CHICAGO — Chicago's school system is trying to avert a liquidity crisis through two short-term fixes to provide breathing room as it pursues long-term solutions to its pension and budget ills.

One was put on life support Tuesday not long after it was introduced. Chicago Public Schools had reached agreement with city and state leaders and Gov. Bruce Rauner to allow the district to push off to Aug. 10 from June 30 the deadline to make a $634 million teachers' pension contribution. The district expects to be in a better cash position in August due to tax and state aid payments.

On Tuesday, State Rep. Barbara Flynn Currie, D-Chicago,

Madigan said later in the day at a news conference the measure would be called again for a vote next Tuesday when the House reconvenes.

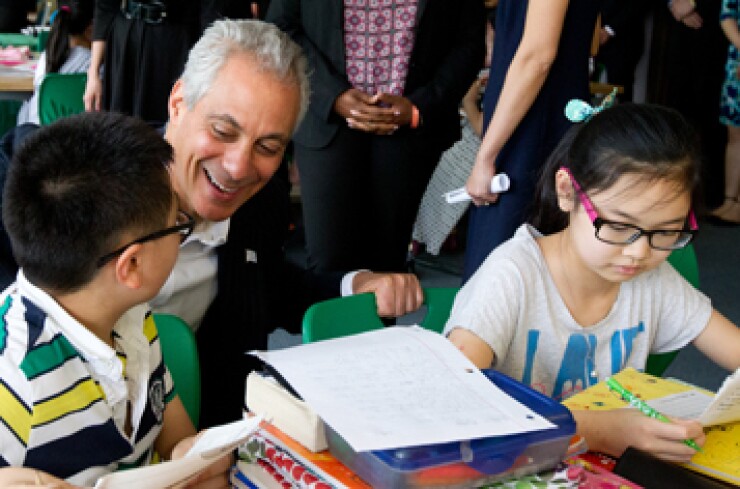

In the meantime, Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel's hand-picked school board is expected late Wednesday to approve $1.135 billion of short-term tax anticipation note and warrant borrowing.

The maneuvers would give the district short-term relief as it struggles to stay afloat, erase a $1.1 billion budget deficit, and tackle a more permanent solution, but they come with the risk of triggering fresh credit rating hits and further burdening the district's balance sheet over the longer term.

"The short term solutions are helpful at keeping the problems out of the short term," said Matt Fabian, partner at Municipal Market Analytics. "But at some point they have to find a bigger solution and will probably need a mix of new revenue, cuts, and a longer term deferral of their employer contributions." The district's fiscal 2016 payment rises to $688 million from $634 million this year.

"At least there's movement and planning and constructive dialogue," which are all positive signs, Fabian added.

The borrowing plan comes with the school system's fiscal prospects growing bleaker heading into the new fiscal year July 1, illustrating the financial strains that drove Moody's Investors Service to drop the school board's rating on $6.2 billion of debt to a speculative-grade Ba3 in May.

Longer term pension relief remains elusive. The district wants some combination of pension reforms and compensation for what local officials call the dual taxation of Chicago residents who support both local and state teachers' pension funds, or a merger with the state teachers' fund.

The district is delaying release this month of its next budget in the hope that it can still secure long-term help from state lawmakers if freshman GOP Gov. Bruce Rauner and General Assembly's Democratic majorities end their budget stalemate.

The pressures are reaching a critical point, according to a

"In just two years, CPS has paid more than $1 billion for pension costs and while the district has made every effort to balance past budgets without touching classroom spending, if Springfield does not take action, that may no longer be the case," Jesse Ruiz, vice chair of the school board and interim chief executive officer, said in a statement seeking to make the district's dire case for help.

The Borrowing Plans

One item on the Wednesday school board agenda would authorize $935 million of tax anticipation warrants and notes and the other would authorize $200 million of tax anticipation notes. Officials said the borrowing would be done in what they referred to as new short-term credit lines. The $200 million line would help the district cover remaining expenses before the fiscal year closes June 30.

CPS is contemplating using the larger line, as it has in previous years, to cover cash flow fluctuations through fiscal 2016. District officials could not provide any additional information on the proposed borrowing.

In addition to the line of credit, CPS warned it might still need to cut spending with reductions that could impact classrooms and academics. Ruiz said the recent report by Ernst & Young shows CPS is running out of cash underscoring the need for the short-term borrowing "to enhance cash flow management."

The proposed move resembles other short-term tactics, like scoop-and-toss bond restructurings and draining reserves, the district has relied on in recent years to erase growing budget gaps. They contributed heavily, along with its pension obligations, to the district's credit rating deterioration.

In addition to its $9.5 billion of unfunded liabilities, the district must negotiate a new teachers' contract to replace the one that expires this month and faces the threat that banks could demand $228 million in interest-rate swap termination payments due to its credit deterioration. The district has limited flexibility; its property tax levy is limited by state-imposed caps and it has already closed 50 schools and cut spending by $740 million over the last four years.

The use of a warrant structure represents a weaker form of security as a singular pledge is assigned, said Richard Ciccarone, president at Merritt Research Services LLC, adding he sees the use of short-term fixes "as symptoms of the most severe crisis they've had since the late 1970s."

In 1979 the school district was attempting to roll over existing notes, triggering a cut in its short-term ratings that killed the borrowing. After negotiations, a group of local banks, led by the former Continental Bank, aided the district by each taking a piece of the notes, recalled Ciccarone, who worked on the agreement early in his career.

That led to creation of a state oversight panel that controlled CPS finances and issued debt on its behalf until control was handed over to former Mayor Richard Daley under reform legislation in 1995.

Ernst & Young

The analysis CPS commissioned from Ernst & Young paints a grim picture of the district's near-term liquidity and long-term structural maladies.

The district has been running a structural deficit for the last four years of about $500 million, mitigated by the use of non-recurring revenues and past pension payment deferrals.

Without state intervention or other long-term revenue help, the system is on track to post deficits of more than $1 billion annually, reaching $5.4 billion in fiscal 2020 with a bigger portion of the budget being consumed by debt service and pensions.

A $500 million decline in available general state aid by fiscal 2020 is expected due to rising debt costs and falling capital development board grants.

"While forecasted deficits continue to be a major concern, CPS faces a $1.9 billion cash shortfall by the end of fiscal 2016 and absent immediate action, an imminent liquidity crisis," the May 22 report warns. "Based on current estimates and absent immediate action, CPS may not have sufficient liquidity to fund its upcoming obligations."

The report recommends "a combined approach" that includes new revenue sources, aggressive cost-cutting measures and legislative support.

The report lays out a series of options for addressing the district's budget gaps. The district could realize savings of $200 million to $500 million through some combination of pension reforms, fund consolidation, or increased state help. The district could seek additional aid, construction funding support, cut spending, and raise employee contributions to healthcare to save hundreds of millions more.

The report also suggests two new taxes. One is a capital improvement tax that could be levied with city approval and generate $50 million and the other is a new property tax levy to raise between $100 million and $400 million and replace the state aid that now goes to cover debt service. Many market participants and observers already expect the city to raise property taxes to cover its own rising pension costs.

Debt service and pension unfunded obligation costs are projected to ramp up consuming an additional $1.8 billion of revenue by fiscal 2020, representing 27.5% of general state aid, up from 16.1% last year. The district is curtailing new borrowing but has warned expenditures will be insufficient to meet CPS' needs.

The report was compiled for district's "sole" use and cautions that others should not rely upon it, with a note that it the analysis was not prepared in conjunction with any debt issuance. It also discloses that the information primarily came from the district and school documents and information from other sources were not independently verified.

The deficit projections for fiscal 2016 and the estimate of a $300 million fund balance this year mirrors information in the district's most recent offering statement, but the consultant's report paints a more dire situation as it's forward-looking.

The board in April - prior to the Moody's downgrade to junk -- sold $300 million of GOs to take out short-term paper that also carried a pledge of state aid. Investors demanded steep penalties. The top yield of 5.63% on a 25-year maturity landed 285 basis points over the Municipal Market Data's triple-A benchmark.

Prior to the sale, the district was hit with several multi-notch downgrades that triggered interest-rate swap termination events negatively valued at $228 million. The bank counterparties have not demanded payment and the Ernst & Young report noted that negotiations are ongoing with banks.

Rauner has suggested that Chapter 9 presented a good option for the financially beleaguered district, though such a bankruptcy is not currently possible in Illinois law. The district also disclosed a federal probe into the role CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett played in a no-bid contract at her previous employer. She later resigned.

The school board carries ratings of BBB-minus with a negative outlook from Fitch Ratings, an A-minus with a negative outlook from Standard & Poor's, and BBB-plus with a stable outlook from Kroll Bond Rating Agency. Moody's assigns a negative outlook.