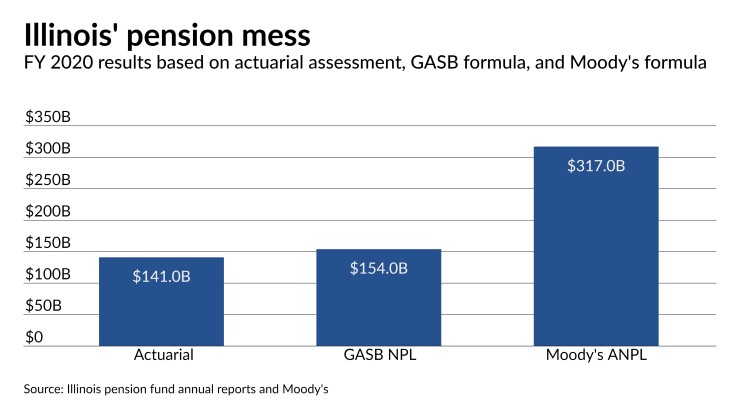

Illinois’ pension hole deepened last year, hitting a new peak that topped $300 billion, based on the formula Moody’s Investors Service applies.

The aggregate adjusted net pension liability grew 19% to $317 billion for fiscal 2020, which ended June 30. It sets a new peak nationally.

Illinois’ growth tracks that of other states, given falling investment rates, but the sheer size of Illinois’ pension burden stands out more prominently than others as a black mark on its long-term fiscal condition. The Federal Reserve is expected to keep rates down to help the economy recover from the COVID-19 pandemic's blows for at least two years, which will generally have a negative impact on pension funds nationally.

The jump “was driven largely by falling interest rates,” Ted Hampton, Moody’s lead Illinois analyst, said in the report published Wednesday.

Analysts project that about 80% of the adjusted net pension liability (ANPL) increase across Illinois' five retirement systems is due to falling market interest rates. Weaker-than-assumed investment performance also contributed to unfunded liability growth. The state's largest pension system, the Teachers' Retirement System reported an investment return of 0.52%. It assumes a 7% return.

The state last fall reported its unfunded pension liabilities for fiscal 2020

The state’s comprehensive annual financial results for fiscal 2021, which are not yet published, will also include a net pension liability figure of $154 billion, up from $145 billion, under Government Accounting Standards Board rules. The NPL varies in the assumptions and reflects a weighted average discount rate of 6.74%.

Liabilities reported under GASB rules and actuarial funding formulas are based on discount rates tied to the assumed rate of investment return on pension assets, which veer from market interest rates for high-grade fixed income securities.

Moody’s applies in its ANPL the FTSE Pension Liability Index, a high-grade corporate bond index, to value state and local government pension liabilities, which it believes is a better measurement of accrued liabilities versus the assets set aside to pay for them. That index fell to 2.70% as of June 30, 2020, from 3.51% the prior year.

When factoring in the state’s other post-employment benefits liabilities and bonds, the state’s long-term liabilities for 2019 equaled about 39% of state gross domestic product for 2019. Only Connecticut is higher at 41% with New Jersey closely following at 38%. Moody’s expects Illinois’ percentage to rise to 48% in the next reporting cycle.

The ANPL underscores “Illinois' growing pension challenges” but “even with the substantial increase in long-term liabilities … the near-term funding and cash-flow positions of the state's pension systems will remain relatively unchanged,” said the report.

That matters since a growing negative number signals greater difficulty in increasing assets to cover benefits. The Teachers’ Retirement Fund held nearly steady at a negative 2.3% for non-investment cash flow relative to system’s assets and its assets-to-benefit coverage ratio held steady at 7.5 years.

The report lays out the numbers but does not impose any credit assessment.

The state’s chronic underfunding of pensions — with contributions driven by a statutory formula based on a percentage of payroll needed to reach a 90% funded ratio in 2045 — weigh heavily on the state’s rating that is at the lowest investment-grade level, and carries a negative outlook.

“Illinois is an outlier among states both for fiscal challenges from pension expenses and for its limited capacity to modify the benefit packages that drive these expenses,” Moody’s wrote.

Gov.

But on a positive note, the budget avoids “any suggestion that the state would scale back near-term pension contributions to alleviate fiscal pressure from the coronavirus pandemic, which would ultimately make the pension challenge harder to address,” Moody’s said.

It’s unclear whether passage of the budget as proposed and an infusion of federal aid now before Congress could help return the state’s outlook to stable. Moody’s, Fitch Ratings and S&P Global Ratings all rate the state at the lowest investment-grade level and moved their outlook to negative early in the pandemic.

Factors that could drive a Moody’s upgrade include enactment of recurring financial measures that support structural balance, actions to improve pension funding, and progress in lowering the state’s bill backlog that does not rely on either long-term borrowing or a decrease in non-operating fund liquidity.

Pritzker in 2019 pitched a pension borrowing and re-amortization of the 50-year funding schedule but dropped those proposals. A special task force continues to explore asset sales and leases to raise funding levels. The governor had earmarked for pensions $200 million from the $3 billion expected from a move to a graduated income tax rate from the current flat tax.

Voters shot down that constitutional amendment in November. New House Speaker Emanuel “Chris” Welch, D-Hillside, recently suggested that if the state were to take a second attempt at putting the measure on the ballot, the new funding be tied to an issue such as the stabilization of pensions.