Ramifications from the Long Island Rail Road’s so-called third track expansion — long in the making -- extend far beyond the commuters the project intends to serve.

Its effect on Long Island’s economy, its role in regional mass transit and the ability of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority to execute public-private partnerships and effectively manage a capital megaproject are on the radar.

On Dec. 13, the MTA board approved $2.6 billion for a design-build contract to expand the Long Island Rail Road’s east-west main line through a 9.8-mile-long third set of tracks from Floral Park to Hicksville.

“I really hope this ushers in a new era of looking at the entire region’s transportation as a region,” said William Henderson, executive director of the Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA.

The project is about 70 years in the making, stalled largely because of residential concerns on suburban Long Island.

Henderson recalled the chairman of a PCAC commuter council -- a project advocate -- needing a police escort to his car after speaking in favor of it at a public meeting.

“It hasn’t always been easy,” said Henderson. “Getting to yes is a really big deal.”

A 2014 Rauch Foundation-Long Island Index

Steven Bellone, executive of Suffolk County on eastern Long Island, trumpeted the project before the MTA's joint LIRR and Metro-North Railroad committee.

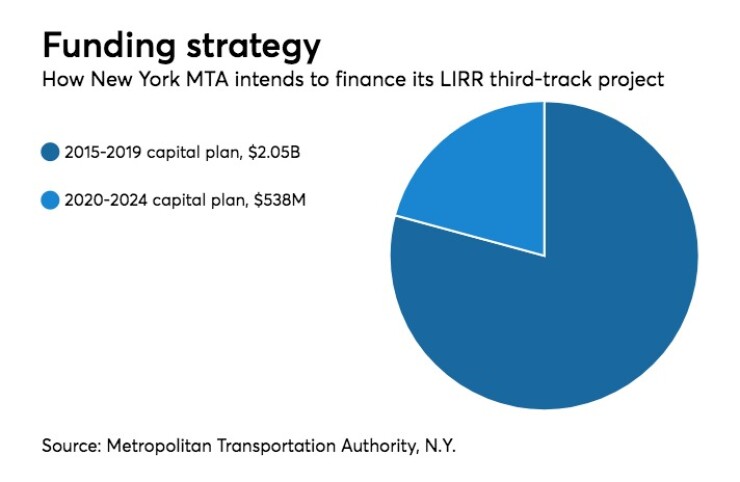

The estimated cost is already up from the initial $1.5 billion of two years ago. The new estimate includes $800 million for contingencies, insurance, acquisition of non-residential property and other variables, say MTA officials. The authority intends to fund $2.05 billion from the 2015 to 2019 capital program, with the remaining $538 million from the 2020 to 2024 plan.

3rd Track Constructors, a consortium that includes Dragados USA Inc., John P. Picone Inc., Halmar International LLC and CCA Civil Inc., submitted the winning bid. Stantec is the lead designer while Rubenstein Associates will lead the community outreach team.

“They were very innovative in their approach and they were comprehensive as well,” said LIRR executive vice president Elisa Picca. LIRR is an MTA unit.

Picca and MTA chief development officer Janno Lieber cited economic development benefits for the island.

“This project is going to unlock the full potential of East Side access, double track, the Jamaica station reconstruction and other major investments,” said Lieber. Double track involves a second set of tracks along the now single-track 18-mile corridor between Farmingdale and Ronkonkoma.

The third track project, to be built within LIRR rights-of-way, will include the elimination of seven dangerous street-level grade crossings – 24 people have died at those crossings since 1980 and 20 bridge strikes have occurred since 2016, according to Lieber. Also on the to-do list are upgrades, including compliance under the Americans with Disabilities Act, to six stations; the raising of seven bridges, mostly through a “roll-in” process after separate construction; and state-of-good-repair work on signals, switches and substations.

Also in the works are four parking garages through public-private partnerships.

To mitigate the community objections that have stalled the project for years, no homes will be taken while improvements are earmarked to local power stations and drainage. The project also includes retaining and sound walls.

Lieber said the undertaking will ease a bottleneck along a corridor that carries about 40% of the railroad’s riders and from 2013 through 2016, has experienced nearly 4,400 late or canceled trains.

In addition, said Lieber, the project will enable peak-hour reverse commuting, a rising trend in the region. Roughly 80% of riders to Metro-North’s Fordham station in the Bronx, for example, are outbound.

“This is the opportunity to give people in Queens, Brooklyn and western Nassau [County] the same access to jobs that are outside the city that Bronx residents enjoy through Metro-North,” said Lieber.

Approval came after several warnings from board members about the MTA's track record on large capital projects. The Second Avenue subway and East Side access – the latter designed to funnel LIRR trains to Grand Central Terminal on Manhattan’s East Side, to which third track is essentially a companion project -- have been late and over budget.

The cost estimate for East Side access has spiraled to $10.2 billion from $4.3 billion, with completion nowhere in sight.

“It bothers me to go ahead without knowing where we stand [on East Side access],” said board member Andrew Saul. “One of the reasons the MTA is the situation it’s in is that these megaprojects have been eating our capital budget alive.

“These major projects are a major reason why this system’s in trouble today. Who knows if this is the end cost?’”

Gov. Andrew Cuomo in late June declared a state of emergency for the MTA, which operates New York City’s subways and buses, LIRR and Metro-North commuter rail, and several intraborough bridges and tunnels. It is one of the largest municipal issuers with roughly $39 billion in debt.

Joseph Lhota, who returned to the MTA as chairman in June, has formed working committees of board members to study construction costs and procurement overhaul.

“This agency has got to be better about the initial baseline estimates that they put out,” said board member Veronica Vanterpool. “As an agency we can’t just keep throwing numbers out there any more that are not initially reflective of real costs.”

According to Vanterpool, the MTA could advise Long Island communities – however delicate the relationship – about maximizing “value capture,” or building tax revenue around transit-oriented real estate development.

Nassau, the western of the island’s two counties, has a new county executive in Democrat Laura Curran, who will take office Jan. 1. Fiscal overseer Nassau Interim Finance Authority has ordered the county to cut $17 million from its budget.