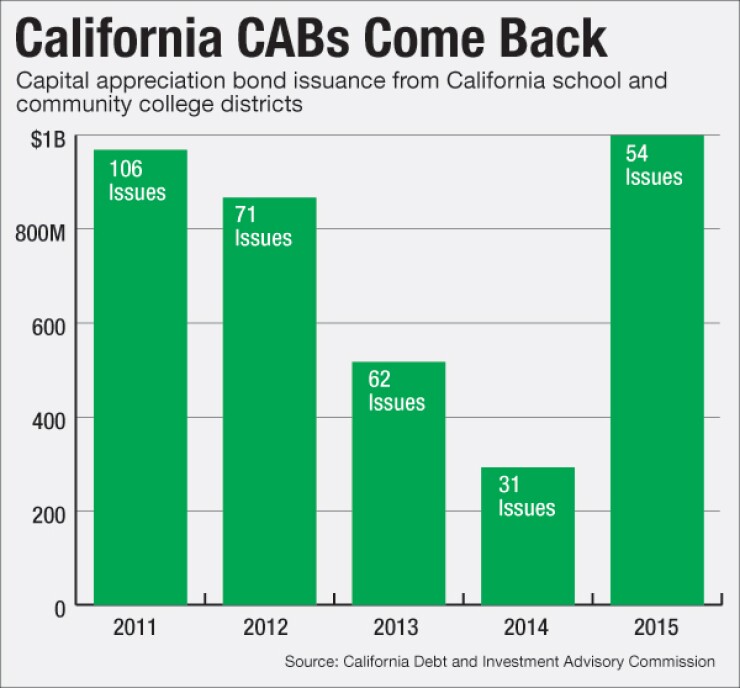

LOS ANGELES -- Issuance of capital appreciation bonds by California school and community college districts more than tripled from 2014 to 2015 despite a law designed to limit their use of the bond structure.

School and community college districts only issued $292 million of CABs in 2014, the year the law took effect, but issuance spiked in 2015 to $999 million, according to data produced by the California Debt and Investment Advisory Commission at The Bond Buyer's request.

It was the highest level of school CAB issuance since 2009, according to CDIAC data.

State lawmakers passed Assembly Bill 182 at the urging of then-State Treasurer Bill Lockyer after it came to light that many school districts had issued non-callable capital appreciation bonds with 40-year maturities and nominal interest-to-principal repayment ratios of 10-to-1 or even 20-to-1.

The CAB deal most often cited in calls for reform was Poway Unified School District's $105 million series, issued without a call option and requiring $1 billion of debt service through its 40-year maturity.

Deputy State Treasurer Tim Schaefer said CDIAC will have to drill down into the data more to come up with an explanation as to why issuance grew so much in 2015. CDIAC, a clearinghouse for public debt issuance information in the state, falls under the auspices of State Treasurer John Chiang's office.

"At first glance, this shouldn't be happening, but it is happening, so we need to understand why," Schaefer said. "We have to get to the bottom of it – and CDIAC is set up to research it."

The legislation imposed limits on CAB issuance by K-12 and community college districts, requiring ratios of total debt service to principal for each series not exceed 4-to-1, and that bond issues include a 10-year call option. Permitted maximum interest rates were cut to 8% from 12%.

Schaefer said that by mid-February he hopes to have an explanation about why issuance has grown so substantially.

Schaefer said research could indicate a need to ask the Legislature to tweak the law.

"What I want to learn is: Is there an issue or issues, or an issuer or issuers, who are driving what appears to be anomalous data?" Schaefer said. "It's not logical on the face of it."

K-12 school districts conducted 46 CAB sales in 2015 totaling $691 million, compared to $250 million the prior year. The state's community colleges executed eight CAB sales last year totaling $307 million, up from $42 million in 2014.

Schaefer said he did not want to speculate on the numbers without taking a deeper look at the individual issues to see what may have driven the increase.

"There is not anything intrinsically wrong with CABs; it's how a CAB is used – and whether we educate our public servants and officials about the risk and rewards of using a CAB approach," Schaefer said.

Using a CAB requires more than a rudimentary understanding of some fairly sophisticated finance, which is not beyond the understanding of well-educated, dedicated local public servants, but they don't come to this understanding intuitively, Schaefer said.

"That is why it's important for everyone to slow down, identify the nomenclature on things and identify the risks," Schaefer said. "If you are a local school district issuer, and you have done all those things, I'm not going to presume to know what the best public policy is for your district."

The issuance jump in 2015 appears to contradict comments from some financial advisors and district officials, who have said that districts have been steering away from the structure after the wave of criticism that resulted in AB 182's passage in 2013.

"I think issuers and their communities are much more sensitive to the type of debt they are issuing and ask more questions," said Adam Bauer, president and chief executive officer of Fieldman Rolapp & Associates, a financial advisory firm. "I think this has gone to the point of no CABs."

Bauer said the negative perception, even more so than the legislation, has resulted in the districts he represents not issuing CABs even when they can.

The public and media attention that grew out of the Poway Unified deal, and Lockyer's public support for the bill to rein in CABs, gave the bond structure such a bad reputation that many district officials vowed to preclude issuing the bonds as an option, even though AB 182 set limits on the structure.

Some school districts are trying to get out of what they now see as burdensome structures. Financial advisor Dale Scott has been working with them on a program he created to shift debt from CABs into current interest bonds.

He uses a tender offer to buy back non-callable CABs to alleviate concerns that building projects that benefit the current generation would be paid for in a balloon payment by a future generation.

His restructuring program typically follows the CAB buyback by issuing current interest bonds at shorter maturities and with annual principal and interest payments standard for CIBs.

"In each of the districts, with a couple of exceptions, we were dealing with non-callable CABs with a repayment ratio greater than four-to-one and in some cases much greater," Scott said. "We were able to restructure those CABs by acquiring them directly and restructuring them into callable CIBs."

CABs pay a compounded interest rate and principal upon maturity, rather than annual principal and interest payments common to current interest bonds.

Scott said he has worked on refinancings for nine school districts that will result in a total of $250 million in cash flow savings, or what he calls taxpayer savings, by reducing total principal and interest paid.

In order to shift part of the debt to annual payments and shorter maturities, many school districts have to raise tax rates.

He said the increase has ranged from zero to $10 per $100,000 assessed value.

Napa Unified School District closed on its refinancing on January 21. It refunded $118 million of non-callable CABs into current interest bonds, producing $45.6 million of cash flow savings and $9.45 million of net present value savings.

Wade Roach, Napa USD's assistant superintendent of business services administration, said they decided to work with Scott because of criticism from a local taxpayer's association of CABs the district issued in 2009 and 2010, in conjunction with the Build America Bond program that provided federal subsidies for taxable interest.

The interest-to-principal payback ratio on Napa USD's CABs was 6.3-to-1 with total district debt at a 3.26-to-1 ratio, Roach said. It amounted to paying back $29 million in debt at a cost of $154 million, he said.

The district's general fund budget is $180 million.

After the transaction, the district's remaining CABs have a 4.3-to-1 interest to principal ratio. The district's total ratio went to 1.94.

Regular CIBs are 1.7. The new debt that replaced the CABs has a 1.55 ratio.

The average property tax increase is $13.88 per $100,000 of assessed valuation, Roach said.

"The taxpayer's association has been in favor of this since we started talking about it," Roach said. "We didn't think it was possible and they are happy we were able to complete this transaction."

For his district, Roach said CABs are off the table.

"The board has a bad taste in its mouth for CABs," Roach said. "I don't see us issuing CABs in the foreseeable future, though per se there is nothing wrong with CABs. I just think it is better if CABs are callable."