CHICAGO – Illinois public universities face obstacles, from ongoing state political dysfunction to poor enrollment trends, as they begin the long slog back to what they hope is fiscal health after the end of the state’s historic budget impasse.

The reputations, balance sheets, and ratings of Illinois’ nine public universities all were battered by the budget gridlock that ended with passage of a $36.1 billion budget package in July after some GOP members broke with Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner and joined Democratic majorities to override his budget veto.

Appropriations during the stalemate were limited, damaging all of the schools. Regional schools that rely more heavily on state aid were especially hard hit.

Many dipped deeply into reserves, cut programs and staff, raised tuition, and cut some school days. The Higher Education Learning Commission warned earlier this year that the accreditation status of some schools was at risk if the impasse continued. Such a loss would block the flow of federal student aid.

While Illinois averted the black mark of becoming the first sovereign state to lose its investment grade rating by finally passing a budget, most of the state’s public universities did not.

Only two – the flagship University of Illinois and Illinois State University – held on to investment grade ratings from Moody’s Investors Service and S&P Global Ratings. Community colleges also suffered but not as much as the universities because the two-year schools rely more heavily on their local property tax base than state aid.

“As long as the state is in state of disrepair, it’s going to be hard to convince the rating agencies that things can be turned around,” said Howard Cure, director of municipal bond research at Evercore Wealth Management LLC. “You need state involvement and resources.”

S&P is watching the balance sheet recovery as well as enrollment and faculty trends closely with its one year outlook on the schools it rates at stable, said S&P Global Ratings Ashley Ramchandani. “It could be a long road back,” she said.

The universities had long been warning about the dire, long-term impact of the funding drought and recent reports highlight the damage, from enrollment losses to faculty losses.

LATEST DATA

The state’s public colleges and universities lost more than 72,000 students, eliminated nearly 7,500 jobs, and the strains cost the Illinois economy nearly $1 billion per year, according to

The nine public universities are Chicago State University, Eastern Illinois University, Governors State University, Illinois State University, Northern Illinois University, Northeastern Illinois University, Southern Illinois University (which operates two campuses), Western Illinois University, and the flagship University of Illinois, which operates three campuses.

“Faced with a $660 million cut in state support, many institutions exhausted their financial reserves, raised tuition, experienced credit downgrades, cut programs, laid off workers, and reduced in enrollment. Even with most funding now restored, damage has been done that will have a lasting impact on the state’s economy,” said co-author Robert Bruno, a University of Illinois professor.

In-state tuition and fees at the universities rose on average by 7% or about $900 during the impasse and hit as much as 14% at some schools. Enrollment declines were experienced in every region of the state, but were most acute in the Northeast and Southern regions.

“The uncertainty and higher costs triggered by the stalemate drove tens of thousands of students — and a sizable segment of our future labor force — to either pursue educational opportunities out of state, or not at all,” said ILEPI policy director Frank Manzo IV, a co-author of the study.

The “fiscal strain on universities and colleges cost the Illinois economy about $1 billion each year,” the study concluded.

Fall enrollment this year declined by 2% from academic year 2016 and by 4% from academic year 2015, according to

Eastern, Chicago State, the University of Illinois Springfield campus, and Southern’s Carbondale campus all were stung by losses of at least 10% while Governors State and Western saw declines of 9%.

Only two campuses operated by the nine schools gained students. The U of I Chicago campus saw a 5% increase while its main campus at Urbana-Champaign saw a 2% gain.

Other states have been recruiting Illinois students and losses occur “when word gets out that a state has been making cuts and is not as supportive of its universities as other states and its facilities may be lacking,” Cure said.

Illinois may have budget now but Rauner and Democrats remain deeply at odds and it’s unclear whether the two sides can reach agreement on the next budget and a new capital program. The previous program has mostly expired without the needed revenue to support borrowing. The state’s unpaid bill backlog remains at about $15 billion straining the state’s ability to keep up to speed on aid payments.

“I think the universities are still under a lot of pressure financially and it’s going to show in facilities and the ability to attract students,” Cure said. “It’s hard to reverse that trend.”

There are many demands on the state and higher education could take a backseat, especially if an economic downturn strikes, Cure added.

Universities will continue to pay a “big penalty” when borrowing because they are a victim of the state’s financial health, Cure said, but they benefit from a general market perception that it’s unlikely the state would allow its most at risk regional universities to go under.

NEW BUDGET

The fiscal 2018 budget offered both good and bad news for higher education. After two years of uncertain funding, the budget provided funding clarity, but it also included a 10% cut from the fiscal 2015 base level before the impasse.

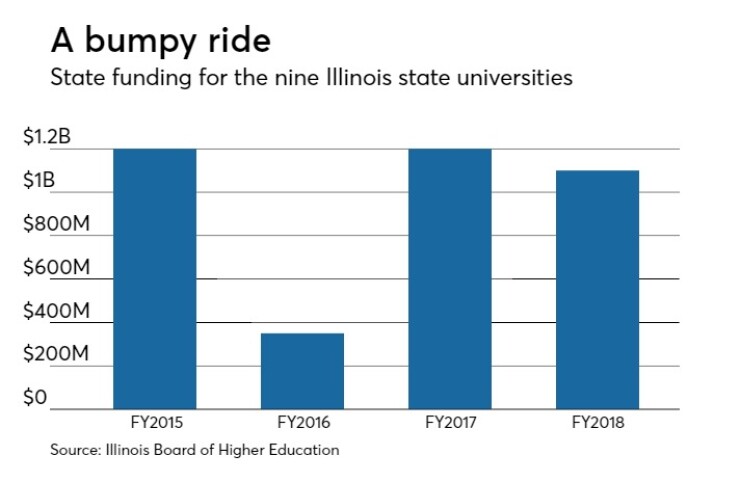

The state’s public universities received a total of $1.2 billion in fiscal 2017 from previous stopgap appropriations and the new fiscal 2018 budget and fiscal 2018 appropriations were set at $1.1 billion, according to a memorandum from the Illinois Board of Higher Education chair Tom Cross.

Universities never received a full appropriation in fiscal 2016, the Civic Federation of Chicago

While universities will receive $1.2 billion for fiscal 2017 and $1.1 billion for fiscal 2018 they only received $350 million for fiscal 2016, sharply down from the $1.2 billion fiscal 2015 base level.

When community college funding, student aid, and other higher ed spending is added the total appropriation for fiscal 2016 rises to $623 million. For fiscal 2017 the total is nearly $2.2 billion and the fiscal 2018 total is $1.8 billion while the base funding level for fiscal 2015 was $1.9 billion.

RATINGS

The last rating action from S&P came in July. It took the ratings of the seven universities it rates off watch and raised four.

With the one notch upgrade to BB-plus, Southern Illinois and Governor’s State moved closer to restoring the investment grades they lost during the impasse. Northeastern and Eastern were upgraded to B-plus from B. All four schools now carry a stable outlook.

S&P affirmed the A-minus ratings of the flagship and Illinois State and assigned stable outlooks. Western’s BB-minus rating was affirmed and assigned a positive outlook. Illinois is the lowest rated flagship university in the 50 states.

S&P had stung some of universities with downgrades in April that left a total of five in junk territory. The swift path from investment grade to junk as the impasse ensued was “unprecedented” and it impacted the rating agency’s median rating levels for regional state schools, said Ramchandani.

For some schools, Ramchandani said, it got to the point where the conversation focused on “where in this waterfall does debt service fall?” as they struggled to meet payroll and keep classes going.

While assigning a stable outlook, it’s a “precarious stability” as future state support is unclear and the state was already facing declining student demographics while “some schools have already hit up reserves so they are in a more vulnerable position,” she added.

Moody’s Investors Service last struck in June, downgrading all seven universities it rates, leaving only U of I and Illinois State with investment grade ratings.

U of I’s main borrowing credit is rated A1, the lowest among comparable flagships. The outlook on all seven remains negative. Other than Illinois, Moody’s rates only three other public universities at the speculative grade level, the lowest of which is University of Puerto Rico at Ca.

The universities continue to face “material challenges,” said Moody’s analyst Diane Viacava. Enrollments declined across nearly all of the universities, with a number of schools reporting significantly lower freshmen classes, and it’s uncertain how they can grow enrollment given the state and regional demographics. Enrollment impacts tuition revenue and state operating appropriations were cut 10%.

“The universities’ liquidity was heavily depleted and is unlikely to return to historic (pre-2016) levels given the weak revenue trends, as well as the uncertainty of the timing of the payment from the state for the remainder of fiscal 2017 that is budgeted from the General Revenue Fund,” she added.

Comptroller Susana Mendoza’s office immediately released $523 million in special funds after the budget passed to cover some operating aid and student aid payments, said comptroller spokesman Abdon Pallasch. The office has released 13% of the $625 million owed from the general fund in fiscal 2017 aid while it will dip into the education assistance fund for fiscal 2018 aid payments. While the office remains behind on payments, the timing has improved and the office is in communication with universities to provide them more clarity on when aid will be disbursed, Pallasch said.

The nine schools rely on the state for about 40% of their operating funds, although the percentage is lower for the flagship. The nine schools carry more than $2 billion in outstanding debt, with most issuing under two structures – certificates of participation and auxiliary revenue bonds.