Editor's Note: The Pension Crisis — Part 1 of 4

Part 2:

Part 3:

Part 4:

This is the first part in a four-part series on pension funding, among the thorniest issues for many U.S. states and municipalities. The average median funded ratio of major pension funds has hovered around 70% since the recession, down from 85% in 2007, as governments have struggled to put pension funding back on firm ground.

This article details the demographic shifts that now threaten to worsen the crisis as America ages. Subsequent installments focus on how municipalities have fared in court when they tried to cut pension benefits; political gridlock over pension reform; and bondholders' futility as they've squared off against pension funds in bankruptcy court.

U.S. municipal pensions, weakened by decades of underfunding, now face a demographic double-whammy: People are living longer and baby boomers are reaching retirement age.

These two trends will heighten pressure on states and municipalities to increase revenues or reduce benefits to restore pension funding to sustainable levels.

"The public sector workforce is relatively flat, while the number of retirees continues to rise, affected both by the rising retirements … and the longer lifespans that retirees are benefiting from." Fitch Ratings senior director Doug Offerman wrote in an email. As a result pension liabilities are turning out higher than projected, he said.

The cost of longer lifespans should have been anticipated and calculated into plans but has not, making stated actuarial net pension funded ratios overly optimistic.

Pension plan administrators have known for decade that the retirement boom was coming. However, only now are the plans and their parent governments starting to have to pay the costs.

According to the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services the average life expectancy of a white male born in 1900 was 48.2 years. By comparison, the average life expectancy of a white male born in 2011 was 76.3 years.

A greater and greater portion of the U.S. population is living beyond age 65 and those that do are living more years. With the ratio of retired to active workers generally increasing, governments are increasingly called on to increase their own contributions to relieve the financial stress on their active workers.

When accountants prepare government financial statements, the adequacy of pension funding is partly based on life expectancy. The question is what expectancy to use. By 2013 most states and large municipalities were using a modified version of U.S. life expectancy tables provided by the Society of Actuaries. The SOA table has since been updated to 2014. To account for the fact that longevity was expected to continue to rise and that most retirees were expected to die in the future and not the present, the 2014 data was actually an estimate for how long people would live in 2021. As an estimate of an average lifespan for a given year the estimate is called a spot estimate.

However, most 65 year olds who retired in 2014 will live beyond 2021 and since it is likely that lifespans will be even longer in the years following 2021 than in that year, some actuaries use a different method of estimating lifespans. The generational method "fully incorporat[es] anticipated future improvements in longevity," according to Alicia Munnell, Jean-Pierre Aubry and Mark Cafarelli, authors of the paper, "How Will Longer Lifespans Affect State and Local Pension Funding?"

Using this method one gets longer projected lifespans than in the 2021 spot method. The longer lifespans increase liabilities.

In 2009 the Society of Actuaries looked at the experience of private pensions and came up with a revised estimate of lifespans, different from the one used by municipal governments from 2009 and beyond. "Liabilities would increase by 1.75 percent if plans adopted [this new estimate], which would reduce the 2013 funded status of state and local [pension] plans from 73% to 72%," Munnell and her associates reported in their paper, published in 2015 the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College web site.

However, "If plans were required to adopt a generational, rather than a static, version of [the new estimate], their assumptions would fall short by 2.3 years, implying an 8% increase in liabilities and a funded ratio of 67%."

Munnell and her co-authors caution that public sector retirees may prove not to have the same lifespans as those in the private sector. They say their work doesn't reveal a "serious problem" for government pension plans.

On a more cautionary note, in a survey of 150 public pensions they wrote that a switch to using generational estimates would have led to the biggest drops in actuarial required funding ratios in those plans that are already at the lowest funding levels.

Government Accounting Standards Board statements 67 and 68 required government pension plans and governments themselves to follow actuarial standards of practice set by the Actuarial Standards Board. They were also required to disclose their actuarial assumptions in their financial statements. These statements went into effect on June 30, 2014, and June 30, 2015, respectively.

The board allows pension actuaries to pick the mortality table to use, and many use the Society of Actuaries tables. The reported ratio of funding of pension plans in financial statements is partly determined by which table is chosen.

Researchers have found that government retirees have been living longer than expected, said S&P Global Ratings senior director John Sugden. This is one of the reasons that state pension systems have been experiencing higher-than-expected payouts.

A second major demographic shift affecting public pensions is the retirement of the Baby Boom generation.

In the Depression and during World War II, many U.S. adults avoided having children. When men came home from the front after World War II the economy was strong and many couples chose to have babies. This led to the Baby Boom which lasted from the end of World War II in August 1945 to about 1964.

This generation is now retiring. "In 2003, 82% of boomers were part of the labor force; a decade later, that number had declined to 66%, and it will only continue to fall," wrote Ben Casselman in 2014 in "What Baby Boomers' Retirement Means for the U.S. Economy," for fivethirtyeighty.com.

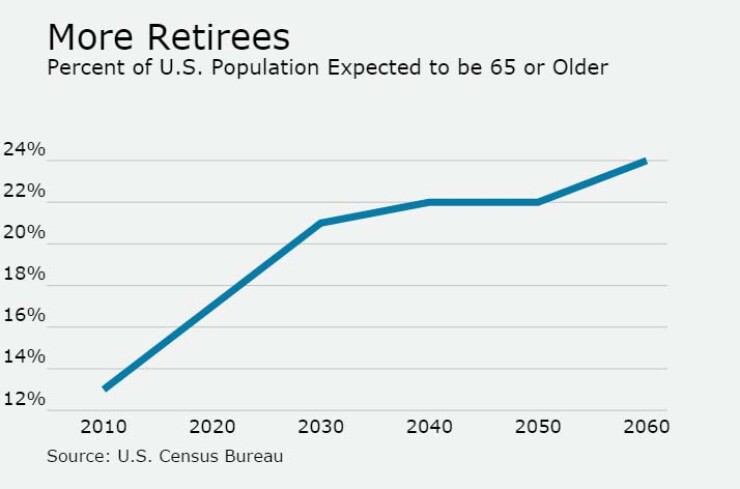

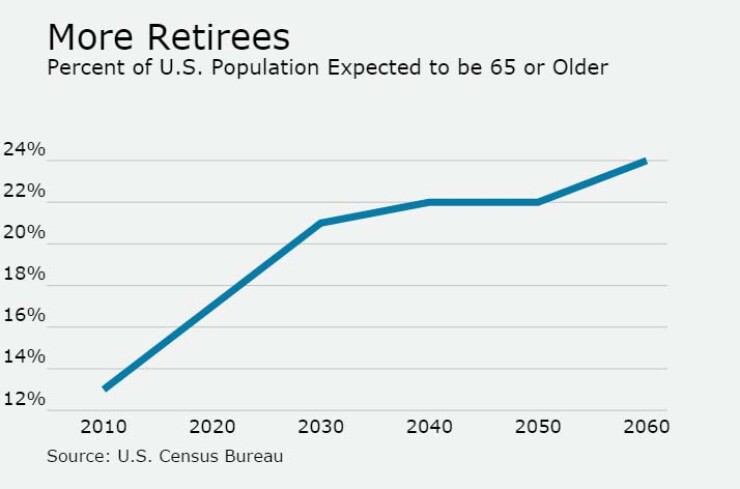

In 2014 62% of the U.S. population was from 18 to 64 years old and 15% was 65 or older, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In 2060 there will be 57% in the middle aged group and 24% in the elderly group.

While pension plans have attempted to fund their pension plans to anticipate this wave of retirements, now the plans actually have to pay for the pensions. Furthermore, most governments pay their retiree other-post-employment-benefits on a pay-as-you-go basis. Now that the number of retirees is swelling so are these benefits. The increasing portion of the population that is elderly also tends to push up state government costs for Medicaid, Sugden said.

"Retiring baby boomers are a factor in rising fiscal pressure from state and local defined benefit pensions," Fitch's Offerman wrote. "Pension contributions are a source of fiscal pressure for governments, but this is generally a bigger factor at the local level than at the state level. Pension contributions make up a larger share of local budgets than state budgets."

Most governments have managed to deal with the increased pension funding pressure, Offerman said. However, a small number have been struggling with them. Government reforms of pension benefits and contributions generally only help to reduce pension funding pressures over the long term.

Sugden pointed to another way the greying population has had a negative fiscal impact. S&P economists say that this development cost the United States 0.6% per year in economic growth in 2004 to 2014 compared with the previous 10 years. They believe it will shave a further 0.8% per year in the next eight years compared to 2004 to 2014. This slowdown has already impacted government revenues and will continue to do so.