The Rust Belt legacy lingers in dozens of Great Lakes economies that have spent decades struggling with sites contaminated by industrial pollution.

A $1 billion infusion of federal funding aims to help put that legacy to bed.

Milwaukee, Detroit and Cleveland are among 22 communities that will benefit from the new federal funding in the $1.2 trillion

The $1 billion will go to the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, an 11-year-old program that focuses on protecting and restoring the world’s largest freshwater system and its waterways.

The GLRI will use the new money to accelerate cleanup of 22 of 25 federally designated Areas of Concern in the U.S. around the Great Lakes that the government says have seen “significant impairment of beneficial uses…as a result of human activities at the local level.”

Polluted with manufacturing and agricultural toxins, the shoreline and waterway sites are considered some of the most environmentally degraded areas in the Great Lakes region. Federal and local agencies have already spent decades working on many of the sites, and the new money will help fund a final cleanup that will bring “significant value to the local economies,” according to Moody’s Investors Service.

The money will mean a final push for years-long efforts by local governments to develop new neighborhoods out of vacant areas filled with beer cans and dead fish, as one Environmental Protection Agency official put it.

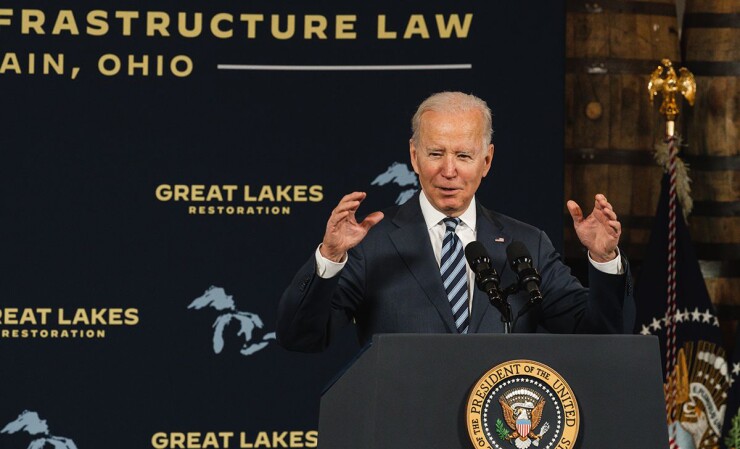

"It's going to allow the most significant restoration of the Great Lakes in the history of the Great Lakes,” President Joe Biden said in February when he visited Lorain, Ohio to tout the money. "We're going to accelerate cleanup of sites across six states."

It was in the 1980s that the U.S. first identified 31 Areas of Concern, including five shared with Canada, that needed comprehensive cleanup and restoration, said Christopher Korleski, director of the EPA’s Great Lakes National Program Office.

By 2010, the year the GRLI was established, only one, the Oswego River, had come off the list.

“Boy, that’s not an impressive record,” Korleski said.

Since 2010, five more Areas of Concern have been delisted.

Now, with the $1 billion of IIJA money in hand, the goal is to delist 16 of the remaining 25 by the end of 2030, with significant progress toward final cleanup on another six by the same time, Korleski said.

“I call it rocket fuel for accelerating our work,” Korleski said of the IIJA funding. “It’s a huge funding increase. We’re talking about cleaning up millions of cubic yards of contaminated sediment. It’s a very ambitious schedule but they’ve been around for way too long and we want to get them done.”

Since 2011, the GLRI has received around $340 million in annual appropriations from the federal budget. Of that, around $130 million was typically earmarked for the AOC program, Korleski said.

Nonfederal matches are required for the Areas of Concern work. The GLRI partners with a variety of entities, including local and state governments and private companies, for the funding, according to Korleski.

Transforming economies

The Milwaukee Estuary Area of Concern features roughly 11 miles of riverway around the meeting point of three Lake Michigan tributaries, the Milwaukee, Menomonee and Kinnickinnic rivers. The area sits right in the city, where factories and wastewater treatment plants left the area polluted with heavy metals, polychlorinated biphenyls and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

Officials have spent years cleaning up the site, and now condos, restaurants and new riverwalks dot the landscape, said Pamela Ritger de la Rosa, Milwaukee program director and staff attorney for Clean Wisconsin, an environmental advocacy organization.

Boating companies have popped up as kayaking and other water recreation became popular, and the city has even sponsored open water swims the last few years, she said.

“In Milwaukee, for a long time we turned away from our rivers and since the 1990s we’ve been turning toward the rivers and realizing the amenities they provide,” said Ritger de la Rosa, who sits on the Milwaukee Area of Concern citizens' advisory committee, which holds public meetings and seeks public input.

But major work remains to clean up the riverbanks, beaches and water, Ritger de la Rosa said.

Before the IIJA funding was announced, the city had to compete for a piece of the GLRI’s annual appropriations with other Area of Concern sites, she said. The new GLRI money lift that pressure and means a promised final cleanup by 2030.

“This is a huge deal and a really important investment in cleaning up our waterways and making them safer for recreation and fish and plant habitat,” she said.

The Milwaukee cleanup echoes work being done in cities like Cleveland, said Moody’s Investors Service in a March 23 brief on the new federal funding.

In 1969, the notoriously polluted Cuyahoga River caught fire. The river was named an Area of Concern in 1987, and since then federal and local agencies have worked to clean up the site.

In 2019, 50 years after the fire, the EPA declared the fish in the Cuyahoga River safe to eat, Moody’s analyst Ryan Patton wrote in the report.

The new GLRI money will complete the habitat restoration at the river with an aim of delisting it by 2030.

“As the city’s economy has diversified away from its industrial legacy, restoration of Lake Erie and connecting waterways has spurred development focused on the amenities provided by the lake,” Patton wrote. “Similar transformations are taking place in Chicago, Detroit and Milwaukee.”

In an interview, Patton said the Great Lakes and its waterways are a key credit factor in the regional economy.

“The Great Lakes are a great asset because they provide drinking water but also because they bring a significant amount of economic activity,” Patton said. “It’s a long-term trend, but there’s been a lot of focus on developing the lakefront and developing rivers that provide amenities."

Economic output in the Great Lakes represents more than 15% of the national GDP, Patton said.

“Maintaining those benefits requires some continued costs, and by investing dollars in those environmental protections, it helps protect the local governments from economic and fiscal costs that could arise if something happens.”

The legacy pollution, as well as other challenges like invasive species, are considered natural capital risks in the rating agency’s ESG methodology, said Moody's analyst David Levett.

“There’s a lot of investor

Moody’s and the EPA both cite a 2018 University of Michigan study that found every GLRI dollar produces $3.35 of economic activity and more than $4 in older industrial cities like Buffalo and Detroit.

“It could be an old abandoned waterfront area filled with beer cans and dead fish – no one wants to go there,” Korleski said. “If you take these areas and clean them up, and restore the water quality, then people do want to come back and the cleaned-up areas turn into revived economic centers,” he said. “As I like to say, if you clean it, they will come.”