Long-struggling Harrisburg has received enhanced taxing authority from Pennsylvania that city officials say will help it refinance debt and avoid another fiscal cliff.

“This is tremendously important to Harrisburg for generations,” Mayor Eric Papenfuse said in an interview.

State lawmakers, through the

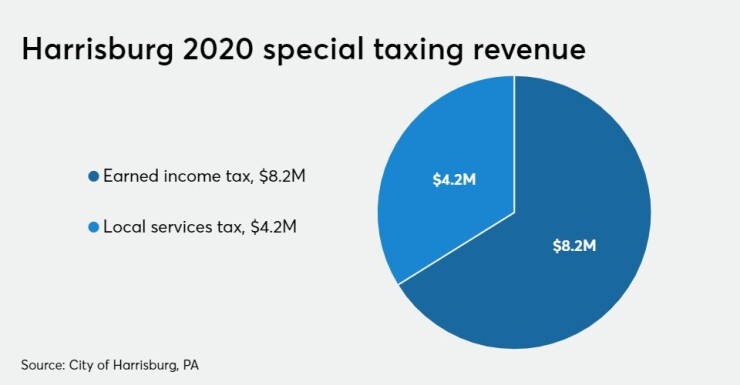

The taxes generate a combined $12.4 million in revenue, or about 20% of the city’s annual operating budget prior to the City Council’s approval of a $79.2 million spending plan on Monday. The new budget emphasizes debt reduction, capital projects and enhancing city services.

“There aren’t too many tools in your toolbox to cover a 20% gap to your operating budget. The cuts would have been devastating,” said the city’s financial advisor, Dan Connelly at Marathon Capital Strategies.

Harrisburg’s distressed status under the state-sponsored workout program known commonly as Act 47 enabled the taxing authority, which was to expire in 2024.

“They pushed it out so far that it is really beyond the bills that we currently accumulated,” Papenfuse said. “They pushed it out, really, a generation, and that is going to be exactly what we need to continue paying off Harrisburg’s debt.

“This was this cloud that was hanging over us and making it hard for financial institutions to look at the city or take the city’s financial planning seriously.”

Unrated Harrisburg expects to petition the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania to exit Act 47 early next year.

Storm clouds have long hung over 49,000-population Harrisburg, which sits along the Susquehanna River. Piles of debt, primarily from bond financing overruns related to an incinerator retrofit project, pushed the city to the brink of bankruptcy about a decade ago.

Harrisburg was part of national discussion about municipal distress, along with Detroit; Central Falls, Rhode Island; Jefferson County, Alabama; and three California cities. Puerto Rico filed its version of municipal bankruptcy in 2017.

Throughout 2011, the City Council, in a series of repeat 4-3 votes that reflected the divide and set a chaotic tone,

The council in October 2011 filed for Chapter 9 protection over the objections of then-Mayor Linda Thompson, but U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Mary France in the Middle District of Pennsylvania rejected the petition a month later, citing a quickly enacted state law that prohibited the city from filing bankruptcy. France also said city leaders had to be on the same page.

Harrisburg defaulted on a series of general obligation bond payments in 2012 and a year later, crafted a recovery plan called “

“I had no idea when he named me how complex this would be,” Lynch said during an

The plan erased about $600 million of crippling debt through the sale of the city incinerator, a 40-year lease of parking assets, creditor haircuts, a balanced budget for four years and funding for infrastructure improvements plus economic development incentives.

Commonwealth Court Judge Bonnie Brigance Leadbetter approved the plan in September 2013. The arrangement also put Harrisburg in Act 47.

Papenfuse, a bookstore owner and former member of the Harrisburg Authority public-works agency, was elected in 2013 and re-elected four years later.

Corruption also plagued Harrisburg. Steve Reed, the city’s mayor for 28 years through 2009 and nicknamed “mayor for life,” pleaded guilty in 2017 to 20 counts, including two felonies, of receiving stolen property.

Federal prosecutors two years earlier accused Reed of diverting municipal bond proceeds to a special projects fund to buy as many as 10,000 Wild West artifacts and other “curiosities” for himself. Reed failed in his attempt to open a Wild West museum.

“I think we have stabilized the city’s finances,” Papenfuse said. “We have quiet, confident leadership now. We’re no longer in the spotlight for what we used to be known for.”

A new restructuring agreement with bond insurer Ambac Financial Group could benefit the city long-term, according to the mayor.

While the city has eliminated its troublesome debts of the past, related to the incinerator and the parking authority, other types of debt remain.

Harrisburg has nearly $25 million in forbearance debt from Ambac covering the city’s 2012 GO defaults, with interest accruing at 6.75%. Final payments are due in 2022.

About $6.5 million remains on city-guaranteed Harrisburg Redevelopment Authority stadium debt, which Ambac also insures, to renovate its minor-league baseball stadium on City Island that is home to the Class AA Eastern League Washington Nationals’ affiliate.

While the city made its 2020 payment of $650,000 on the stadium bonds, even as the pandemic forced the cancellation of all minor-league baseball, future payments are unclear, according to Connelly.

Under an agreement between the city and Ambac, subject to various approvals, Harrisburg will defease the stadium bonds and pay upfront toward the forbearance liability in return for a nearly $2 million credit toward the forbearance liability and lowered interest. The city could also receive up to a 38% credit for any forbearance prepayments of up to $1 million.

“We’d love to have a lower interest rate than 5%. That’s what we were able to end up with,” Connelly said. “It’s definitely an improvement over 6.75%, and I think the ultimate goal. Now that the city’s taxing powers have been extended, is that the city can re-enter the debt markets with and lower that interest rate through a brand-new bond.”

While defeasance requires an upfront outlay of $5.75 million, the city stands to realize about $4.3 million in present value savings.

State lawmakers extended the earned income tax indefinitely and the local services tax for another 10 years, after which the city will retain half of the LST taxing power for five years.

Taxing powers under Act 47 enable distressed cities to assess these levies above state limits. An elevated LST shares the burden with non-residents, serving as a de-facto commuter tax.

The glut of tax-exempt property, a dynamic at many state capitals, “is more extreme here,” Papenfuse said. As the relatively small capital of a large state, roughly half the city’s property is tax-exempt, and the city’s poverty rate is nearly 30%.

“The linkage of the extension of the taxing authority to refinancing debt is a good way to frame the plan,” municipal bond analyst Joseph Krist said. “This is a way for the state to help out without additional cash, especially since it’s the local elected officials asking for the authority. On the political side. It's a win-win.”

While Harrisburg leased its municipal parking system to a private operator under a 40-year deal as part of the recovery plan, Moody’s Investors Service on Nov. 23 downgraded to junk-level Ba2 from Baa3 the Pennsylvania Economic Development Finance Authority’s Series 2013 parking system revenue bonds.

Proceeds from that bond sale helped pay down Harrisburg’s debt.

Moody’s cited “very narrow liquidity for the project as a whole,” with complete dependence on the commonwealth's monthly lease payment. One month earlier, Fitch Ratings lowered the bonds to BB-minus.

Harrisburg, like other cities, is coping with the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic. The city’s 13% positivity rate earlier this month was higher than 91% of U.S. cities. “That’s off the charts,” Papenfuse said.

The hiring of Connelly as an outside fiduciary advisor with an independent voice, through what Papenfuse called a “thorough” request for proposals process, marks another break from the past. The city pays Connelly on a per-hour retainer.

“Harrisburg, historically, and one of the reasons we ended up in the debt crisis that we did, had a lot of financial advisors that basically were paid based on the deals,” Papenfuse said.

“For instance, they’d enter into a swap deal or something regarding the school district, but the real reason would be to generate fees, which would then go into the general fund to purchase artifacts and other ulterior motives.”