Last month, Chairman Patrick Foye likened the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s financial predicament to a four-alarm fire. On Wednesday, he called it a “once-in-a-hundred-years fiscal tsunami.”

Mixed metaphors aside, Foye’s message remains clear: The authority is in big trouble.

“An enfeebled MTA would stunt the regional recovery and create a depressing drag on job growth,” Foye said at Wednesday’s monthly board meeting.

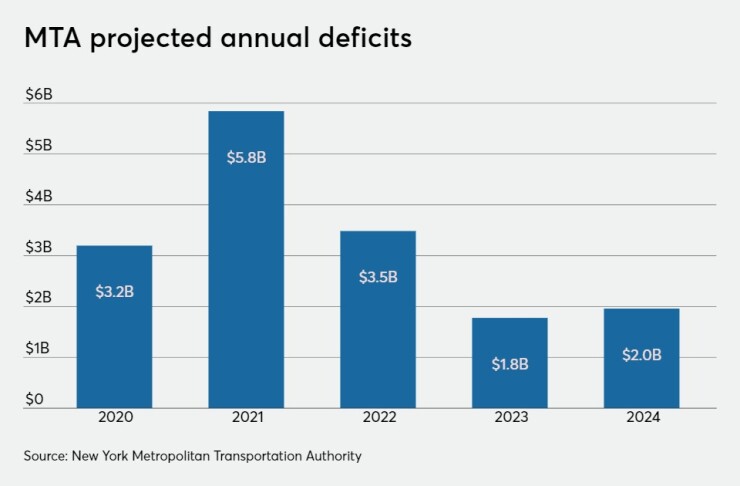

Even with further COVID-19 rescue aid, which the U.S. Senate is debating and is hardly a given, the nation’s largest mass-transit agency is staring at massive red ink, including a projected $16 billion deficit through 2024, and a vast range of immediate uncertainties that could include more rating downgrades.

The MTA will exhaust the $3.9 billion it under the federal CARES Act at the end of the month. It has requested the same amount in the HEROES Act, which the U.S. Senate is considering after the House of Representatives approved it.

Transit systems nationwide are seeking up to

“If we don’t get federal help, we are so screwed, bottom line,” board member Kevin Law said. “This is life or death for us."

Little or no aid from Washington could prompt a rash of doomsday moves, including deficit borrowing, which could further jeopardize its standing on Wall Street. Other options include service cuts; reductions and/or delays in the 2020 to 2024 capital program; fare and toll increases beyond the routine biennial hikes; and layoffs.

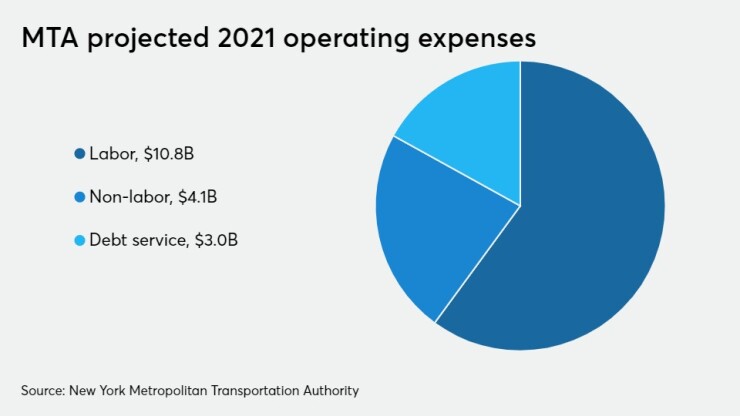

The MTA has projected a coronavirus-related hit of $14.3 billion for this year and next, or 41.4% of its operating budget. That includes plummeting fare and toll revenue largely due to stay-at-home and social distancing measures to combat the pandemic and reduced demand because of the weak economy, plus the loss of subsidies such as dedicated taxes and additional costs from cleaning the system.

Chief Financial Officer

The authority, which operates New York City’s subways and buses, two commuter rail lines and several interborough bridges and tunnels, is one of the largest municipal issuers with $46.2 billion of debt, including special credits.

It has received multiple downgrades since March, most recently July 7 when S&P Global Ratings lowered its primary transportation revenue bond credit to BBB-plus from A-minus, citing its mass transit enterprise ratings criteria.

“The state of the MTA borders on the catastrophic,” said Rachael Fauss, research director for the advocacy group Reinvent Albany.

The MTA expects to issue $500 million of Series 2020B-S transportation revenue bond anticipation notes and $600 million of Series 2020-D transportation revenue bonds in August.

According to data on the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board's EMMA website, a block of Series 2016B transportation refunding bonds maturing in 2025 that originally priced at 128.185 cents on the dollar and a 1.73% yield, sold to a customer Wednesday night at a price of 109.523 cents and a 3.043% yield.

Foye would not elaborate how the MTA would impose cuts, such as expansion, state of good repair or accessibility. “All of them are unattractive and unpalatable, but we’ve got to consider all of these things," he said.

Last-resort deficit borrowing could come in the fall, Foran told reporters.

“If we do sell deficit financing, we’d have to pay for the deficit financing bonds,” he said. “Deficit financing just takes away from our capital program. It’s not a productive use of funds.”

The MTA also has various liquidity resources such as lines of credit, pay-as-you-go resources, the Other Post-Employment Benefits Trust, deferral of federal payroll taxes and the Federal Reserve’s

“However, these funds only provide a temporary funding ‘bridge’ to a permanent solution to the lost revenue and higher expenses, and these funds must be repaid or replaced,” Foran said.

Board members must vote on the $17 billion-plus operating budget in December. The MTA operates on a calendar year.

Congestion pricing for Manhattan’s central business district, which could provide $1.5 billion in capital funds annually, is on hold. The MTA and the federal government are stalled over an environmental review process.

“We’re still in limbo,” capital construction chief Janno Lieber said.

Also hovering is the memory of the dark days of the 1970s, when the city was broke, crime rampant and breakdowns and track fires marred subway travel.

“I think it’s clearly a five-alarmer, and my concern is that we don’t see the fire engines, nor do we see the plans on how to build them," board member Robert Linn said. “We don’t see a road map for survival.

“We see a continuing exit of terrific transit managers, which worries me tremendously," said Linn, a former New York City labor-relations commissioner. "We hear public discussions of org charts and once again hear criticism of the city’s homeless outreach efforts. Instead of grappling with the tough decisions, we see the same old battles between the governor and the mayor, the MTA and the city, the legislature and the city, the MTA and the board.”

Sally Librera, the MTA New York City Transit’s senior vice president of subways, is the latest departure. Her last day is Friday.

Ridership reached 2.2 million on subways and buses Monday — up 60% since early June — as the city began Phase IV of its reopening. Still, that’s far below last year’s daily average of about 7 million.

The board will meet next month, skipping its usual August break. The date will depend on “action or inaction from Washington,” Foye said.