“I said to my friend Jack Lew that we will take Puerto Rico into the eurozone if the U.S. takes Greece into the dollar union.”

German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble, July 9, 2015

In the eight months since Schäuble teased U.S. Treasury Secretary Jack Lew over Puerto Rico’s relatively small debt crisis, it’s become clear to some analysts that the German official may have underestimated the similarities to Greece’s debt debacle.

True, Greece’s debt is about 5.7-times the size of Puerto Rico’s and its economy is worse in terms of unemployment. Yet Puerto Rico’s worsening debt situation echoes Greece’s deterioration in 2010. Analysts who’ve followed Greece see some lessons for the U.S. as lawmakers in Congress try to gain control and avoid a protracted crisis in the Caribbean territory.

According to Anna Gelpern, fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a key lesson is that it’s up to the central power – in Puerto Rico’s case the U.S. – to take decisive action earlier in the process.

As Puerto Rico started missing payments last year, its attempts to restructure debts stalled in the courts. The debate continues in Congress over legislation to create a control board over the island’s finances, and whether to grant bankruptcy authority to the territory.

The risk, according to Gelpern, is that Puerto Rican suffering will worsen as long as a solution is delayed.

“The lesson of the Greek debt crisis,” she said, “is that the costs of dithering at the center fall on the periphery.”

History of Greek Debt Crisis

Greece was among the 12 members of the European Union that rolled out the use of euro notes and coins as currency at the start of 2002.

Greece’s economy generally did well in the following years, with inflation-adjusted gross domestic product growth rates near or above 5% in 2003, 2004, 2006, and 2007, according to the National Statistical Service of Greece.

Greece had been running budget deficits from 3% to 7.5% since 1999.

The Great Recession initially hit Greece as hard as most other European nations.

When a new Greek government took the reins in early 2010, it announced that earlier governments had been dishonest about the size of the 2009 deficit and the total amount of debt Greece owed. As the government revised these figures, lenders became concerned about Greece’s ability to pay back its debt and demanded higher yields.

In April 2010 ratings agencies dropped Greece to speculative grades. In its efforts to raise money to finance deficits and pay off maturing bonds, Greece was largely cut off from the private bond markets.

Since Greece owed the majority of its money to private sector banks and Europe was still struggling to emerge from the recession, there was widespread concern that a Greek repudiation of its debt could lead to a financial crisis in Europe. Other European nations were then also struggling with weak economies and high debt levels. Observers were concerned that a default in Greece would have a domino effect throughout Europe.

Greece had to turn to official European sources for the first of what so far have been three bailouts. In May 2010 the European Commission, European Central Bank, and International Monetary Fund (“troika”) approved a 110 billion euro ($123.2 billion) loan. This was conditioned on Greece cutting public sector jobs, slashing pensions, and raising taxes. Greece raised its value added tax consumer tax to 23% from 19%.

A year later, in response to a deep downturn in Greece, the government sought another bailout. In February 2012 troika agreed to loan the government 130 billion euros more.

At the same time Greece made a debt exchange, insisting that private borrowers accept a loss in face value on their debt and an extension of debt maturities. This haircut has been alternately reported as being 53% to 75%.

Superficially, the restructuring cut 137 billion euros from Greece’s 368 billion euro debt, according to Bloomberg. However, Greece borrowed an additional 78 billion euros from the European Union and the IMF to recapitalize domestic banks and pension funds that couldn’t handle the restructuring. Meanwhile it continued to borrow money from another EU/IMF rescue fund.

With the economy’s continued contraction, the debt restructuring only cut debt as a percent of GDP to about 151% from about 182%, according to the IMF.

Greece’s GDP declined 26% to 2014 from 2008. Its unemployment rate rose above 20% in late 2011 and reached about 28% in 2013. While it has since slipped a bit, it is still near 25%.

Tiring of the deepening austerity and disastrous economy, Greeks elected the left-wing Syriza party in December 2014 elections. It formed a government promising to renegotiate the terms of Greece’s agreements with the troika.

However, the troika offered an even tougher plan in June than it had after Syriza came to power. Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras called for a referendum on the plan on July 5, 2015. While the majority of voters voted no, a few days later Tsipras accepted the plan. This included more lending in exchange for more austerity.

As of mid-March 2016 the Greek government had 355.6 billion euros, equivalent to $398.72 billion, in debt.

Comparisons With Puerto Rico’s Debt Crisis

In both Puerto Rico and Greece gross national income per capita is about 50% of their related union’s average, according “Puerto Rico and Greece: A Tale of Two Defaults in a Monetary Union,” an article by German economist Daniel Gros. Greece’s “union” is the European Union and Puerto Rico’s is the United States.

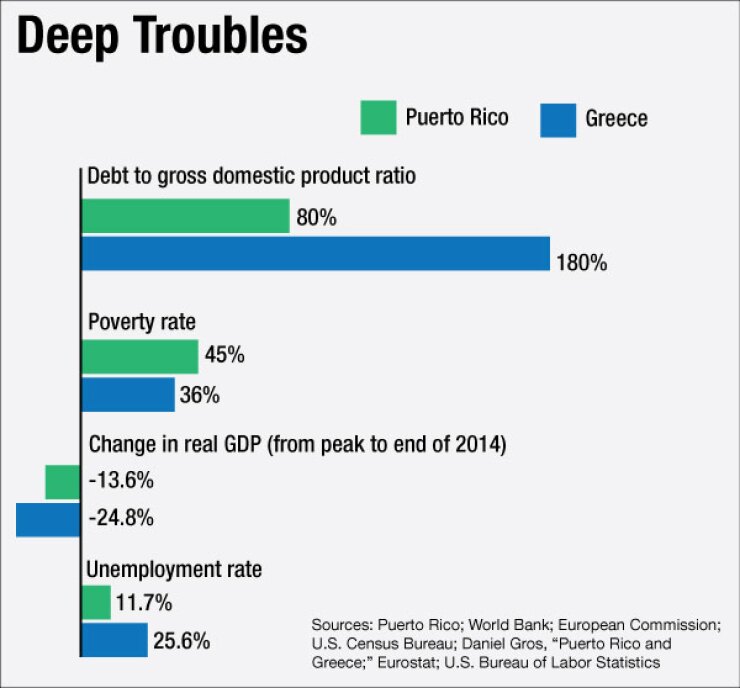

As of 2014 Puerto Rico’s poverty rate was 45%, compared with 36% in Greece, according to Gros, whose article appeared on June 18, 2015, on the Centre for European Policy Studies web site. Still more different is gross national product per capita, which in Puerto Rico is 78% that of Greece.

The unemployment rate is one of the biggest economic differences between the areas. Puerto Rico’s unemployment rate peaked at 16.9% in 2010 and stood at 11.7% in February. Greece’s unemployment rate peaked at 27.7% in 2013 and is still near 25%, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Despite this difference, the portion of their residents 18 years or older who hold jobs were very similar in the most recently available statistics: in Puerto Rico it was 35%, while in Greece it was 36%, according to Gros.

Greece’s ratio of government debt to GNP, 180%, is worse than that of Puerto Rico, 80%, according to the European Commission and the World Bank. The latter figure includes all Puerto Rico’s public sector debt.

Legal and political conditions also are comparable.

Neither Puerto Rico nor Greece has its own currency, so neither can boost its economy by devaluing its currency, said David Madden, market analyst for IG in Britain. On top of this monetary integration, there is also financial integration, in that people and entities outside each area hold a large portion of the debt, Peterson Institute’s Gelpern said.

While Puerto Rican banks are insured by Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., Greek banks lack any similar form of insurance. However, the Bank of Greece provides Greek banks easy access to liquidity, Gros said.

Among the more pronounced differences are that Puerto Ricans can migrate to the United States and reside there indefinitely. European Union rules are much tighter for migration between nations. This has left Puerto Rico with a shrinking population since 2005. Greece’s population has been relatively level in the last few years.

Some analysts have said Puerto Rico’s population contraction is a negative for its economy. However, emigration can also remove unemployed people from the island, some of whom were drawing commonwealth government resources.

Another difference is that while Puerto Rico has been part of the United States for more than 100 years and has used the dollar the whole time, Greece has only been fully using the euro since 2001, Gelpern said.

That has fueled concern that a disorganized Greek default would lead to an end to its use of the euro and a return to its old currency, the drachma. European leaders have worried that if Greece defaulted and withdrew from the euro, other European states would follow and the whole euro project would fall apart along with Europe’s economy, Madden and Gelpern said.

By contrast, no one thinks that a Puerto Rico default, no matter how broad or permanent, would lead to the end of the U.S. dollar or be a major threat to the U.S. economy, Gelpern said.

A final major difference is that Puerto Rico may have a framework to restructure its debts, Gelpern said. While Greece has no such framework, Puerto Rico is battling in U.S. Congress and the courts for authority to file for protection under Chapter 9 of the bankruptcy law.

In 2010 private banks held a substantial portion of Greece’s sovereign debt. In the years that followed much of this debt was transferred to the European Central Bank and the IMF. Europe’s leaders have been much less open to these institutions potentially taking haircuts than to having private holders take them.

A final key difference is that while Greece has been largely locked out from borrowing in the private capital markets since April 2010, Puerto Rico only lost access in the summer of 2015, when Gov. Alejandro García Padilla declared the island’s debts “not payable” at the prevailing economic growth rates.

Because Greece has been in open debt crisis longer than Puerto Rico and because of the similarities with the island’s government, the European Union’s mistakes may hold lessons for how Puerto Rico’s debt crisis should be handled.

Lessons for Puerto Rico and its Debt Holders

One of the lessons of Greece for Puerto Rico is that one has to be patient, said Matt Fabian, partner in Municipal Market Analytics.

Greece’s debt crisis has continued for at least six years with unemployment remaining high, debt levels elevated, and the economy in depression.

Gelpern said Puerto Rico isn’t condemned to repeat this history. The troika’s lack of decisive action early in the Greek crisis has prolonged the Greek people’s pain. Instead of taking wise action, she said, the authorities “kicked the can down the road.”

The IMF’s continued lending to Greece since the start of this decade may have merely extended its debt problem, Fabian said. Greece should have received an early write-down on all of its debt, said Stephen Gross, assistant professor at New York University. The “policy of a haircut for creditors was pursued to a certain extent in the Greek case, although only for some creditors, and only too late in the game,” he said.

Another lesson of Greece has been that massive austerity doesn’t work, Gross said. Even the IMF has accepted that its earlier austerity prescription was too much.

“What happened was that GDP declined faster than Greece’s overall debt, and therefore Greece’s debt-to-gross-domestic-product ratio has actually increased.” Moderate austerity measures would have had a better chance of reducing the debt, he said.

Fabian said debt problems are complicated and their resolutions require paying attention to more than just the debt.

Gelpern agreed, saying that a broad vision for Puerto Rico’s economy has yet to emerge. “This is very disconcerting,” she said.

“What Greece needs (with foreign help and by mobilizing idle domestic resources and the human capital in the diaspora) is to improve business environment, tackle endemic corruption, improve tax collection by tackling tax evasion and closing loopholes, and cut down on red tape,” Elias Papaioannou, professor at London Business School, said in an email.

There needs to be a reorganization plan, Gelpern said. There is a history of tax breaks for sectors in Puerto Rico coming and going, she said. Instead, there should be something durable that would also be widely perceived as durable.

While Washington must act decisively, it must be careful about a control board, Gelpern said. “One has to step very gingerly because of the colonial history.”

The prioritization of Puerto Rico’s current different forms of debt is unclear, she continued. As things stand, each creditor has an idea about how they can collect more than another creditor group. Any debt restructuring must simplify the creditor claims significantly.

A strong federal legislative solution for Puerto Rico would be best, Gelpern said. However, she was pessimistic this will happen. There are legally viable solutions, she said, but they may not be politically viable.