As an overflow crowd gathered for a public hearing in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene neighborhood, New York City Transportation Commissioner Polly Trottenberg acknowledged the enormity of the pending Brooklyn-Queens Expressway reconstruction.

“This is not a project we relish,” Trottenberg told reporters at the Ingersoll Houses Community Center on Myrtle Avenue. "This is not an easy one for any of us and we recognize that.”

The city is presenting options for its $3 billion-plus overhaul of a 1.5-mile stretch of Interstate 278 from Atlantic Avenue to Sands Street, near the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges. Speaking Thursday night before the first of several public hearings, Trottenberg called it “obviously one of the most difficult and challenging infrastructure projects not only in New York City but probably in the United States right now.”

The scenarios for undoing a 1940s-era triple-cantilever structure, a layer-cake concoction of Robert Moses, New York's mid-20th-century

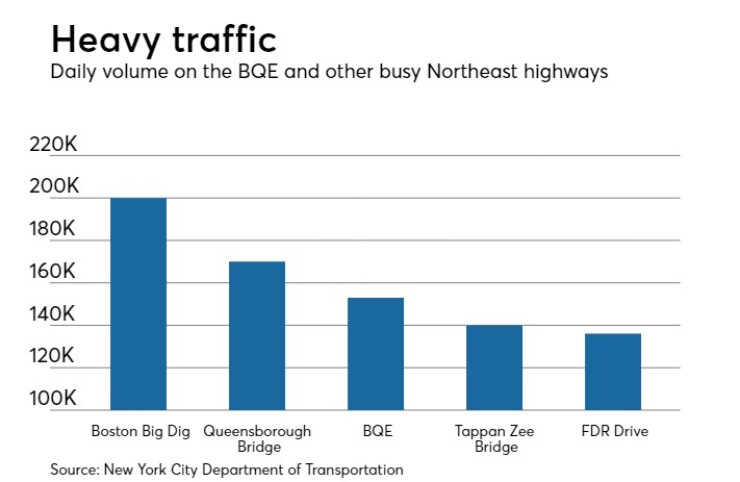

Still, according to Trottenberg, the work is critical. The road carries roughly 153,000 vehicles daily, including 25,000 trucks. Without the undertaking, she said, the city would have to exclude trucks by 2026 and shut the stretch down altogether by 2036.

Construction could begin in 2020.

The city has the opportunity to tap into its limited use of design-build project delivery, which could cut costs, save time and open the door for further such use should the state legislature grant it.

Other project dynamics include a domino effect on mass transit and its related capital needs, and the possible tolling of East River bridges through a state or city congestion-pricing plan.

Community emotion is strongly at play, given the expected loss of the iconic Brooklyn promenade -- and its panoramic views of the harbor and lower Manhattan -- for up to six years through the construction of a temporary elevated highway under one scenario. That approach calls for an improved promenade at the end.

Transportation-wise, the borough is already on edge, given the pending shutdown of L-train subway service while the Metropolitan Transportation Authority completes Hurricane Sandy-related damage to the Canarsie Tunnel, which connects Manhattan.

The promenade, which sits above two layers of highway, is part of the structure itself. While also 70 years old, it has been a magnet for homebuyers in its tony Brooklyn Heights neighborhood.

“Look, I’m sympathetic to ‘save the promenade.’ I love the Brooklyn promenade,” Trottenberg said. “[But] the promenade and the two levels of highway are one structure. So if we repair it, we need to repair it altogether.”

The city expects to trim costs through design-build under which one entity, often a joint venture of infrastructure firms, works under a single contract. While 43 states have it fully in place, New York State has used its only in limited projects such as the Kosciuszko Bridge, further up I-278, and the Mario Cuomo (nee Tappan Zee) Bridge, 35 miles north.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Mario’s son, granted the city selected use of design-build in March as the New York City Housing Authority crisis mushroomed. Targeted projects are the BQE, NYCHA properties and prison construction as the city prepares to close its Rikers Island facility.

Complexities make the project a natural for design-build as opposed to New York’s more standard design-bid-build, according to Roddy Devlin, a partner at Nixon Peabody LLP.

“[It’s] a key transportation artery that you can’t take risks with,” Devlin said on a Bond Buyer

Design-build is also more transparent, said Tanvi Pandya, the DOT’s senior program manager for the project. “You will be able to see things a little more fully cooked,” she said.

Pandya also warned that tight contracting parameters could stifle innovation. “We have to give them room to innovate,” she said. “If we give them a very narrow rebuild, it limits what they can do.”

Regional transportation advocates have called for tolling the now-free bridges across the East River as part of a congestion-pricing plan that can support billions of dollars in bonding for both mass transit and road repair. While such proposals have stalled in the state legislature, City Council Speaker Corey Johnson has suggested that the city could ride solo on such a plan.

“I would like to see what exactly is this traffic, how much of it is critical and how much of it is people avoiding the bus and single-use cars, such as Uber and so-forth,” said infrastructure expert Nicole Gelinas, a senior fellow with the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research.

Before a standing-room-only gathering on Thursday, DOT officials presented two scenarios for the BQE. They said the so-called innovative approach, at a cost of $3.2 billion to $3.6 billion and involving the temporary elevated highway, could finish the project in six years and with a more predictable price tag.

By contrast, lane-by-lane reconstruction could cost up to $4 billion, take more than eight years and pose cost and scheduling uncertainties. It would avoid dramatic effects on the promenade, but could worsen congestion for residents and drivers, even all the way to Queens and Staten Island.

The layer-cake structure was Plan B for Moses, a de-facto mayor of sorts who oversaw several city departments. After bulldozing neighborhoods in Carroll Gardens and Sunset Park, Moses wanted to force a six-lane highway through Brooklyn Heights, but he encountered heavy community pushback.

Hence the vertical structure, construction for which began in 1944. Repairs over the years have mostly involved patchwork.

“Robert Moses built this crazy, substandard highway years ago and the city has inherited it,” Trottenberg said.

Some speakers at Thursday’s meeting, which the DOT relocated to a larger venue at the last minute, worried that money would expire before promenade restoration. They also accused the city of breaking promises related to nearby Brooklyn Bridge Park development. Others discussed air quality, and a desire to move the project westward toward the water.

The DOT will continue with hearings throughout the fall. Next summer it intends to issue a request for qualifications – design-build legislation requires one no later than April 2020. It expects to draft a request for proposals late next year, after it drafts an environmental impact statement.

It must go through a National Environmental Policy Act process through 2020.