Illinois piled nearly $4 billion onto its unfunded pension liabilities in fiscal 2020 as statutorily based payments fell well short of actuarial requirements and amid lackluster investment returns dampened by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The unfunded liabilities rose $3.8 billion, or 2.8%, to a new peak of $141 billion in fiscal 2020 from $137.2 billion in 2019.

The system of five funds that cover teachers outside Chicago, state employees, public university professionals, general assembly members and judges is collectively 40.4% funded, from 40.3% for 2019, according to a

“The primary reason was, again, actuarially insufficient state contributions” which accounted for 58% of the increase,” the report said. “There were three more factors that worsened the unfunded liability. One was an actuarial loss that resulted from lower-than-assumed investment returns by all the five systems due to the COVID-19 pandemic,” which accounted for 36.5% of the growth in liabilities.

The fiscal 2020 results will drive 2022 contributions up by $790 million, or 8.1%, to $10.6 billion in fiscal 2022 from $9.8 billion in fiscal 2021, adding to the state’s budget strains. The general fund piece rises by $746 million to $9.5 billion from $8.7 billion.

The combination of structural budget gaps and underfunded pensions have dragged Illinois' ratings down to the final level above junk. Fitch Ratings, Moody’s Investors Service and S&P Global Ratings assign negative outlooks and Gov. J.B. Pritzker is currently working to close a $4 billion budget hole.

All five funds saw positive investment returns but they missed their mark on assumptions that range from 6.5% to 7%.

Demographic changes due in part to unexpected early retirements and salary increases also had a slight impact on unfunded growth. A pension buyout program initiated by former Gov. Bruce Rauner for three of the state’s five funds and continued by Pritzker did not result in either actuarial gains or losses in fiscal 2020 although two of the three recorded an actuarial gain from the program in 2018 and 2019.

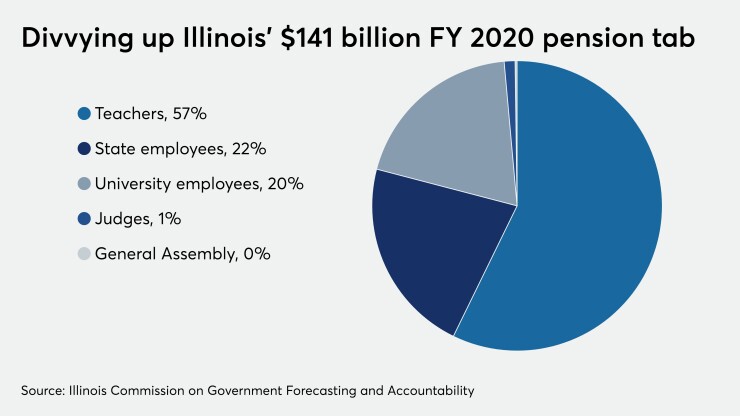

The teachers' system accounts for $80.7 billion of the actuarial tab, the state employees' system accounts for $30.8 billion, and the state universities system accounts for $27.5 billion, with the judges and General Assembly systems making up the remainder.

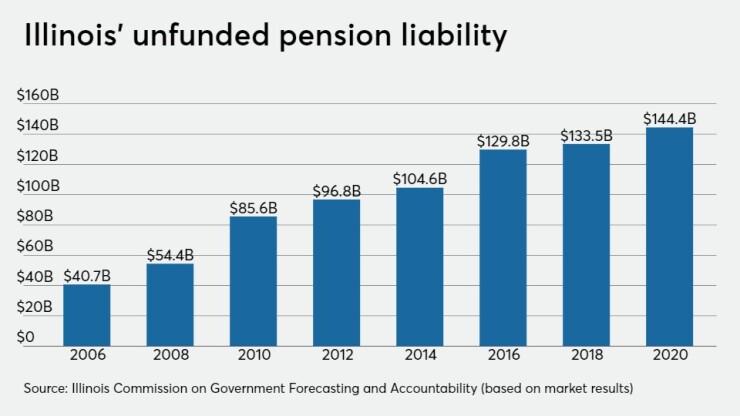

The actuarially based numbers incorporate smoothing of investment results and other factors over five years to avoid big one-year fluctuations in state contributions. On a market-based assessment of the funds the unfunded tab rose to $144.4 billion from $137.2 billion.

The market-based funded ratio of 39% was down from 40.3% in 2019 with the General Assembly fund at the weakest level of 17.1% and the teachers fund at the highest at 40.5%.

The Teachers’ Retirement System saw just a .5% return, the State Employees’ Retirement System saw a 4.5% return, the State Universities Retirement System saw a 2.6% return, the Judges’ Retirement System recorded a 4.5% return, and the General Assembly Retirement System recorded a 4.3% gain.

The TRS board pointed out that it saw a dramatic falloff due to the pandemic as midway through the fiscal year its return was at 13.41%. “Everyone took a hit during the early months of the pandemic,” TRS Acting Executive Director Stan Rupnik said in a statement. “But the investment strategies we have in place limited losses and have allowed us to prudently rebuild the portfolio’s value.”

All totaled the latest actuarially reports reviewed by COGFA put the overall statewide tab of unfunded pension liabilities around $208 billion.

That includes the state’s fiscal 2020 figure of $141 billion, the Chicago area and statewide municipal employees fund totals of $56.1 billion based on 2018 results, and the downstate and suburban public safety funds $11 billion burden based on 2017 results. The latter two figures don’t take into account more recent results released by local governments. Chicago's

History

The unfunded liabilities have been on a largely uninterrupted march upward since 2006 when the market-based tab stood at $40.7 billion. Unfunded liabilities have fallen in only two years since.

The biggest leap occurred in 2016 when the figure rose to $130 billion from $111 billion.

“One of the main drivers continues to be actuarially insufficient state contributions determined by the current pension funding policy” under the 50-year funding ramp adopted in 1995 that’s designed to reach a 90% ratio by 2045. “There is a distinction between contributions that are statutorily sufficient and contributions that are considered actuarially sufficient.”

Under the funding schedule, the state is required to make contributions as a level percent of payroll in fiscal years 2011 through 2045. The contributions are required to be sufficient, when added to employee contributions, investment income, and other income, to bring the total assets of the systems to 90% of the actuarial liabilities by fiscal year 2045.

Under the schedule, the unfunded liabilities are projected to hit a high of $151.4 billion in 2027 before beginning a descent. The $10.6 billion fiscal 2022 contribution is projected to rise to $13.4 billion in 2032, $18.4 billion in 2042, and $19.8 billion in 2045, the final year of the ramp.

A 50% funded ratio isn’t hit until 2031.

The state’s $10 billion pension bond issue in 2003 pumped $7.3 billion into the system helping hold the funded ratio steady through fiscal 2007 in the 60% range. The other $2.7 billion covered near-term contributions. Plummeting investment returns in fiscal 2008 and 2009 eroded the funded ratio and it dropped to 38.5% in 2009.

While stronger investment returns by 2011 helped boost the funding ratio to 43.3% they were erased the following year. The funded ratio hit a low of 37.6% in 2016 and since then the funded ratio has hovered around 40%.

The recent

Pritzker continued Rauner's buyout program and is exploring asset sales to bolster funding levels but has not outlined a larger fix.

Voters rejected his constitutional amendment on the November ballot to move to a progressive income tax structure which would have funneled an additional $100 million in annual funding and eased other strains on the general fund. He dropped a plan to re-amortize the funding schedule in 2019 amid legislative opposition and warnings it could trigger a downgrade after April income tax receipts came in stronger than expected.

The state has little room to maneuver given the Illinois Supreme Court has ruled cuts violate the state constitution. Pritzker resisted calls from some to seek a constitutional amendment to give the state some flexibility on benefits because saying he believes pensions are a promise and must be honored and cuts would likely face a legal challenge even if the constitution was amended.