Connecticut has begun its third month with no state budget, and with no common ground apparent between Gov. Dannel Malloy and lawmakers, cities and towns reliant on state aid are increasingly skittish.

The state legislature isn't expected to vote on a biennial spending plan until the week of Sept. 11, with an increase in the state sales tax one of the main sticking points, along with Malloy's attempt to shift one-third of teacher pension costs, or $408 million, to localities.

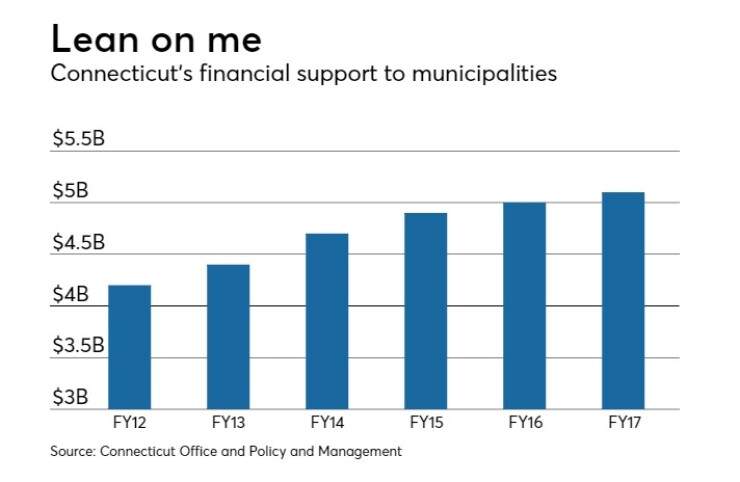

The Connecticut Conference of Municipalities on Wednesday objected to a report by Malloy's Office of Policy and Management that defended the state's track record in aiding cities. The report said municipal aid in Connecticut had risen by $1 billion, or nearly 21% over five years to $5.1 billion.

State officials "seem to have taken the 'let them eat cake' approach," said Coventry Town Manager John Elsesser.

Malloy admitted that he and lawmakers are still gridlocked.

“I don’t see that the House is anywhere near passing a budget that I could sign,’’ said Malloy. “Certainly everything I know about the budget that they’ve deliberated on over the past couple of weeks — means I would not sign that budget.”

Malloy has run the state by executive order since July 1, updating it on Aug. 18.

He said he would not allow a budget to become law without his signature, as then-Gov. Jodi Rell did in September 2009. “If you’re asking if I’m going to pull a Rell, the answer is no."

Moody’s Investors Service called Malloy's latest order a credit negative for local governments because it reduces total aid to municipalities by $928 million, or 38%, from 2017 funding levels and roughly $244 million from the governor’s June 26 order.

The order also reduces the largest source of state municipal aid, education cost sharing grants, by $557 million compared with the fiscal 2017 allocation.

Moody’s rates Connecticut’s general obligation bonds A1, while S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings assign A-plus ratings. Kroll Bond Rating Agency rates them AA-minus. S&P in July revised its assessment of Connecticut's institutional framework to strong from very strong.

Municipalities on edge range from 110,000-population state capital Hartford -- which seeks an additional $40 million in state aid and has hired a bankruptcy advisor -- to obscure, 1,700-population Scotland in eastern Connecticut, where officials say the community could dissolve by the spring should the budget impasse linger.

“We’re on a bare bones budget,” said First Selectman Daniel Syme. “We’re beyond bare bones; we are down to the bone marrow.”

According to Municipal Market Analytics, Connecticut local credit quality “runs the gamut” from triple-A rated Westport to state capital Hartford, whose bonds Moody’s and S&P Global Ratings have rated junk. Reserve fund buffers also vary greatly from 35.7% for Warren to minus-10% for West Haven, said MMA, which culled data from the Connecticut Mirror.

“Comparing these metrics gives us an idea of the degree of immediate flexibility each government available to address reductions,” said MMA. “Not surprisingly, the cities of West Haven and Hartford, are shown to have the least amount of flexibility.

Malloy said an additional report by his budget office will follow, containing information on the financial health of the municipalities by bond ratings, mill rates, fund balances and grand list changes.

The governor said the $5.1 billion in fiscal 2017 includes more than $3 billion annually in statutory formula grants and capital programs such as local school construction that can range between $600 million and $850 million annually.

Other examples of capital funding benefiting municipalities, he said, include housing, public libraries, open space land acquisition, brownfields, economic development and clean water.