Mutual funds have emerged as the dominant source of selling pressure for state and local government paper in the new year as investors keep pulling out their money, forcing fund complexes to sell bonds into an already jittery market.

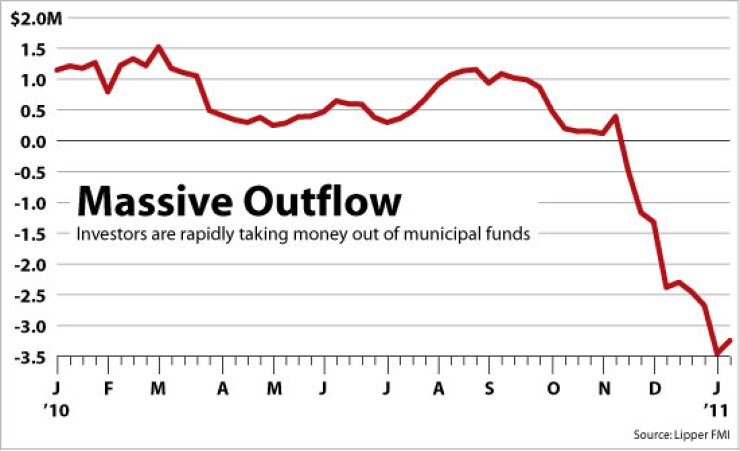

Investors have withdrawn $25.3 billion — a sum that exceeds the gross domestic product of Panama — from municipal bond mutual funds the past nine weeks, according to Lipper FMI. Funds that report their figures weekly posted a net outflow of $1.51 billion for the week ended Jan. 12.

Municipal funds are now reporting outflows at a rate of $3.25 billion a week, based on the four-week moving average. That’s well above any pace seen before the latest series of redemptions in the $478 billion municipal fund industry.

The spate of outflows has fund managers scrambling to sell municipal bonds at a time when dealers are already worried about the willingness of retail investors to digest long-term tax-exempt paper, breeding considerable volatility and weakness at the long end of the yield curve.

“On the trading desk we can see list after list after list of fund complexes trying to raise cash,” said Adam Mackey, who heads municipal fixed income at PNC Capital Advisors. “It’s certainly driving rates higher, because there’s not enough cash chasing too many bonds.”

Market participants have identified the culprit: headline risk.

The mainstream press has barraged the retail investor community with a ceaseless drumbeat of muni credit fear-mongering in recent weeks.

Meredith Whitney, who gained renown for her accurately bearish take on many banks in 2007 and 2008, brought the noise to a new level last month. She predicted “hundreds of billions” of dollars of losses due to municipal defaults on the CBS news program “60 Minutes.”

Although most professionals in the market dismiss such prognostication as overly dire, they say the well-publicized sentiment has clearly hampered demand. The stories have tarnished the municipal market’s reputation as a safe haven for investors.

“It had a large impact,” said Rick Taormina, a portfolio manager with JP Morgan Funds. “The headlines and some of the press around defaults, and the potential for sizable defaults, has prompted some responses more in fear than acting on the facts.”

Aside from headline risk, financial markets in general are tilting away from bonds and toward stocks as economic prospects brighten.

Municipals, though, are selling off more drastically than other types of bonds, particularly at long maturities.

The ratio of triple-A rated 30-year municipal yields to 30-year Treasury yields has spiked to an unusually high 111.6%. That compares with 107.3% at the end of 2010 and 100.3% at the end of the third quarter.

Most market participants cite mutual fund selling as the dominant factor pushing municipal rates up. After a very rough fourth quarter of 2010, 10-year triple-A tax-exempt yields are already up 20 basis points in 2011, and 30-year yields are up 43 basis points.

“There’s just so much supply being unloaded by mutual funds right now,” said a trader in New York. “There’s a lot of large blocks that we’re finding hard to absorb.”

Duane McAllister, who manages a $450 million intermediate tax-free fund for M&I’s Marshall Funds, said a good portion of the selling by mutual funds is due to both investor redemptions and the move by many funds to raise cash in anticipation of additional redemptions.

Mutual funds typically keep some percentage of their assets in cash to meet potential withdrawals.

According to the Investment Company Institute, municipal funds had 4.5% of their assets in cash at the end of November, compared with an average of 4.3% since the beginning of 2005.

When funds report outflows, McAllister said managers often build a greater liquidity cushion in case they face more redemptions. Because nobody knows the magnitude of forthcoming redemptions, he said managers try to play it safe and often do so by erring on the side of too much cushion. That selling pressures bond prices downward, sparking more redemptions, which in turn spawns more selling.

“For many funds it’s a problem of actual redemptions, but for all funds it’s the fear of redemptions,” McAllister said. “When redemptions occur, what the natural inclination to do is not to sit on your hands but to raise additional money with the anticipation that there’s more redemptions behind it.”

Mutual funds enjoyed a higher profile in the municipal market beginning in 2009. Investors equipped municipal funds with a record $69 billion in new money that year, and an additional $32.25 billion in the first 10 months of 2010, according to the ICI.

Those inflows were enough to absorb 13.2% of new municipal issuance during that time, an historically large share of new municipal issuance for mutual funds. From 1984 through the end of 2008, total municipal bond mutual fund inflows represented less than 3% of state and local government borrowing.

By the third quarter of 2010, mutual funds owned 18.7% of the $2.8 trillion municipal debt market — the highest share in history.

The constant flow of new cash into mutual funds in 2009 and early 2010 helped bolster the tax-exempt market, which was already enjoying lighter supply thanks to the Build America Bonds program. Light tax-exempt supply and heavy mutual fund inflows, along with low Treasury rates, helped shrink yields for 30-year triple-A tax-exempt bonds to their all-time low in August.

The technical support has reversed with a vengeance the past two months. Not only does the market face the prospect of dramatically more tax-exempt supply, the nonstop gusher of cash into mutual funds has reverted to a gusher of cash out of mutual funds.

“We had become very expensive, and that was driven really by the technicals,” Taormina said. “We’re seeing a reversal of those technicals.”

Between outflows and market losses, the municipal mutual fund industry has been hemorrhaging assets at an average clip of about $5 billion a week since the beginning of November.

The industry’s assets have already shrunk 3% this year, and 9.3% since their peak in October.

Forced to sell bonds into a troubled market, some of the biggest municipal funds are taking it on the chin.

The $29.8 billion Vanguard intermediate fund’s net asset value is already down 1% this year, and the $14.3 billion Franklin Templeton California fund is down 2.9%.”