There is plenty of blame to go around for Puerto Rico's precarious financial position, which has become a major worry for many municipal market participants.

While analysts point to years of bad Puerto Rico government policies as primary cause of the commonwealth's debt problem, in which bond obligations ballooned while its economy stagnated, they also believe state-side investors and rating agencies bear some responsibility.

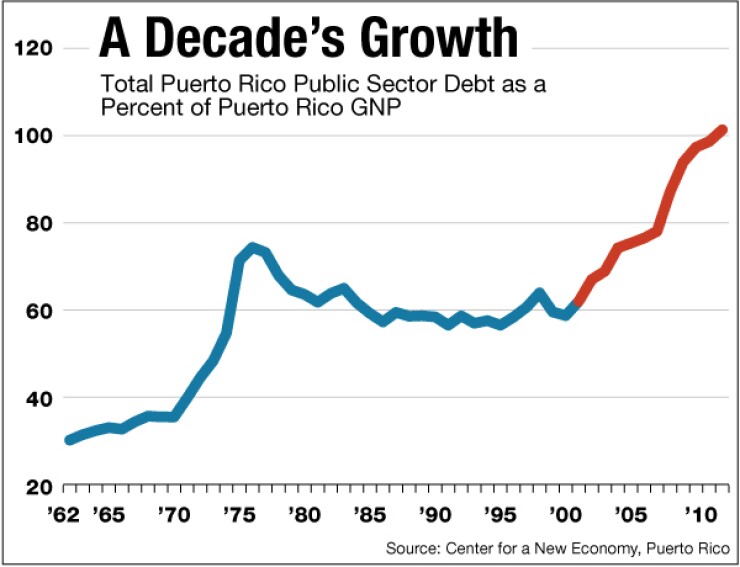

The ratio of total Puerto Rico government debt to the island's gross national product grew from about 30% in 1962 to about 74% in 1975, according to data compiled by the Center for a New Economy, a think tank in San Juan, the commonwealth's capital. It then decreased and stabilized around 60% until 2000.

Many economists would be comfortable with the 60% level, said Sergio Marxuach, the center's public policy director. But by 2012 the ratio had risen to 100.6%.

The $70 billion figure for 2012 includes all government debt in Puerto Rico, including local municipalities, public corporations, non-recourse and revenue-specific debt. Of the $70 billion, $44 billion (63% of GNP) is for the central government and the public corporations, including about $9.5 billion of Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority debt.

While analysts and the ratings agencies are united in saying that the size and growth of the debt has been a problem, some say the use of the debt has also been negative in various ways.

It would have been better if the debt had been used for strategic investments like building universities and dams, Center for a New Economy president Miguel Soto-Class said. Instead, in recent years it has been going to cover recurring costs like payroll.

In 1996 the United States government started a 10-year phase out of a tax incentive for United States companies to locate operations in Puerto Rico. The Puerto Rico government realized it needed a self-supporting economy and started to issue bonds to finance buildings, schools, roads, water and power infrastructure, said Municipal Market Advisors managing director Robert Donahue.

However, around 2000 the government started running operating deficits. The government started to look at bonds not only as a means of long-term investment but also as short-term stimulus and a way to finance deficits, he said.

The practice of financing deficits with bonds can be traced back to the 1980s, University of Puerto Rico professor Juan Lara said.

Starting around 2000 the government expanded a health care program for island residents, Mi Salud, and used debt to build a convention center and a sports arena, Marxuach said.

Since 2007 the government has also chosen to issue new debt to pay off old debt, assuring the further growth of debt, Donahue said.

Puerto Rico's weak economy has been a major contributor to its growing debt burden, several analysts said. Since 1972 the island's weak economy has led to an expansion of both public and private debt, said Jorge Duany, professor at Florida International University.

The economy has been particularly depressed since 2005, shrinking from that date to 2012 by 10% in inflation-adjusted gross national product.

Analysts also say political factors contributed to Puerto Rico's debt problem. The government has lacked budgetary discipline, said AllianceBernstein senior vice president Joseph Rosenblum.

Puerto Rico politics is dominated by the Popular Democratic Party and the New Progressive Party. Their main philosophical distinction is over statehood; the New Progressive Party is pro-statehood for Puerto Rico while the Popular Democratic Party supports the current status.

In practice, Soto-Class said, the parties have tried to outdo each other in building things in an unhealthy competition to gain votes.

Puerto Rico's nonvoting representative to Congress, Pedro Pierluisi, president of the New Progressive Party, said the island's debt problem is caused by its economic problems. These, in turn, are rooted in the island's territorial status, he said.

Puerto Rico is deprived of billions of dollars each year in federal grants and tax credits that would otherwise aid the economy, he said. Also, the federal government provides inferior services, including those for health care, public safety, and aid to the needy. The inferior services also harm the economy, Pierluisi said.

A final political cause of the debt problem is the island's ineffective tax system, two analysts said.

"Puerto Rico has had an ineffective tax system for decades," Lara said. "Even when the economy was growing (more than seven years ago), tax revenues did not grow at a healthy step. The deep, structural causes for this loss of buoyancy lie in the system's increasing complexity over time, the growing number of special exemptions and tax breaks for special interest groups, and the lax enforcement of tax laws that make it all too easy to avoid and evade taxes."

Marxuach agreed that in the last decade lax tax enforcement hurt government revenues.

Several analysts and observers also said that the municipal bond community and the ratings agencies also have a share of the blame.

"I think the rating agencies have a big part of the guilt for what's going on right now," Marxuach said. "For many years the rating agencies let the government go on a borrowing binge."

If the ratings agencies had lowered their ratings of Puerto Rico sooner, the government would have been pushed to address its debt problem when it was more manageable, he said.

However, it was not in their financial interests to lower Puerto Rico so they did not do so until recently, Marxuach said.

Janney Capital Markets managing director Alan Schankel agreed that the ratings agencies may have been too soft on Puerto Rico in the last decade and thus have some responsibility for the current situation. Part of the problem was that Puerto Rico's situation was not comparable to that of any of the other states or even other territories.

"Moody's has lowered Puerto Rico's credit rating twice over the last three years and it is currently rated Baa3 with a negative outlook, which reflects the commonwealth's weak economy, high debt levels, and high unfunded pension liabilities," said Moody's Investors Service managing director Bob Kurtter. "Moody's ratings reflect the independent, objective opinions of our analysts and are not influenced in any way by factors other than credit quality."

“The general trajectory of the credit has been down over a long period of time,” said Standard & Poor’s spokesman Ed Sweeney. “Our role is to reflect the credit performance of an issuance and our ratings on Puerto Rico have reflected it.”

“The idea that we let a government do something is not an accurate reflection of our role.” S&P’s role is just to observe, Sweeney continued. S&P has actively monitored the credit.

Fitch Ratings did not immediately respond to Marxuach’s and Schankel’s statements.

Municipal bond investors and mutual funds also have some of the blame, several said.

Bond investors have some responsibility. For too many, Puerto Rico bonds just represented high yields, Marxuach said. Supply and yield hungry state-specific mutual funds saw Puerto Rico bonds as "blank Scrabble tiles," Donahue said.

The commonwealth's triple tax exemption spurred stateside demand, lowering the yields that Puerto Rico would have to pay, and making bond sales attractive to Puerto Rico, Schankel and Soto-Class said.

The election of Luis Fortuño as Puerto Rico governor in late 2008 led to new government policies, several said. He was committed to balancing the budget and stimulating economic growth through shrinking the government.

As his term continued, Fortuño faced substantial economic, financial and political challenges, Donahue said. Fortuño lost his focus and became more politically motivated. The fiscal 2012 audit that showed government spending and deficit increasing and Fortuño's failure to implement a pension reform prior to a Dec. 31, 2012 deadline given to the rating agencies, showed his commitment to spending restraint diminished at the end of his term, Donahue said.

As for the current governor, Alejandro García Padilla, one has to give him credit for the pension reform, Marxuach said. However, García Padilla has not put out a thought-out strategy as to how to get out of the recession, Marxuach said.

For the last 10 years the government has said it would have a structurally balanced budget within two years and this has hurt its credibility, Marxuach said.

This year's Detroit bankruptcy had a big impact on the way the bond market views Puerto Rico, Marxuach said, out of proportion to the impact created by earlier municipal bankruptcies such as Jefferson County's.

"It's one thing to have a small county in Alabama go bankrupt and it's another thing to have a big city go bankrupt," Marxuach said.