Private-sector involvement could help satisfy a repair backlog and trigger an overhaul at the New York City Housing Authority.

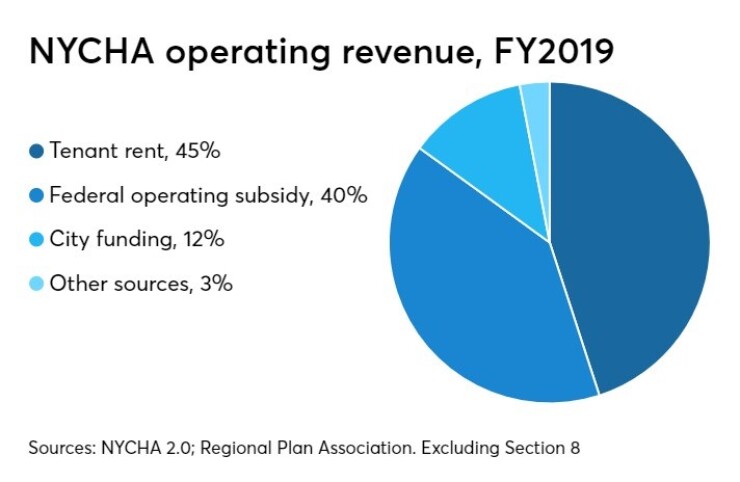

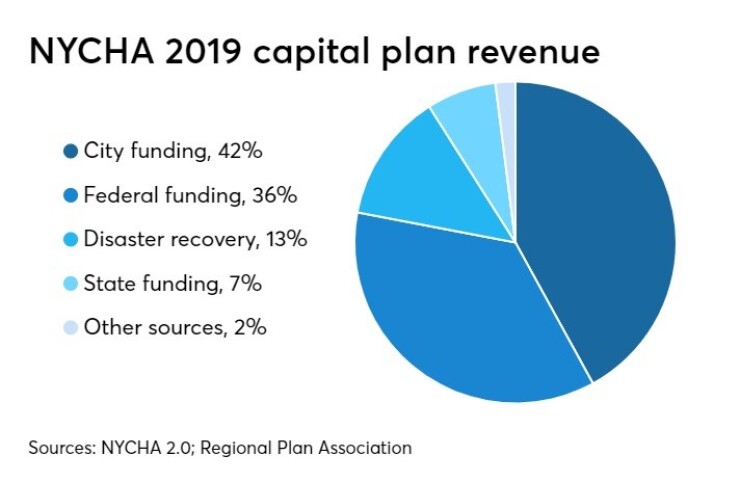

The authority, long a strain on city operating and capital budgets and with a track record of fiascoes and mismanagement, has a backlog of $32 billion over five years and $45 billion over 20, according to its most recent needs assessment.

Its well-headlined woes have prompted a raft of suggestions for how best to rebuild the agency and earmark funds.

"Like with any public infrastructure, if you defer maintenance, costs start to spiral," said Moses Gates, a vice president for housing and neighborhood planning at think tank Regional Plan Association. "A dollar today is two dollars tomorrow. We've experienced that with our subways and our bridges and we're now experiencing that with our public housing."

RPA's October report, “

RPA called for making NYCHA the centerpiece of New York’s housing plan, enabling the authority to tap the resources of the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development and Housing Development Corp. "Right now it's siloed, and that's really time to end," Gates said.

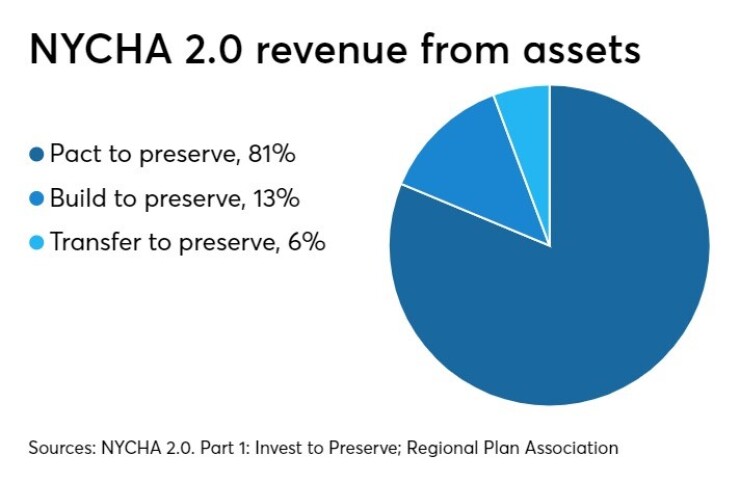

Additionally, RPA recommended creating a separate development entity akin to the School Construction Authority; ensuring high-end real estate contributes its fair share to the authority; and generating long-term revenue by supplementing NYCHA's Transfer to Preserve program — including air rights — with new options.

“I like the idea of getting the private sector more involved. Frankly, the city does not have the resources to solve all the problems,” said Howard Cure, director of municipal bond research for Evercore Wealth Management.

NYCHA’s recently announced transfer of development rights at the Ingersoll Houses in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, falls under Transfer to Preserve. The deal involves transferring about 91,000 square feet to a nearby planned residential tower developed by Maddd Equities LLC and Joy Construction Corp. In exchange, the NYCHA units there will get $25 million for repair work.

Problem areas systemwide include lead and mold exposure, broken elevators, heating outages and leaky roofs.

According to the watchdog Citizens Budget Commission, NYCHA is on pace to meet its short-term target for increasing public-private partnerships. Still, said CBC, it cannot meet its long-term goal of converting 62,000 units without shifts in the allocation of state and local housing funding, federal regulatory relief and additional federal funding.

Involving the private sector in New York can be politically prickly and laden with controversy. Pushback from public officials and community groups has stalled the authority, while the Daily News reported that the Ingersoll builders are also campaign donors to Mayor Bill de Blasio.

RPA said the layout of many NYCHA developments and rules governing the transfer of rights limit the program. “Development rights are allowed only to be transferred to a site on the same block — and NYCHA developments often occupy the entire block themselves, leaving nowhere to transfer these rights,” the report said.

A citywide zoning text amendment, Gates said, could enable NYCHA work around the problem. This could mirror other such districts, notably East Midtown surrounding Grand Central Terminal.

NYCHA, which serves 400,000 residents or about 5% of the city's population, also faces funding uncertainty from Washington and angry local politicians and tenant groups.

Shola Olatoye resigned as NYCHA chief executive under pressure in April 2018 amid reports of poor living conditions and a city Department of Investigation report that accused Olatoye and her staff of lying about lead-paint certifications and mold statistics to federal regulators.

Federal district judge William Pauley ordered the monitor. Bart Schwartz, a former assistant U.S. attorney in the Southern District of New York and chairman of investigations firm Guidepost Solutions, filled the position in March.

NYCHA and Schwartz two weeks ago announced an action plan that will govern the allocation of $450 million in New York State capital reimbursement funds.

"I'm not getting into the fray about how you finance public housing in America, the privatization and all the other issues," Schwartz said Friday at New York Law School. "If I did that, then I'd never be able to focus on the things that I'm really there to handle, and it's not very romantic. It's rats, it's mold, it's garbage, it's lead-based paint."

Gregory Russ, the former Minneapolis Public Housing Authority executive director, took over as CEO in August. His track record includes privatizing public housing under the federal Rental Assistance Demonstration program.

Improving NYCHA, according to Cure, requires cooperation among several agencies. “It also requires the engagement of the city and the politicians with the residents,” he said. “There’s a lot of distrust because NYCHA has basically been mismanaged for so long.”

Cure likes RPA’s idea of a new civic advocacy coalition similar to the mass transit movement that has mushroomed since the founding of the Straphangers Campaign.

“That’s very intriguing,” he said. “These are poor people not represented well and it would help to have an agency that speaks for them.”

An organization parallel to the School Construction Authority, Gates said, would be free from cumbersome regulations. "We want an agency that's nimble enough to be able to deliver the capital projects in addition to just getting the funding."

Skyrocketing real estate values, said RPA, present a revenue opportunity for public housing while helping grasp some of the larger inequities in the property tax system. New options could include directing revenue from any pied-a-terre tax and eliminating the cooperative and condominium abatement for the top 10% of properties to NYCHA capital repairs.