SAN FRANCISCO — California, traditionally the largest issuer of municipal bonds in the country, is set to constrain its bond sales for another year, tightening supply to one of the hungriest markets of all time.

Gov. Jerry Brown has proposed only $5.2 billion of general obligation bond sales this year after issuing nearly $5 billion last year, which was down by half from 2010 and only about one-fourth of what it issued in 2009.

In 2011, California fell to the third-largest issuer by volume from first place the previous year. That means less supply in a market that has seen yields continually hit all-time lows since the beginning of the year.

“Without the [California] state financing, you don’t have a good source of raw materials to drive portfolio performance,” said Tom Spalding, a fund manager at Nuveen Asset Management. “We expect the same thing to take place in 2012.”

As investors search for safe returns, municipal market issuance has been curtailed amid weaker government revenues. This has helped bond yield indexes to fall to historic lows.

Yields on bonds maturing in 15, 20, 25, and 30 years all set new low records on Wednesday, according to Municipal Market Data, while the 10- and two-year municipal yields held just off their lows.

The lack of supply has a particular impact in California, where demand is partly driven by the state income tax. The governor has also proposed an initiative for the November ballot to temporarily raise income tax rates on the wealthy.

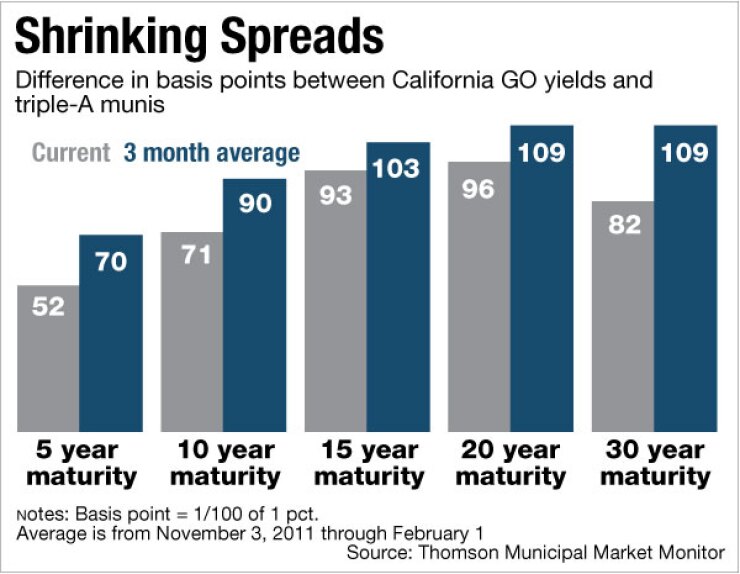

“It looks like it is going to be the same scenario that we have been working with the last year or so, and that is there are just a lot buyers looking for less paper,” said Kelly Wine, executive vice president of R-H Investment Corp., a broker-dealer in Los Angeles. “The spreads have tightened to extreme levels. I can’t remember when I have ever seen things this compressed.”

The difference in yield between a 10-year California general obligation bond rated single-A versus a triple-A bond had tightened to 71 basis points as of Wednesday compared to 90 basis points on average for the last three months, according to Thomson Reuters.

Over the last 10 years, California has issued $87 billion of GO debt. From 2007 through 2010, the state sold $53.8 billion, according to Thomson Reuters.

Last year, California was the third-largest muni issuer, selling $4.9 billion. In 2010, it was the largest, selling $10.5 billion.

This year, Brown has outlined a spring sale of $2.3 billion and a fall sale of $2.9 billion. The state also will sell revenue anticipation notes to help buffer cash shortages during the year.

The drop in sales is part of Brown’s priority to tackle the state’s “wall of debt,” including the amount of the general fund dedicated to debt service.

To accomplish that goal, the administration has been pushing departments to use unspent bond proceeds, if possible, before selling new bonds, according to H.D. Palmer, a spokesman for the Department of Finance.

“We will still have a need to go out to market for bonds,” Palmer said. “But at the same time, one of the administration’s priorities is getting those bond proceeds spent down and put to work so that they are not sitting idle.”

The state did not issue any new bonds last spring because it had enough bond proceeds on hand to meet cash needs.

Palmer said excess proceeds were partly a result of the state’s decision in 2008 during the recession to move away from funding projects from a bond money pool, and toward direct financing.

Another reason for holding off on bond issue cited by many observers, including rating agencies, is the state’s rising debt service costs.

“The debt service to support a new, large bond offering or program would increase the fixed-cost portion of the state’s budget. Higher fixed costs only make any future cuts that much more of a strain on the remainder of the budget,” said Standard & Poor’s lead California analyst Gabriel Petek. “These are the difficult policy considerations that have credit implications, but the nuance is that they have more than a fiscal bottom line.”

As part of this year’s $92.6 billion spending plan, Brown has earmarked $5.4 billion, or 5.6% of general fund revenue, for annual debt service. In fiscal 2003, debt service was just $2.1 billion and 2.9% of revenue.

The state had $82.6 billion of general fund-supported debt outstanding as of the end of June, according to the treasurer’s office.

The rising debt-service burden on the general fund is expected to continue through the end of the decade, according to the Department of Finance, peaking at $7.5 billion in fiscal 2020.

Treasurer Bill Lockyer has been warning for years about the rising debt service costs, saying the state needs to identify other funding streams for capital needs.

“We have massive infrastructure needs in California on a statewide basis and there is no way that we can fund all of those needs with the general fund,” said Lockyer spokesman Tom Dresslar.

Those infrastructure needs have driven the state’s voters to authorize more than $100 billion of bonds since 2000.

Lawmakers are also battling over two new major infrastructure projects that require massive amounts of bonding — an $11 billion water deal that is slated for the November ballot and $9 billion of bond funding for high-speed rail that voters approved in 2008.

Both programs are facing opposition that would like to see them delayed, reduced or quashed, which could limit sizeable bonds sales in the near future.

“There is no question in many people’s minds that we have overcommitted to bonds,” said Larry Gerston, a political science professor at San Jose State University. “There is no Santa Claus when it comes to California’s infrastructure.”

Gerston said issuing bonds is the easier political way to fund infrastructure because the other option is to raise taxes.

S&P and Fitch Ratings each assign California GOs an A-minus. Moody’s Investors Service rates them A1, two notches higher.