Any reforms made to the tax-exemption of municipal bonds should be "careful and deliberative, particularly in how they treat previously-issued debt," a report from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget warned.

But the group also noted that tax reform could allow the federal government to make subsidies to public investments more efficient and to make gradual changes to subsidies that are undesirable. Tax reform also could generate revenue that could be used to reduce tax rates and the deficit, it said.

"The exclusion for interest on state and local bonds is an expensive tax preference that steers investors toward a category of investments that may not otherwise be preferable to unsubsidized investments," said CRFB, a bipartisan nonprofit that educates the public about fiscal issues. "On the other hand, states and investors have come to rely on tax-free municipal bonds as the main way to finance infrastructure. Importantly, whatever the merits of having the exclusion in the first place, there is a $3.7 trillion market built around the exclusion."

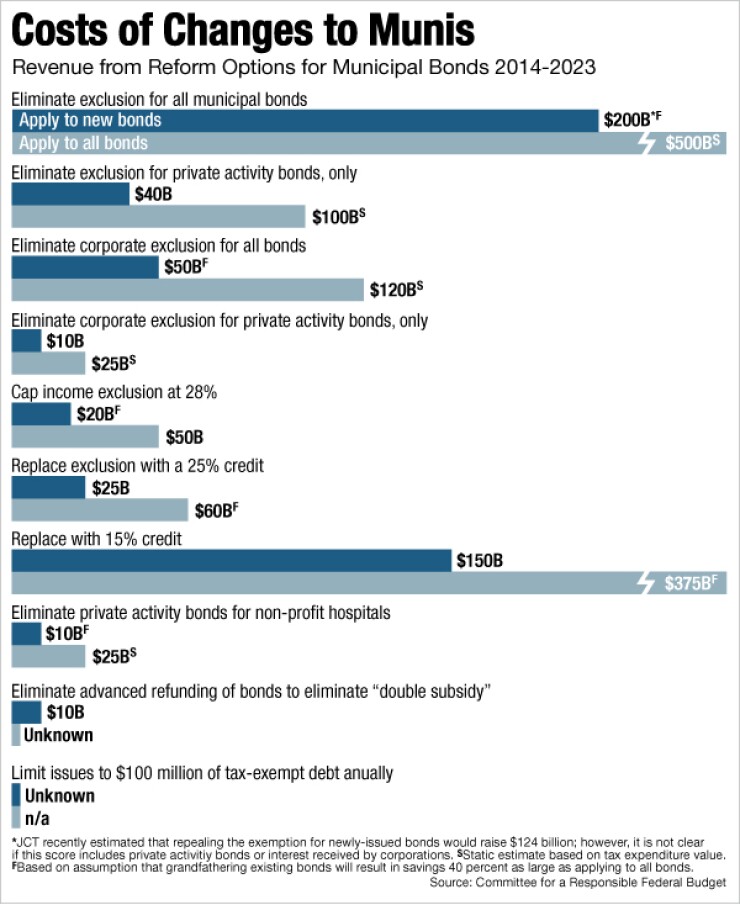

The CRFB's report, part of a series that analyzes and reviews the tax breaks under discussion as part of tax reform, includes a chart with estimates about how much revenue would be generated over 10 years if various reforms were made to the municipal bond tax-exemption.

The data is based in part on estimates from the Joint Committee on Taxation and from private and public groups. It is also based on the CRFB estimates that assume that grandfathering existing bonds will result in 40% as much revenue as applying a reform to all bonds, said CRFB senior policy director Marc Goldwein.

The report said that eliminating the exemption for all new municipal bonds would raise $200 billion in revenue from fiscal 2014 to 2023, while eliminating the exclusion for all munis would raise $500 billion during that period.

It also said that capping the value of the exemption at 28%, as President Obama proposed in his fiscal 2014 budget, would result in $20 billion in revenue in the next 10 fiscal years if applied to new bonds and $50 billion if applied to all bonds.

Replacing the tax-exemption with a 25% tax credit, like the 2011 proposal by Sens. Ron Wyden, D-Ore. and Dan Coats, R-Ind., would raise $25 billion in the next 10 fiscal years if required for new bonds and $60 billion in the same time period if required for all bonds.

The tax-exemption on interest income will cost the federal government $58 billion in fiscal 2013 and about $540 billion over the next 10 years, according to JCT numbers cited in the CRFB report.

Tax exemption is the third largest portion of federal aid to states behind federal grants and the state and local tax deduction, the report said.

Supporters of tax-exemption argue that it helps state and local governments make public investments, including those in infrastructure, education and health care. They also warn that making changes to the exemption could result in large disruptions in the muni market and the broader economy and could hurt state and local governments' abilities to borrow money, the report said.

But those who oppose excluding municipal bond interest from income tax believe that the tax code shouldn't be used to support local governments and local projects - particularly those like sports stadiums that have a private purpose and benefit a small number of people, CRFB said.

Opponents of tax exemption also argue that the policy is an expensive and poorly-targeted way to encourage investment in important projects, the report said. They note that the exclusion gives people who want to reduce or eliminate their tax burdens a large benefit, with the tax-exemption being the reason why many wealthy people do not pay any taxes.

Mike Nicholas, president and chief executive officer of the Bond Dealers of America, said the revenue numbers for capping or eliminating the tax exemption mentioned in the report are "greatly exaggerated." He said that investors are dynamic and won't automatically default to investing in taxable bonds if the tax exemption for munis is eliminated.

"They don't make investment decisions in a static environment," Nicholas said.

Additionally, Nicholas said that issuance would be affected by changes to the tax-exemption. When munis are less attractive in the secondary market, borrowing costs will increase and taxes will increase to pay for the rising borrowing costs. Rising borrowing costs will also hurt investment in infrastructure.

"On a net basis, the negative consequences are much higher or worse than the positives of taxing municipal debt," he said.

Nicholas also noted that municipal bonds are not just held by the wealthy, and that the majority of investors in tax-exempt debt have household incomes below $250,000.