WASHINGTON — Eight Wall Street and regional banks and broker-dealers have been accused in a whistleblower suit of “widespread fraud and collusion” in connection with remarketing the variable-rate demand obligations of state and local issuers in Illinois.

The suit was

As a result, these firms collected tens of millions of dollars of remarketing fees each year from issuers in Illinois, without really providing remarketing services, the suit claims. The banks also collected fees from issuers for serving as liquidity providers for the VRDOs, when such services were rarely, if ever, needed, the suit claims. The high rates the firms allegedly set ensured the VRDOs would remain as holdings of tax-exempt money market funds, some of which were owned or managed by these firms, according to the suit.

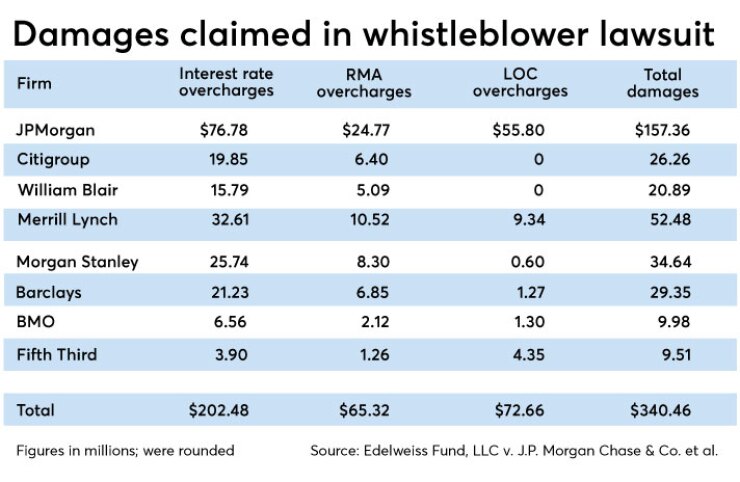

The suit claims the eight firms overcharged issuers on: interest rates by $202.48 million; remarketing agent fees by $65.32 million; and letter of credit fees by $72.66 million for a total of $340.46 million in estimated damages.

The suit seeks treble damages and penalties from the firms.

Spokespersons for the firms either declined to comment or could not be reached for comment. Some said they were aware of the complaint.

Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan was notified of the suit and asked if the state wanted to intervene which is permitted under such complaints. "The state did not intervene," said Madigan spokeswoman Maura Possley. On whether the state supported the lawsuit or intended to participate, Possley would say only: "We're monitoring the case."

Gov. Bruce Rauner's administration did not have an immediate comment on the lawsuit. Representatives of major Illinois-based issuers — the Illinois Finance Authority, Chicago and the Illinois State Toll Highway Authority — said they weren't aware of the suit.

The suit, which has taken the firms and market participants by surprise and is likely just the start of such whistleblower suits and enforcement actions, comes to light as analysts are predicting an upswing in VRDO issuance because of rising interest rates, as well as the municipal market’s loss of advance refundings and the drop in tax corporate rates under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

Several municipal market participants, asked generally about the potential for abuse in setting VRDO rates before the suit was made public, said they would be surprised to see wrongdoing. VRDO rates must be reset at a level necessary to market them at par. Also VRDO rates are transparent. Remarketing agents report rate resets to the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board’s Short-Term Obligation Rate Transparency (SHORT) System and MSRB makes them available on its EMMA website.

The suit was originally filed on Aug. 28, 2014, then voluntarily dismissed and refiled in the Cook County circuit court on Jan. 10, 2017, under the Illinois False Claims Act on a sealed basis. It was unsealed Tuesday as the banks and broker-dealers charged were served with the complaint.

Edelweiss is a Delaware-registered limited liability company that was incorporated on April 29, 2014, specifically to pursue this litigation. The complaint says Edelweiss’ principal has more than 20 years of experience advising municipalities and other clients on issuing securities, particularly VRDOs and other types of municipal bonds. Other than that, little public information about the company exists.

The lawsuit says the principal at Edelweiss uncovered the alleged wrongdoing while working in the industry and after performing “an extensive forensic analysis of the interest rates and other market data” for VRDOs issued in Illinois and other states that were remarketed by these banks and broker-dealers over a roughly four-and-a-half-year-period from April 1, 2009, through Nov. 14, 2013.

Michael Lissack

Edelweiss’ expert consulting witness is none other than Michael Lissack, the former Smith Barney banker who helped the government win hundreds of millions of dollars — and reaped tens of millions of dollars himself in the process — from filing whistleblower lawsuits against Wall Street and other firms in 1995 over charges they engaged in yield-burning. The firms overpriced the securities they sold issuers for advance refunding escrows, thereby lowering or burning down the investment yield so it would not exceed the bond yield and generate impermissible arbitrage for the issuers.

Lissack’s action led the Securities and Exchange Commission and NASD (now Financial Industry Regulatory Authority) to take enforcement action against many banks and broker-dealers over yield burning that agreed to pay tens of millions of dollars to settle charges.

Lissack now lives in Marblehead, Mass., is executive director of a nonprofit — the Institute for the Study of Coherence and Emergence (ISCE) — that is currently focused on empowering victims of sexual assault and domestic violence. He has helped develop a mobile app that will allow victims to record, time-stamp, and store their stories on an encrypted basis until they want to go to the police or other authorities. He also sells real estate. Since his yield burning days, he formed about 10 startups (mostly software companies), eight of which failed, losing $100 million in the process.

"I had a very expensive education," he told The Bond Buyer.

He filed for bankruptcy a couple of years ago, a process that was finalized last August.

Other cases possible

The Illinois and federal False Claims Acts are similar. The Illinois law permits a private person to sue on behalf of the state against any person or company that has defrauded the state. If the suit is successful, the whistleblower is entitled to between 15% and 25% if the state intervenes and takes over the suit or between 25% and 30% if the state declines to intervene.

According to this whistleblower suit, since April 1, 2009, the eight firms served as remarketing agents for roughly 634 Illinois VRDOs valued at issuance at $18.7 billion. This represents about 65% of Illinois VRDOs outstanding during this period, the suit says. As of Nov. 30, 2013, there were about 9,000 VRDOs totaling $223 billion outstanding in the U.S., with Illinois issuing about 575 of these, it states.

The suit suggests that False Claims Act lawsuits may have been filed in several other states that are still sealed because the plaintiff’s forensic analysis appears to have covered VRDOs on a national basis and in other states as well. In addition, the suit complains about, but does not name as a defendant, Wells Fargo, a bank that serves as remarketing agent mostly outside of Illinois. That suggests there may be a sealed whistleblower suit in California.

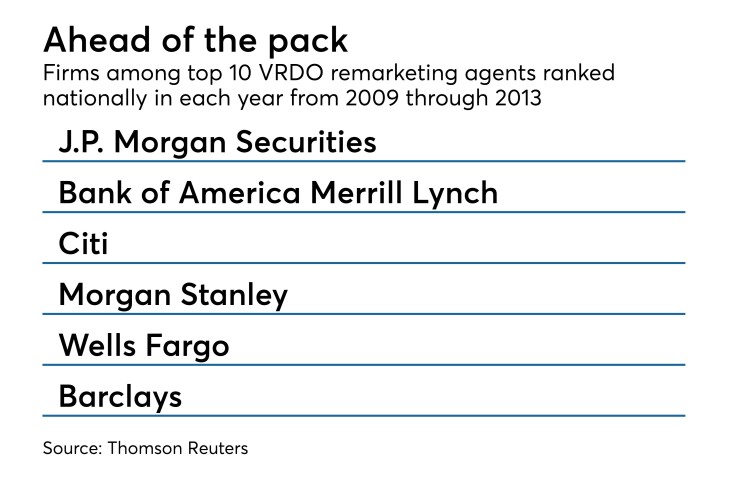

In addition, five of the firms charged in this whistleblower suit were among the top 10 nationally ranked remarketing agents in each year during the four-and-a-half-year period that the forensic analysis was conducted, according to Thomson Reuters’ data. These firms included JPMorgan, Citi, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, and Barclays. The other top-rated RMA was Wells Fargo. This raises questions of whether there may be some litigation or enforcement action underway that is national in scope.

The Securities and Exchange Commission would not comment on whether it is investigating these firms or VRDO remarketing practices.

VRDOs

VRDOs are tax-exempt, variable-rate bonds that are nominally long-term with 20- or 30-year maturities, but are considered short-term because their interest rates are reset periodically, typically weekly. They contain a “put” feature that allows investors to tender them back to tender agents or remarketing agents. The RMAs will then market the VRDOs at a par rate that is 100% of the face value of the security as well as accrued interest.

According to the MSRB, the interest rates can be determined at reset dates in one of three ways: by the remarketing agent, according to a formula, or at the highest allowable interest rate as specified in the VRDO documents. However, rate reset data published by the MSRB show the vast majority of rates are reset by remarketing agents.

For example, the MSRB’s third quarter SHORT report shows that in the third quarter of 2017, out of 102,510 VRDO rate resets, 102,319 were reset by the remarking agent, while only 128 were reset according to formulas and 63 by the maximum rate.

VRDOs are treated as short-term low risk, high liquidity, tax-free investments and are typically held by tax-exempt money market funds. They meet the SEC’s strict regulatory requirements for the types of securities that MMFs can hold.

VRDOs are usually secured by letters of credit or standby purchase agreements from high- rated commercial banks that require the banks to purchase the VRDOs if holders exercise their put rights and the VRDOs cannot be remarketed. The issuers pay fees for the LOCs, which provide credit enhancement and liquidity, and for standby purchase agreements, which just provide liquidity.

Multiple roles for firms

The firms that underwrite VRDOs typically serve as remarketing agents for the securities. It is not unusual for a bank to underwrite and remarket VRDOs as well as provide liquidity, while also owning or managing the tax-exempt money market funds that hold them, as was the case with some of these banks charged, according to the suit.

The suit claims the remarketing agents had two basic jobs under their contracts with Illinois issuers for which they were paid an average annual fee of roughly 10 basis points of the VRDO debt balance. The RMAs were required to periodically reset VRDO interest rates at the lowest possible rates, based on the characteristics of the bonds, the relevant market conditions and investor demand. The RMAs were then supposed to “remarket” the securities at the lowest possible rate when an investor exercised its put right, the suit claims.

Robo-resetting

But instead of marketing and pricing the VRDOs at the lowest possible interest rates at the reset dates as required, these eight banks and broker-dealers engaged in a “Robo-Resetting” scheme in which they mechanically set rates “en masse without any consideration of the individual characteristics of the bonds, the associated market conditions, or investor demand,” the suit charges.

Lissack believes Robo-Resetting started in the 1990s as firms’ remarketing desks shrank and they didn’t have the remarketing agents needed to reset rates of individual VRDOs.

The plaintiff’s forensic analysis showed the remarketing agents put the vast majority of the VRDOs they remarketed into “buckets” and set their interest rates collectively, according to the suit. The VRDOs in each bucket had an identical pricing spread that moved up or down in lockstep fashion, it claimed.

Lissack says the alleged fraud is evident by comparing tax-exempt VRDOs with taxable commercial paper, which are similarly periodically reset. “It’s the only part of the yield curve where tax-exempt yields are more, before adjusting for the tax exemption, than corporates and it makes no sense,” he said.

In the analysis, a bond was considered to be part of a bucket if it had identical week-over-week rate changes as other bonds in the bucket for at least 26 weeks and at least 80% of the time. “In no case are defendants making an individual determination of what the appropriate rate should be for a particular bond,” the suit claimed.

The alleged conduct of the eight remarketers violated Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board Rule G-17 that required them to deal fairly and honestly with the VRDO issuers, as well as MSRB Rule G-18 that requires them to obtain fair and reasonable interest rates for the issuers, according to the suit.

In addition, the suit charges these firms failed to follow the disclosures they are “required to set the interest rate at the rate necessary, in [their] judgment, as the lowest rate that permits the sale of the VRDOs at 100% of their principal amount (par) on the interest reset date." This is model language established by the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association in August 2012 and is typically used as boilerplate language in remarketing statements.

Alleged collusion

The suit also claims the remarketing agents colluded. “The collusion among defendants in their Robo-Resetting scheme is evident from the bucketing that has occurred across the defendant banks,” the suit charges, citing examples.

One example cites the Federal Reserve Board’s Dec. 15, 2015, decision to raise the federal funds rate by 25 basis points. Commercial paper rates responded by moving from single- digit rates to 30 to 35 basis points. But the remarketing agents “did not react at all for several months, and then in March suddenly in unison drove the interest rates on the VRDOs they managed well past commercial paper rates,” the suit alleges.

Another example cited is Moody’s Investors Services’ threatened and then actual downgrade of Bank of America’s credit rating in 2012. That had very little impact on the rates of the $35 million of VRDOs with credit support from the bank even though it lessened the attractiveness of the VRDOs to tax-exempt money market funds, the suit alleges.

“The Bank of America downgrade should have caused tax-exempt money market funds to sell many of their VRDOs backed by Bank of America,” the suit claims. “But that did not happen.”

“So this very significant event in the market ended up being a non-event in terms of VRDO rates, an outcome that can only be explained by defendants (and potentially other large RMAs) getting together and agreeing to ignore the downgrade,” the suit charges. “This coordinated response was confirmed for [Edelweiss] in an April 2012 discussion with a senior Bank of America banker who conceded the defendant RMAs had gotten together during this time and agreed it was best to keep investing in Bank of America-backed VRDOs irrespective of ratings detail.”

Edelweiss has asked the court to “enjoin … and restrain … defendants from engaging in any conduct, conspiracy, contract or agreement, and from adopting or following any practice, plan, program, scheme, artifice or device similar to, or having a purpose and effect similar to, the conduct complained of.”

It wants the court to order the defendants to pay an amount equal to three times the amount of damages Illinois has sustained as a result of their alleged violations, as well as between $10,957 to $21,916 (as adjusted for inflation) for each violation under the False Claims Act. It also wants its costs and attorneys’ fees reimbursed.

VRDO growth expected

Several market participants said last week before the lawsuit was made public that they expect the VRDO market to begin growing again after a precipitous drop and slowdown for about a decade due to the financial crisis. They also said they think it would be hard to manipulate reset rates.

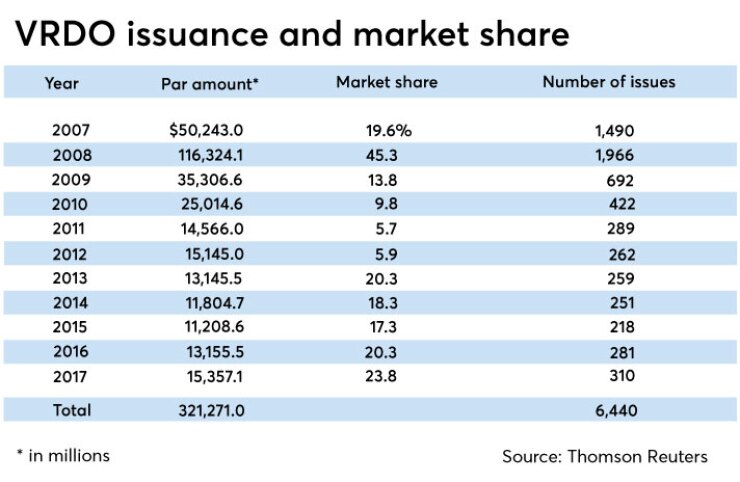

VRDO issuance started in the 1980s and peaked at $116 billion in 2008, according to Thomson Reuters’ data. But then the financial crisis hit, banks came under pressure to boost their regulatory capital and became less willing or able to issue letters of credit and standby purchase agreements. Some banks were downgraded and the VRDOs for which they provided liquidity became less attractive to money market funds.

VRDO issuance dropped fairly steadily, with a small blip up to $15 billion in 2012, to $11.2 billion in 2015. Issuance has risen since then to $15 billion last year. But market participants say they are poised to make a comeback.

“I definitely feel that the tide is flowing for VRDOs,” said Robert Novembre, chief executive officer at Clarity Bidrate Alternative Trading System, where VRDOs and other floating-rate munis are traded.

Novembre said he thinks banks’ direct purchases of munis replaced a lot of VRDOs since the financial crisis. But the huge plunge in the corporate tax rate to 21% from 35% this year has made munis less attractive to banks relative to other investments. Also, with the new tax law’s prohibition on advance refundings, variable-rate debt could prove to be a solution for issuers looking for the option to redeem at par prior to maturity, Novembre said.

Rate manipulation skepticism

Rick Kolman, head of municipals at New York-based Academy Securities, said issuers are looking for new alternatives to private placements and that VRDOs are among the options being considered. He said it isn’t clear how much money will be moving out of the direct placement market and into the VRDO market, but has heard possibilities of anything from $10 billion to $40 billion or even more.

The VRDO market is highly transparent, bankers said, because rate resets are easily seen by investors and the rates are based on the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association Municipal Swap Index. The SIFMA index is a seven-day index calculated and published by Bloomberg based on resets reported to the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board’s SHORT system and overseen by SIFMA’s Municipal Swap Index Committee. This is fundamentally different from the London Interbank Offered Rate, or Libor, which is based on bank estimates.

Ernesto Lanza, a senior counsel at Clark Hill in Washington who was deputy executive director at the MSRB when he left in 2014, said the MSRB began collecting VRDO data in 2009 because of the fallout from the Financial Crisis. Banks stopped offering the lines and letters of credit that most issuers needed for VRDOs, striking a major blow to that market.

Lanza was skeptical that a remarketing agent would have a strong incentive to set rates incorrectly. He said more sophisticated issuers would generally notice that the remarketing was not happening. But he said there is not anything really stopping an agent from at least initially setting a rate too high, either.

But pressed on the issue, Lanza said, “It is theoretically possible for a remarketing agent to not do it right.”

Yvette Shields contributed to this article.