BRADENTON, Fla. – Key assumptions underpinning Kentucky’s pension system propelled a meteoric rise in unfunded obligations that led some analysts to call it the worst-funded state retirement plan in the country.

Those assumptions spurred a $25.5 billion increase of unfunded actuarial accrued liabilities among the Bluegrass State’s eight pension plans between 2005 and 2016, according to a May 22

The plans had $62.3 billion of combined unfunded liabilities as of June 30, 2016.

The report – the second in a series of three - also found that Kentucky’s pension systems had a combined $6.9 billion negative cash flow over the 11-year study period as benefits paid to retirees, plus program expenses, exceeded appropriated funding.

A top reason the state’s liabilities grew at such a fast pace, PFM said, was that it used a level percentage of payroll funding as part of the process to determine its annual required contribution over a period in which the state’s workforce declined.

“The formula has gone sideways,” State Budget Director John E. Chilton told The Bond Buyer. “Kentucky used a really common formula to provide funding based on a percentage of payroll.”

The method works well in states with increasing payrolls.

But Chilton said Kentucky’s state workforce has seen minimal wage growth over the past decade and the total employee head count has decreased, undermining the assumption used to fund the ARC.

Like Kentucky, a number of states have pared their workforces since the recession and use a percentage of payroll funding to determine their annual pension contributions – a formula that PFM says creates “actuarial back-loading” with “negative amortization.”

Principal payments are allocated heavily toward the end of the amortization period, and in the early years payments may not be large enough to offset interest on the unfunded liability, creating negative amortization.

While the approach promotes “affordability and budgetary stability,” PFM said it results in smaller near-term payments than would be required under the alternative “level dollar” amortization method that sets all payments at the same level year-after-year.

Here’s what PFM found examining the Kentucky Employees Retirement System – the state’s second-largest plan for non-hazardous employees, with 37,779 active members and 44,004 retired members and beneficiaries.

KERS-NH assumed annual payroll growth of between 3.5% and 4.5% during the actuarial valuations prepared since fiscal 2006.

But the size of the workforce dropped by 19.8% during that period, PFM said.

According to the most recent valuation by Cavanaugh Macdonald Consulting LLC, KERS was 16% funded and the 2,423-member State Police Retirement System was 30.3% funded as of June 30, 2016.

“It should also be noted that the retirement fund of the KERS Non-Hazardous Retirement System and the SPRS Pension Fund are both in critical condition,” Cavanaugh wrote in a cover letter to retirement system board members.

The state’s largest pension fund – the Kentucky Teachers’ Retirement System with 123,411 members – was 54.6% funded in fiscal 2016 in part because the state has not paid the required ARC to support the plan since fiscal 2008, Cavanaugh said.

Failure to make the full contribution is expected to push annual payments the state should make to $553.6 million in fiscal 2019 from $60.5 million in fiscal 2009, TRS Executive Secretary Gary Harbin wrote in a cover letter to the latest valuation.

Kentucky’s poorly funded pension plans and inaction in addressing the problem has prompted some municipal investment firms to shy away from the state's bonds.

“We are still cautiously monitoring Kentucky,” Gurtin Municipal Bond Management partner Tom Schuette said Tuesday.

In early 2015, Gurtin expressed concern about Kentucky and Connecticut as “outlier” states with deteriorating pension funding levels likely to create budgetary stress in future years.

At the time, the firm said it would not add further exposure to either state’s debt, while waiting to see how each one approaches pension contributions in upcoming budget cycles.

"Given the reform efforts and the significant boost in funding that was in the last biennial budget, we have been selectively adding exposure" to Kentucky, said Schuette, who is also co-head of investment research & strategy.

"But they are on a tenuous path," he said, adding, "If the state begins to waver in its commitment to increased funding, we would likely revisit our position."

Schuette said the state has instituted reforms in the employee pension plan for new hires and has made progress toward meeting actuarial required contributions.

“However, the scale of work that remains is significant, and policymakers need to show the market that they have the discipline and willingness to stick to a plan even in down cycles,” he said.

In September, Cumberland Advisors said it had placed the direct obligations of four states - Illinois, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Kentucky - on its “do not own” list, citing concerns over pension funding, deficits, and legislative inertia.

Rating agency analysts have also warned Kentucky for years about what they believe is the lack of progress resolving the state's pension problems.

In January, S&P Global Ratings placed a negative outlook on the state’s A-plus issuer-credit rating and warned that while Kentucky has made incremental progress in addressing underfunded pension obligations, “it is our opinion that some plan assumptions may be overly optimistic.”

“If pension funding levels continue to decrease significantly and pension plan liquidity worsens to the point we believe increasing future costs will materially affect our view of the state's ability to return to structural balance over our two-year outlook horizon, we could lower the rating,” said S&P analyst Timothy W. Little.

S&P said Kentucky had the worst-funded aggregate pension ratio at 37.4% in fiscal 2015, followed by New Jersey at 37.8%, Illinois at 40.2%, Connecticut at 49.4%, and Rhode Island at 55.5%.

In January, Moody's Investors Service warned Kentucky that failure to address its large pension liabilities could lead to a downgrade of its Aa2 issuer rating.

Moody’s, which maintains a stable outlook, said Kentucky's pension liabilities are among the highest of all states and will remain a drag on the commonwealth's credit profile over the long term.

While affirming its AA-minus issuer-default rating and stable outlook in January, Fitch Ratings said that pension contributions will be a driver of the state’s overall expense growth given erosion in the funded ratio of its major plans.

Last year, under then-newly elected Gov. Matt Bevin, the Legislature adopted a 2017-2018 biennial budget that included an additional $1.4 billion in contributions for KTRS and the non-hazardous KERS, though the added contribution to the final payment was still short of the full ARC funding for KTRS.

Bevin, a Republican who said pension reform is a top priority for his administration, announced in September that the state hired PFM to study the state’s pension systems and recommend reforms.

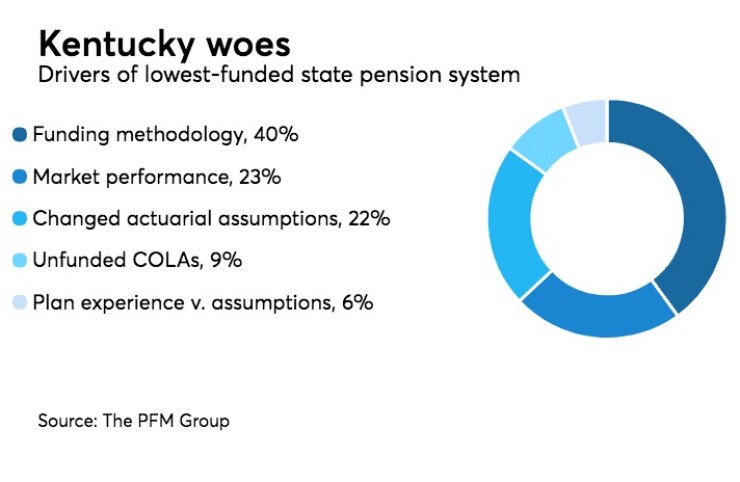

The 267-page historical and current assessment PFM released this month found that 25% of the $25 billion increase in Kentucky’s pension liabilities are attributable to the use of the level percentage of payroll funding method leading to negative amortization.

Kentucky isn’t alone in the use of the methodology.

“Amortization is a serious issue,” Jean-Pierre Aubry, associate director of state and local research at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, said Tuesday. “About a third of large state and local plans use amortization methods that cause negative amortization.”

The CRR found in a 2012 study of amortization methods for unfunded liabilities, that 34 state and local plans used a closed level percent of pay method approach, which dictates that total unfunded liabilities must be paid off by a certain date.

In the case of KTRS and KERS, the amortization period was reset periodically over the years, a factor that has hindered Kentucky from making progress toward paying down the unfunded liabilities, according to PFM.

In assessing other factors that drove the increase in unfunded liabilities over the study period, PFM said 22% was due to changes in actuarial assumptions to reduce the discount rate, update mortality tables and reflect demographic patterns.

ARC underfunding and market performance assumptions tied at 15% each as contributors to the increased liabilities, while 9% was attributable to the state granting cost-of-living adjustments without providing additional funds.

Market investment performance drove 8% of the total unfunded liability, while 6% was caused by actual plan experience differing from plan assumptions.

Chilton said the next step in the pension reform process will be getting input from plan administrators before PFM issues its final report in the late summer or early fall recommending actions that the state can take.

The state has already recognized additional funding will be needed, he said.

The governor has announced plans to call a special session of the Legislature likely in late August or early September to deal with pension and tax reform issues, and he has indicated that the measures he will consider won’t be revenue-neutral, Chilton said.

Bevin has suggested moving away from the personal income tax that now funds a majority of the state budget to one that is more dependent on sales tax revenues.

“We want to keep the promises we made” to retirees, Chilton said. “In the final analysis, there are only three things we can do – increase revenues, decrease expenses in other areas of state government, or adjust benefits – we’re thinking about everything.”