DALLAS -- A lawsuit filed against the state of Michigan on behalf of 14 local municipalities this month seeks to correct what they contend is a miscalculation in state aid that has shortchanged them for two decades.

The governments are being shortchanged by as much as $4 billion a year, said Wayne State University School of Law professor John Mogk. He is the co-founder along with Eastpointe City Manager Steve Duchane of Taxpayers for Michigan Constitutional Government. The group filed the lawsuit with the Michigan Court of Appeals on Sept. 7th.

"We think we have a very credible argument that the calculations are completely wrong," says Mogk.

The lawsuit is based on the Michigan revenue sharing requirement that was established by the Headlee Amendment in 1978.

If the suit succeeds, local units of government stand to gain from an increased flow of state aid, but the increased burden could create a budget hole for the state.

The amendment requires that the state pay a minimum of 48.97% of monies raised through state taxes to local governments. It further stipulates what funding can and cannot be included in the calculation of the minimum percentage payment.

The Headlee Amendment says monies raised through tax shifts, monies paid to local governments to perform obligations of the state and monies paid to agencies that are not political subdivisions of the state cannot be included in the calculation of the minimum percentage payment.

The biggest drain has resulted from the tax shift created by the introduction of Proposal A in 1994.

The measure created a statewide property tax to fund schools, capped the rate at which revenue from the tax can increase, and prevents local school districts from asking voters for additional operations support through a property tax levy. It also increased the state sales tax by 2%, with revenue to go to the state's school aid funds.

The state, Mogk said, then counted the sales tax revenue sent to school districts against its Headlee Amendment obligations and reduced the other state revenues these local governments were previously receiving.

"The lawsuit is saying that the funding from the sales tax cannot then be counted in meeting the state's minimum state aid distribution requirement as outlined by Headlee," said Mogk. That tax shift amounts to about $2.5 billion in lost state revenue per year.

Michigan also spends $1 billion a year on charter schools, which the lawsuit argues are non-profit corporations, not political subdivisions of the state, and should therefore not be included in the calculation of the minimum mandatory payment. "Headlee says that the 48.7% is to be paid to political subdivisions of the state and charter schools cannot be added in the calculations," said Mogk.

"We concluded, depending upon the year, that [the state] is sharing around 40% or less," Mogk said. "That's what we're trying to correct."

The aim of the lawsuit is to correct the state's accounting practice which in turn would increase funds that flow to local governments.

Whether shortages would be refunded to local governments and how much would be up to the discretion of the court. To the extent that there is any interest from the court in doing that, Mogk said there is a limitation of either one or two years of state aid reimbursements that limits the damages the state is on the hook for.

The state is reviewing the complaint, "but it's important to note that these calculations have been consistently applied over time," said Kurt Weiss, a spokesman for Gov. Rick Snyder's budget office.

"The Office of Financial Management within the State Budget Office works hard each year to properly identify expenditures to determine the amount of state spending that goes to the aid of local governments," said Weiss. "Those expenditures are in turn submitted to the Office of Auditor General for validation to ensure the calculations are accurate. This is a methodology that has been applied consistently since the passage of Proposal A."

Although the state is beginning to increase revenue sharing, it's marginal relative to the $6 billion in cuts the state made between 2000 and 2013. The $1.2 billion in revenue-sharing payments Michigan will distribute to local governments in 2016 is down from nearly $1.6 billion in 2001.

"A major component of the state of Michigan's credit strength in recent years has been its ability to push costs down to, and pull revenues up from, its local governments," said Matt Fabian, a municipal bond analyst at Municipal Market Analytics. "Detroit's bankruptcy was catalyzed, in part, by state aid reductions."

Fabian said that if successful, the litigation based on Headlee could hit Michigan twice, first by creating a potentially large payable and near-term budget gap and second by more clearly limiting what additional resources the state might pull from its localities in the future.

And to the extent the municipalities prevail in the lawsuit, the impact could be muted, Fabian said. The state may just reduce overall state aid to its governments or increase unfunded mandates to protect its own finances.

"This means a minimal effective impact on the state and local governments, generally," said Fabian.

Local governments that belong to Taxpayers for Michigan Constitutional Government include Eastpointe, Roseville, Warren, Center Line, Mount Clemens, Clinton Township, Utica, Hazel Park, Harper Woods, Grosse Pointe Woods and the Village of Grosse Pointe Shores.

Eastpointe, for example, has lost an estimated $13.7 million cumulatively, according to Duchane. That funding shortage led to the city taking unusual measures to pay for essential services the city would have otherwise not been able to afford.

Homeowners in Eastpointe and Hazel Park last year approved a 20-year, 14-mill property tax to cover the cost of fire and rescue service. The measure allows the two financially strapped cities to form a regional services authority to provide public safety services.

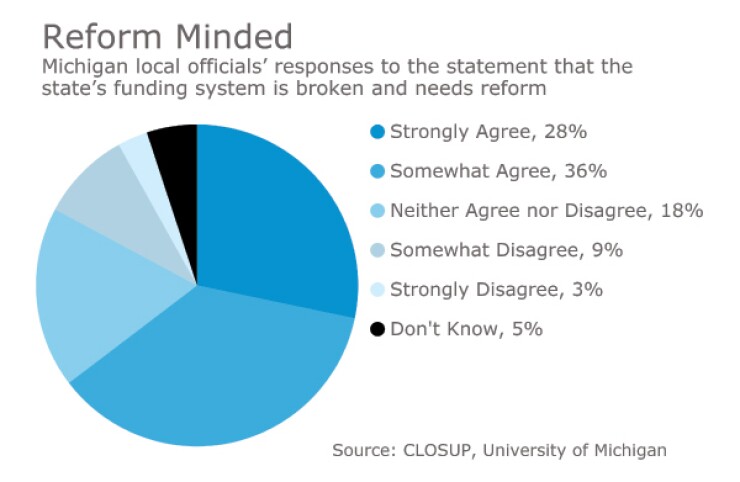

A recent University of Michigan Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy survey of all Michigan counties, cities, townships and villages found that nearly two-thirds of Michigan's local leaders believe that the state's system of funding local government is broken and in dire need of reform.

That CLOSUP survey is conducted twice yearly, with a 70% response rate.

Wayne County, home to Harper Woods, Grosse Pointe Woods and the Village of Grosse Pointe Shores, recently eliminated a nearly $100 million accumulated deficit and a yearly structural deficit of approximately $52 million.

In March, the county said it trimmed nearly $50 million in spending, achieved with elimination or modification of retirement benefits, a contraction of payroll, and other operating efficiencies.

The county, because of its financial distress, is operating under a consent agreement with the state. It is currently looking to end the consent agreement.

Wayne County Executive Warren Evans in his March State of the County address said Wayne's problems highlight a larger fundamental problem shared with Michigan's 43 cities and townships and that is "[management] of their financial affairs under a broken system of local government financing."

Evans has since undertaken the Investing in Michigan Communities: Finding Fair Funding for Strong, Successful Communities initiative, which is a statewide tour aimed at identifying viable solutions to Michigan's broken model for funding local governments.

"It doesn't matter where we go in the state – we are hearing over and over how the current funding system is failing Michigan communities," said Evans. "There is a growing consensus that we need more local control, reduced reliance on property taxes, and a larger share of state revenues to be returned to local communities."

The state was successful in another recent legal battle tied to its unpopular emergency manager law, Michigan's system of dealing with distressed local governments. On September 12 the U.S. Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals unanimously upheld the controversial law and ruled that it does not violate voting rights provisions in the Constitution, and it does not discriminate based on race.