "will only help the municipal upgrade trend," said Municipal Market Analytics managing director Matt Fabian. "Historically municipal ratings have been too low and have exaggerated the risk of default."

An attorney with experience in SEC regulatory compliance, speaking anonymously, said he was skeptical the current ratings for munis and corporates would be acceptable to the SEC.

"There is no way that is a uniform scale, and all it really takes to get the ball rolling is a complaint to the SEC that points out that disparity in default statistics," he said.

As for the investor implications, since BBB munis offer higher yields than AAA corporates as well as a tax exemption that the corporates lack, some may ask: why should anyone or any entity own corporates?

Default Rates and Yields

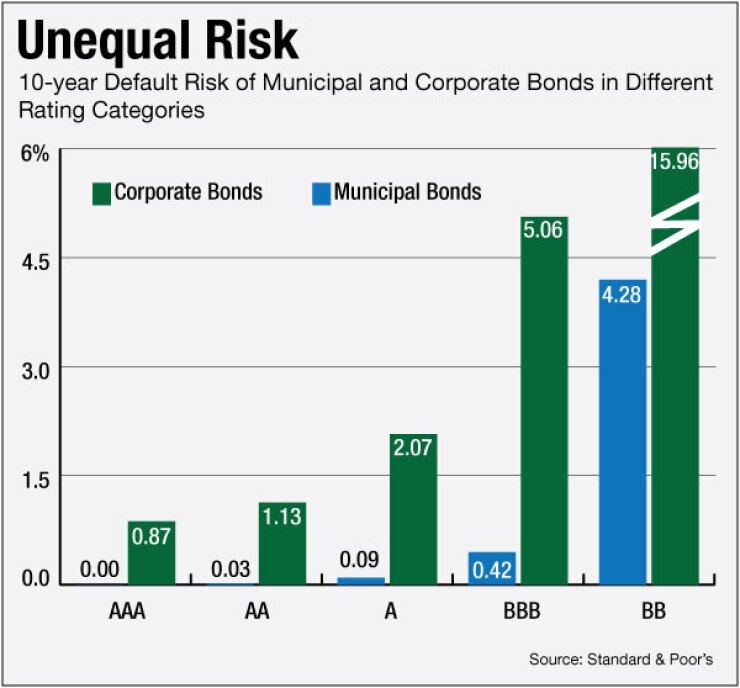

Studies published by Moody's Investors Service and Standard & Poor's show that the default rates of munis 10 years after being rated BBB are lower than the default rates of corporates 10 years after being rated AAA.

According to a Moody's report "US Municipal Bond Defaults and Recoveries, 1970-2013," the 10-year cumulative default rate for munis rated Baa1, Baa2 or Baa3 was 0.32%. According to the same study, the rate for Aaa corporates was 0.49%.

S&P Wednesday released its latest default report. The study by analyst Lawrence Witte found that in the 10 years after municipal bonds were rated BBB-plus, BBB, or BBB-minus, 0.42% defaulted. A March 2014 study by S&P managing director Diane Vazza and several others found that in the 10 years after corporate bonds were rated AAA, 0.87% defaulted.

If that history provides guidance, then Chicago (Baa2) is a safer investment over the long-term than Microsoft (Aaa). Moody's dropped the city's general obligation rating in February, citing the city's high levels of debt and pension obligations and expected growth in unfunded pension liabilities. S&P rates Chicago A-plus.

Even with lower default rates, investors in the munis are getting higher yields. On April 27, according to S&P Global Fixed Income, the average yield for a triple-A corporate bond with a 10 year maturity was 2.69%.

By comparison, according to Municipal Market Data on that date the average yield for a BBB general obligation municipal bond with a 10-year maturity was 2.94% and for a BBB taxable municipal bond with this maturity it was 4.13%. The BBB-rated muni yields are the average for BBB-plus, BBB, BBB-minus, Baa1, Baa2, and Baa3 bonds.

The interest of the GO would be tax-free while the interest from the corporate would be taxable.

After federal taxes, for those in the highest federal tax bracket, a corporate 10-year AAA bond bought on April 27 would have yielded 1.51% and the taxable muni would have yielded 2.31%. For those in a more moderate federal 25% tax bracket, these same bonds would have yielded 2.02% and 3.10% after federal taxes, respectively. These after-tax yields take into account federal taxes but not state or local taxes, which would normally lower the effective yield further.

Triple-B category GO muni bonds have consistently had more yield than AAA corporates. One year ago the spread was 31 basis points, five years ago 43 basis points, and 10 years ago nine basis points. None of these spreads take into account the impact taxes have in lowering corporate bonds' effective yields.

At any given point on the rating scale, munis have far less history of default than do corporates. In the 10 years after being rated Aaa 0.00% of the munis defaulted, while 0.49% of corporates defaulted, according to Moody's. Ten years after being rated Baa1, Baa2, or Baa3, 0.32% of munis defaulted, while 4.61% of corporates defaulted. Finally, in the 10 years after being rated Ba1, Ba2, or Ba3, 3.53% of munis defaulted, but 19.27% of corporates defaulted.

The Differences' Origin and Significance

Given munis' apparent superiority over corporates in terms of both yield and safety, The Bond Buyer asked several investment firms about the wisdom of holding corporates instead of munis. Citi, JPMorgan, Franklin Templeton, OppenheimerFunds, and Bank of America Merrill Lynch declined to answer.

MMA's Fabian said munis were frequently less liquid and less transparent than corporates. As for the liquidity issue, many munis "lack price discovery or ready markets," he said. Corporate bonds "often have a homogenous security pledge while municipal deals are essentially bespoke financings requiring that investors fully read the documents to know what they own."

"Lenders will look past these problems with municipals only because the default rates are so low," Fabian said.

At Charles Schwab, managing director Rob Williams and director Collin Martin wrote in an email that the default studies looked backward not forward. The migration of ratings upward by Moody's and S&P in the munis space in recent years may make their default rates more closely compare to corporates in the future. "Still, we expect that the default rate, on average, for investment-grade munis should remain lower than the default rate on investment-grade corporates," they wrote.

The Schwab officials also said there are fewer high-yield munis to choose from, compared with the selection of corporates. For investors who want to buy higher-yield bonds, corporates offer a wider choice, they said.

Corporate bonds can also be a wise choice for investors who plan to put them into tax-deferred accounts, like 401(k)s, they said.

"While default and recovery statistics appear better for municipal than like-rated corporate debt, that is based on historical information," said Howard Cure, director of municipal research at Evercore Wealth Management. "We are in a new era where we can see more municipal defaults going forward."

Alexandra Lebenthal, chief executive officer of Lebenthal Holdings, said she assumed that most corporate bonds are held in tax-deferred accounts, and people generally want to spread their eggs around.

The default rates and returns "show why munis make more sense," she said.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission provision requiring comparability of ratings within an agency is paragraph (b)(3) of Rule 17g-8 on Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organizations.

In the final rule the SEC noted that the divergence between ratings' default rates at ratings agencies are not just between safer munis and riskier corporates. According to one study up to 2005, the five-year default rates of collateralized debt obligations at the lowest investment grade ratings from one ratings agency was about 10 times higher than the five-year default rates for corporate bonds, the SEC said.

The 2010 Dodd-Frank Act requires the SEC to examine each nationally recognized statistical rating organization once a year and issue an annual report summarizing the examination findings. The annual report to Congress is required by the Credit Rating Agency Reform Act of 2006.

In a December 2014 story on the SEC's increased demands on the ratings agencies, Moody's said in a statement to The Bond Buyer, "Moody's continues to enhance our policies and procedures in light of regulatory developments, and the SEC staff's findings and recommendations are helpful in that effort."

Ratings Agencies Respond

How the new rule affects ratings agencies' ratings remains to be seen.

In recent years both Moody's and S&P have engaged in recalibrations or applied new criteria to U.S. public finance, leading to broadly higher ratings for munis.

On average the changes were subtle. For example, in 2013 and 2014 S&P introduced a new local government rating criteria. This led to an approximately average 0.4 notch increase in the local government credits. Local government credits are 28% of all credits that S&P's U.S. Public Finance Group handles. So the changes to the local government rating criteria led to an average increase in ratings of about 0.1 notch across all the credits.

In 2010 Moody's did a recalibration of some of its municipal issuer ratings to address the category's comparative lack of risk at different rating levels. In categories closest to government, like general obligation and public water and sewer utility bonds, it raised ratings about one notch in the Aa category, two in the A category, and about three in the Baa category. Speculative grade ratings were left unchanged. For non-utility enterprise, public university, mass transit and a few other categories, Moody's raised the ratings by one notch around the Aa and A categories. It left ratings unchanged for several other categories like nonprofits and public electric power utility bonds.

Neither S&P nor Moody's provided details on the overall average shift in their ratings due to these broad-based rating shifts.

One reason the ratings agencies maintain different levels of credit risks for given ratings between munis and corporates is that, "if you call [all municipal bonds] AAA then one is not creating a lot of value," for the user of municipal ratings, said Adelson, the former S&P chief credit officer, who now is chief strategy officer at BondFactor.

In response to queries from The Bond Buyer about the divergent default histories at a given rating between munis and corporates, S&P and Moody's gave similar answers.

"Comparability of ratings across asset classes and geographies is one of Standard & Poor's main goals and one of the benefits of our global ratings scale," S&P said in an email. "To accomplish this goal, we've adjusted all of our ratings to a common set of stress scenarios and definitions, which are embedded in all of our criteria.

"Our criteria are subject to regular periodic review across sectors to provide additional transparency and comparability. These improvements are intended to help market participants understand our approach to assigning ratings, enhance the forward-looking nature of these ratings, and enable better comparisons across ratings."

Moody's vice president Al Medioli said, "This is why Moody's underwent its recalibration back in 2010, which put all our ratings on a single, universal scale." He added, "Muni default rates are rising although still very low, and recovery rates are now similar to corporates in recent bankruptcies."

Both S&P and Moody's have known that default risks of their ratings diverge between corporates and munis since at least the early 1990s, Adelson said. They have shifted their responses back and forth over time but have never gone beyond making small adjustments to the ratings, he said.