If the Build America Bond program expires at the end of this year, long-term tax-exempt bonds could lose their latest pillar of support.

BABs represent the most recent valve the municipal market has employed to divert long-term supply from a tax-exempt market whose natural buyers are notoriously averse to long maturities.

With the possible expiration of the federal stimulus bond program looming at the end of the year, some market participants are beginning to wonder what the muni bond industry would look like without that safety valve.

The market is clearly jumpy about the prospect, as evidenced by a 45-basis-point demolition of 30-year triple-A rated paper this month, according to Municipal Market Data.

Perhaps some of this unease stems from a fear that the municipal market has gone the better part of a decade without having to find out what happens when it tries to foist too much long-term tax-exempt supply onto unwilling retail buyers.

One by one, the market has figured out methods to avoid this scenario. And one by one, those methods have evaporated.

BABs are the last one standing, and without an extension from Congress in the next month or so, they too will vanish.

Municipalities have long had trouble finding buyers for long-term tax-exempt paper.

Retail investors simply do not like owning bonds with maturities of much more than 15 years.

Wealthy investors are generally too leery of inflation to lock up money for three decades. It is also expensive for them to jump in and out of bond positions, because of trading costs.

“People just don’t want it,” said Chris Mier, managing director at Loop Capital. “The people that retail interact with — the financial advisers, etc. — encourage them to not buy long. ... From my experience, at least for the last few years, 30 years have been a tough sale for retail.”

The dearth of demand at the long end conflicts with a need for municipalities to issue long-term debt, since they are often financing long-term projects.

The past decade of municipal finance has largely been a tale of state and local governments figuring out ways around this gap in demand, either by structuring securities that behave like short-term debt or finding other types of buyers to gobble up long-term tax-free bonds.

From variable-rate demand obligations to auction-rate securities to tender-option bond arbitrage to Build America Bonds, many of the most innovative financing tools — and biggest risks — the municipal market has undertaken in recent history were simply ways to avoid stuffing long-term tax-exempt paper into the hands of retail investors who didn’t really want it.

TOBs, VRDOs, and ARS disintegrated with varying degrees of spectacularity during the onset of the credit crisis. BABs, established as a way to expand the market for municipal debt in answer to the crisis, are on the verge of vanishing too, although sources in Washington now say a one-year extension appears likely, with a lower interest subsidy from the U.S. Treasury.

Without these props, market participants say, municipalities will be forced to concede higher interest rates on long-term debt to placate duration-averse investors, just like in the old days.

Historically Speaking

Time was, long-term tax-exempt yields were much higher than short-term yields.

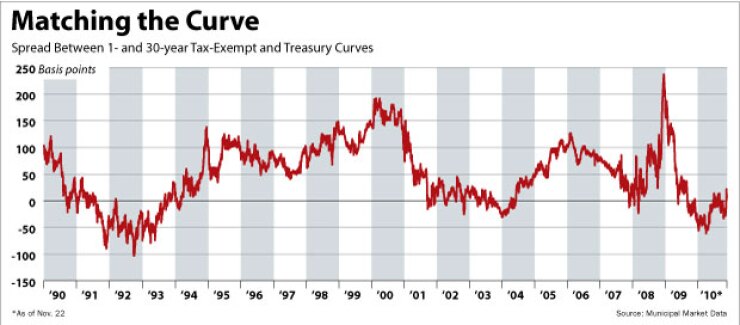

As the graph on this page shows, the tax-exempt yield curve for most of its history has been steeper than the Treasury curve, often significantly so.

Without a strong buyer base for long-term tax-exempts, municipalities had to pay higher interest rates to finance long-term projects.

The tax-exempt curve was about 100 basis points steeper than the Treasury curve for most of the 1990s.

Last decade, the curves converged.

This was no coincidence.

A group of hedge funds and other investors noticed how steep the tax-exempt curve was, and they sought to exploit the market inefficiency.

These funds played one curve against the other, and heaped on leverage using a structure known as tender-option bond arbitrage.

The TOB trade entailed borrowing at a short-term muni rate and using the proceeds to buy long-term tax-free bonds, hedging both with opposite positions on taxable rates such as the London Interbank Offered Rate.

The idea was to capture the additional basis points offered by the municipal yield curve compared with the taxable curves.

Regardless of the merits of the TOB funds’ investment thesis, the upshot was they bought a lot of long-term tax-exempt bonds.

No formal tally of how big these funds were exists, but Municipal Market Advisors’ Matt Fabian reckons at their peak they had grown to anywhere from $300 billion to $500 billion, soaking up as much as a quarter of annual municipal bond issuance some years.

“They were enormous,” Fabian said. “It was a way for the dealer community, and the hedge fund community, to create demand when they needed it to help issuers get into the market at lower rates.”

The emergence of demand from hedge funds was not the only thing compressing long-term rates during that era.

Municipalities also began selling auction-rate securities, which is nominally long-term paper with an interest rate that resets regularly at an auction.

The auctions transformed putatively long-term debt into effectively short-term debt, enabling municipalities to borrow from retail investors and other participants more comfortable holding municipal paper for two weeks than 30 years.

By some estimates, the municipal ARS market swelled to $200 billion in its heyday. This was all long-term borrowing that was wheeled from the long end of the yield curve into a short-term market.

When bidders abruptly disappeared from the auctions in February 2008, many municipalities refunded their ARS and replaced them with VRDOs.

Like ARS, variable-rate demand obligations are nominally long-term instruments with interest rates that reset regularly. The difference is VRDOs typically require the municipality, or a bank paid by the municipality, to buy the debt back from the holder if nobody else wants it.

The advantage to this put feature is the VRDO then becomes eligible to be purchased by money market funds — the ultimate short-term buyer.

VRDOs outstanding by 2009 totaled nearly $450 billion, according to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association.

While many VRDOs simply replaced ARS, they enabled the market to persist in dressing up its long-term debt in short-term clothing.

Between the TOBs, the VRDOs and the ARS, hundreds of billions of dollars of what could ordinarily have been long-term tax-exempt paper fobbed onto reluctant retail investors demanding higher yields was instead either absorbed by leveraged hedge funds or morphed into what effectively was a short-term product.

From 2002 to 2007, 29% of all municipal borrowing was either VRDOs or ARS, according to Thomson Reuters. Without these products, much of the supply likely would have been headed for the long-term tax-exempt sector, where it would have pushed up rates and steepened the yield curve.

The TOB programs, coupled with the transference of long-term issuance into short-term markets, helped buttress long-term tax-free yields by paring down supply.

That introduced what at the time was a new normal for the tax-free market: a yield curve that was just about as flat as the Treasury curve, most of the time.

New Normal Unraveled

The leverage the TOB funds layered on turned out to be their undoing, and many were forced to liquidate in 2007 when the correlations between the positions and the hedges went awry.

The ARS market collapsed when bidders stopped showing up. While VRDOs haven’t exactly collapsed, they are becoming less viable as financing structures for municipalities because bank guarantees have become scarce and expensive.

Municipalities also began to rely on bond insurance to make their debt more palatable to retail investors. The credit crisis demolished insurers’ ratings, and now well less than 10% of muni bonds are coming to market insured.

With TOBs inactive, insurance diminished, the ARS market dead, and the VRDO market shrinking, coming out of the financial crisis the tax-exempt sector was beginning to face the reality of the steeper tax-exempt curve it had known prior to the credit bubble.

In February 2009, President Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act into law.

The BABs feature in that law has had a powerful effect on long-term municipal borrowing costs.

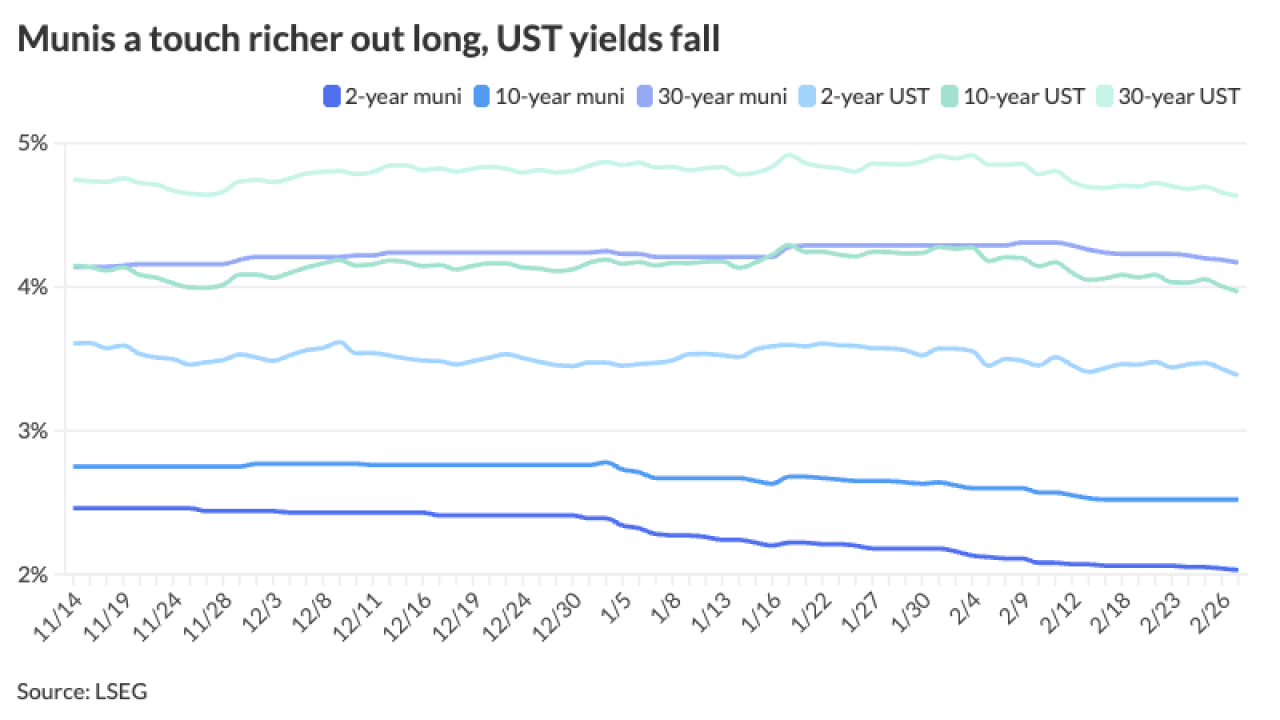

For most of 2010, the tax-exempt curve has actually been flatter than the Treasury curve.

In a report last week, Citigroup municipal strategist George Friedlander estimated municipalities that use BABs for long-term financing save a full percentage point versus what they would incur in a tax-exempt-only market.

Even municipalities that don’t use BABs still save around 50 basis points because of the program, Friedlander surmises, because it removes so much supply from the long end.

In other words, BABs have been doing what TOBs, ARS, and VRDOs were doing last decade until they fell apart: flattening the tax-exempt yield curve.

Slightly more than a quarter of municipal borrowing this year has been BABs, siphoning substantial supply out of the long-term tax-exempt space.

“BABs are the latest mechanism that can efficiently and materially mitigate the structural inefficiencies in the long end of the tax-exempt curve,” JPMorgan analysts Chris Holmes and Alex Roever wrote last week in their outlook for 2011.

There was a period in 2008 and early 2009 when no such mechanism was pulling down long-term tax-exempt rates. While needless to say, there was a lot going on during that time, the tax-exempt yield curve was an average of 70 basis points steeper than the Treasury curve in 2008, and 140 basis points steeper in the first three months of 2009.

It was at least in part the BAB program that flattened it again.

Municipal market volatility spiked earlier this month, with 30-year triple-A yields vaulting nearly 50 basis points in two weeks.

A Wild Ride

Yields leaped 20 basis points on Nov. 17 alone, according to MMD — this for a market where a lurch of five basis points in either direction is significant.

Pundits and analysts blamed a supply deluge for the sharp increase in rates. Municipalities were storming to market with huge batches of debt coincident with a massive withdrawal of cash from tax-free mutual funds, and the Street just didn’t have the capacity to absorb it all.

But are municipalities really bringing that much supply to market?

From Nov. 8 to Nov. 19 — a time during which long-term yields spiked 47 basis points — municipalities sold $25.8 billion of bonds, according to Bloomberg LP.

This was indeed the heaviest two-week slate since 2006.

But only $12.8 billion of this was tax-exempt — still high for a two-week stretch, but hardly shape-shifting.

Of the roughly 410 two-week periods since the beginning of 2003, 117 of them have brought more than $12.8 billion of tax-exempt supply, according to Bloomberg.

Supply explains even less of the sell-off of long-term tax-exempt bonds when one considers the maturity breakdown of the offerings.

Of the tax-exempt bonds dated in this two-week period, $5.87 billion matures in 15 years or more. In the comparable period in 2005, municipalities sold an almost-identical amount of debt overall — and $7.8 billion of tax-exempt debt with maturities 15 years or more.

In the corresponding period in 2006, they sold $10.5 billion of tax-exempt debt that was 15 years or longer.

And in both these periods in 2005 and 2006, long-term yields actually fell.

Michael Zezas, municipal strategist at Morgan Stanley, said the outburst in supply this month has forced people to confront the market’s capability to absorb long-term tax-free paper in the potential absence of BABs.

“The increase in supply reminded people that there aren’t a lot of natural buyers of long-term muni bonds,” he said. “It reminded them that demand would not match increasing supply if BABs are not extended.”

The collapse of Demand

This month, heavy supply was met with a severe drop in demand.

Tax-free mutual funds reported $4.8 billion in redemptions during the week ended Nov. 17, according to the Investment Company Institute. Withdrawals from long-term funds dominated, according to data from Lipper FMI.

The long-term tax-exempt sector, aside from being buttressed by BABs, has enjoyed uncommon support from mutual fund buying since early 2009.

In September, long-term tax-free funds were getting more money each week than they had almost any time in 20 years, Lipper data shows.

The truth is that for most of its history, the long-term tax-exempt sector has suffered from more supply and less demand than it has gotten in 2009 and 2010.

MMA’s Fabian said the tax-free sector has in fact been substantially weaker for months.

In late summer, dealers did not want to touch long-term bonds, he said — the sector was so illiquid and thin that there were not enough trades to demonstrate how weak the market was.

The MMA scales tried to price this malaise in before the selling actually took place, which is why the MMA scales show a less drastic sell-off than the MMD scales.

Market participants say there is no reason to panic — just brace for higher long-term tax-free rates and a steeper yield curve.

“In general the assumption is for a steeper curve,” Fabian said.

“It’s an environment where, broadly speaking, the curve is steeper than flatter,” according to Loop Capital’s Mier.

Nobody is predicting it will be impossible for municipalities to sell 30-year tax-free bonds. They’ll just have to offer more yield to tempt buyers.

Morgan Stanley’s Zezas pointed out that after the recent spike in yields, investors did step in and begin to pull yields down somewhat.

“It’s encouraging in the sense that the market was able to find levels at which the retail buyer would support that part of the curve,” Zezas said. “But obviously that would reflect a new normal in the tax-exempt market, as opposed to what the market experienced before 2008.”

Holmes and Roever expect long-term spreads to widen 12 to 25 basis points if the BAB program is allowed to expire. They also believe municipalities will not issue as much debt, since the market would not support it.