Local government investment pools sponsored by states and municipalities currently account for $882 billion in assets and are mostly free from any Securities and Exchange Commission regulations, per a recent report.

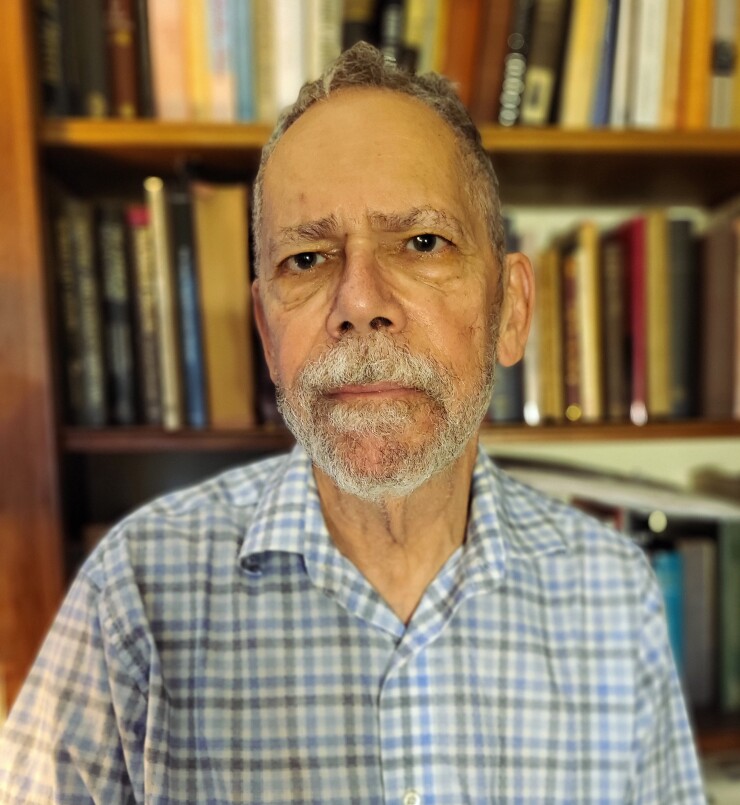

"Local government investment pools are like money market funds," said Marty Margolis, founder of the Public Funds Investment Institute. "They are in many respects, the investment vehicle of choice for smaller and mid-sized local governments and they're not very transparent."

The PFII published a

The programs are not known to be major players in the municipal bond market. "Some of the states have some minor positions in municipal bonds," said Margolis. "Many of the investment policies for these LGIPs are relatively restrictive, they may say 'you can buy municipal bonds but only in the state that you're in.'"

Tax exempt munis offer no advantage to the pools and taxable municipal bonds appeal to different markets of investors.

Although LGIPs remain shielded from SEC regulation the sponsors do take direction from the Government Accounting Standards Board, the Government Finance Officers Association, the National Association of State Treasurers, and the National Association of State Auditors Comptrollers and Treasurers.

Fitch Ratings tracks two indices tied to LGIPs and show an aggregate asset increase in LGIP investments for the first quarter of 2024.

Per Fitch, "Combined assets for the Fitch Liquidity LGIP Index and the Fitch Short-Term LGIP Index were $617 billion at the end of 1Q24, representing an increase of $12 billion quarter over quarter and an increase of $57 billion year over year."

"The Fitch Liquidity LGIP Index was up 4.1% QOQ while the Fitch Short-Term LGIP Index was down 1.6% QOQ, compared to an average increase of 5.4% and decrease of 0.7%, respectively, in the first quarter over the past three years."

S&P Global Ratings also selectively tracks LGIPs through a weekly index. "There's a subset rated by S&P, and it has grown by 17% in the last two years, and 9% in the last year, so it's not grown as fast as the bigger money fund industry, but it's grown," said Margolis.

The big advantage of the pools is allowing the sponsors to get into markets with higher obstacles to access.

"If you're a large city or county with a $500 million- or billion-dollar portfolio, and you're in the marketplace for $25 or $50 million of securities in a week, but the way the markets are these days, nobody cares," said Margolis. "You'd have a really difficult time, getting good coverage, good offerings, good prices, and interacting with a market that's really geared to the $100 billion dollar investment."

Margolis believes the lack of regulatory oversight and disclosure throttles investment from eligible government agencies.

"You've got states where there are three, four, five or six, competing LGIPs," he said. "The amount of information on portfolio structure and holdings that's available may be much less than what's available to investors who invest in money funds. So, you might be not quite sure what you're investing in."

Operational risk is another downside to LGIPs. The state of Florida and its pool had a financial meltdown 2007 and was followed by King County, Washington in 2008. Orange County California's bankruptcy in 1994 was attributed to bad bets placed by its LGIP.