CHICAGO—Illinois faces a sea of red ink because shrinking income tax revenue will fail to keep pace with rising pension and health insurance costs, according to outgoing Gov. Pat Quinn's latest three-year

The Dec. 31 report offers a dim view of the state's fiscal prospects, despite years of chipping away at a backlog of unpaid bills, and illustrates the stark impact of the Jan. 1 rollback of individual and corporate income tax rates after temporary 2011 increases rolled off on schedule.

The projections from the Office of Management and Budget warn that the estimated $4.1 billion bill backlog expected at the close of fiscal 2015 could grow to $9.9 billion in fiscal 2016, $15.7 billion in fiscal 2017, and reach $21.3 billion at the close of fiscal 2018.

The state has offered a three-year forecast since 2011.

At the same time, a general funds deficit of $180 million this year will rise to more than $5 billion in the coming years.

The Civic Federation of Chicago in a review of the figures said they "were not surprising" and show "the consequences of the income tax decline."

Quinn, as he unsuccessfully pressed lawmakers last year to make permanent the 2011 tax hike, warned lawmakers that years of progress would be reversed if they expired.

Facing an election, lawmakers balked and adopted a fiscal 2015 budget that is now $750 million short of the actual funding needed to support costs.

The expectation, at the time, was that lawmakers would return early this year to extend the expiring rates.

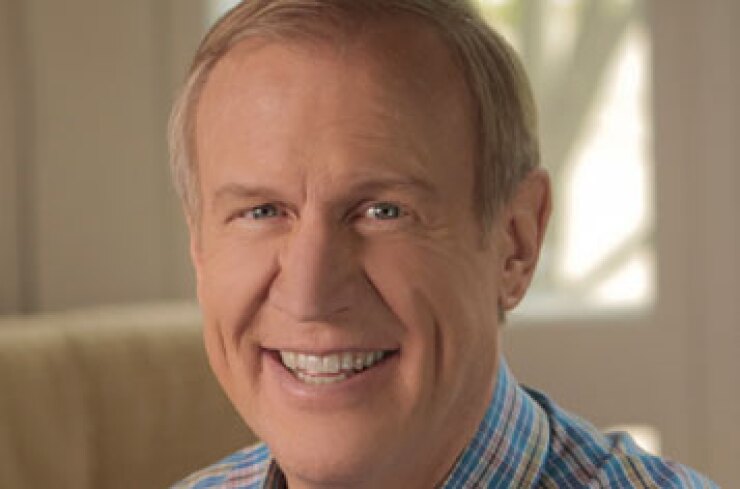

The task of balancing the current budget that runs through June 30 and dealing with skyrocketing red ink falls to Gov.-elect Bruce Rauner, who has warned that state finances are in even more dire shape than he thought. He has, at least temporarily, backed away from his campaign pledge not to extend the higher rates.

Rauner, who defeated Quinn in November, takes office Monday and his budget is due Feb. 18 unless he asks for a delay. The Republican faces veto-proof Democratic majorities in the General Assembly.

Illinois' reputation, credit rating, and borrowing costs are at stake. It's already the lowest rated state at the A-minus level with negative outlooks from Fitch Ratings, Moody's Investors Service, and Standard & Poor's.

Many investors are skeptical of the state's ability to manage its budget without the expired higher tax rates

Investors want to see structural change, from both cuts and an extension of the higher tax rates, said Alan Schankel, a managing director on Janney Capital Market's fixed income strategy team. While Rauner campaigned against the higher tax rates, he's left himself "some room to maneuver" politically by not ruling an extension out and stressing the state's dire condition while also not committing to any one fix, Schankel said.

"I think investors are looking for some hard decisions to be made," he said. "He's not going to solve the state's problems overnight, but investors want to see some structural progress."

The bond market demands steep penalties for the state to borrow, penalties that trickle down to most Illinois-based borrowers, especially those that rely on state aid or tax payments that are often delayed when the state extends its bill payment cycle to preserve its liquidity.

Spreads on Illinois' 10-year GO paper to the Municipal Market Data top rated benchmark have narrowed since they hovered in the 170 basis point range over the summer. They have recently fallen from 150 basis points last month to a 140 basis point spread in recent days. Schankel attributed the change to a general risk spread narrowing rather than any specific Illinois-related factor.

A Dec. 15

The $21 billion out-year projection for unpaid bills is more than double the more than $9 billion high hit a few years ago.

The OMB's Dec. 31 projections call for individual income tax revenues to drop by $1.8 billion this year to $14.8 billion from $16.6 billion, with corporate tax collections falling to $2.7 billion from $3.2 billion. Individual income tax collections then drop again in fiscal 2016 to $12.3 billion as the state sees a full fiscal year at the lower rates, before climbing due to natural growth to $12.8 billion and then $13.2 billion in fiscal 2018.

Debt service holds steady over the three years at between $2.2 billion and $2.3 billion as do general agency costs, while pension and healthcare costs will rise.

The figures don't incorporate any savings from 2013 pension reforms that are under a legal challenge that will be decided by the Illinois Supreme Court. The high court will hear arguments in March.

The state's

Group health insurance will increase by $285 million to $1.9 billion in fiscal 2016 from $1.6 billion this year in part due the state's reimbursement of $140 million to retirees following an Illinois Supreme Court decision last year ruling that healthcare subsidies are protected under the state constitution, according to a review of the numbers posted by the Civic Federation of Chicago's Institute for Illinois' Fiscal Sustainability.

The state projections reflect no change in the income tax rates, which dropped Jan. 1 to 3.75% for individual payers from 5%. Before the 2011 hike, the rate was 3%. The corporate rate fell to 5% from 7%. The corporate rate was at 4.8% before the hike. The state operates on a roughly $35 billion to $36 billion operating budget.

Sales taxes are projected to rise at a modest clip to nearly $8 billion this year from $7.7 billion last year hitting $8.8 billion in fiscal 2018.

The Center on Tax and Budget Accountability issued its own report with similar dire warnings that the state faces a $12.7 billion accumulated deficit by the end of fiscal 2016 when its overdue bills carried into the next fiscal year are counted.

"The state's long-term fiscal shortcomings will be on full display in the coming legislative session," said Ralph Martire, executive director of the center. "As it stands now, Illinois' current fiscal policy is unsustainable."

Rauner's lead budget advisor on the transition team, Tim Nuding, in a report last week laid the blame for the state's budget mess on "years of budget mismanagement and dishonesty."

Rauner has not yet offered specific plans for shoring up the state's balance sheet.

The transition team's report attacked $2.2 billion of what it labeled "budget gimmicks" and accused the state of breaking the law requiring balanced budgets.

"Our challenges are not simply a revenue problem. We have a structural problem decades in the making," wrote Nuding, who serves as chief of staff to state Senate Minority Leader Christine Radogno and the Senate Republican caucus. "Illinois government must undergo major structural reforms and implement honest budget practices that together address the long-term challenges of the state."

The report noted the state's credit deterioration, driven by its structural budget woes and $111 billion of unfunded pension obligations in a system that is just 39% funded.

Rauner has so far offered only general ideas for balancing the state's books. A 10-point fiscal blueprint released during the campaign called for trimming $1 billion in spending, cutting state purchasing and cracking down on Medicaid eligibility, among other ideas.

Rauner said he would eliminate state shuttles for lawmakers and the governor and sell the existing state planes, cut lawmakers and state constitutional officers' pay. He wants to overhaul the state's tax system and expand the sales tax to cover some services.

Fitch Ratings wrote in a recent report that near-term management decisions in Illinois, as well as California and New Jersey, would prove critical to credit quality in those states.

"Taking steps to address the longstanding structural mismatch between revenues and spending would put the state on more solid financial footing, while failure to take action would be a return to past practices and leave the state particularly poorly positioned to confront future downturns," analyst Laura Porter wrote of Illinois.