U.S. banking regulators this month published two rules that may damp investment by banks in municipal bonds.

The more significant change will require the largest banks to account for any credit or interest-rate-related price drops in their investments, including municipals, in their available-for-sale portfolios, thus reducing capital available to back further investments. Smaller banks or savings and loans can opt out of the rule.

Under the other rule, adopted over objections from the muni industry, revenue bonds will maintain a 50% risk weighting, making it more expensive for banks to hold them than general obligation bonds, which retain a 20% risk weighting.

The changes stem from the combined efforts of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency within the Department of the Treasury, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to revise risk-based and leverage capital requirements for banks as required by the Third Basel Accord. The final rule, published in two stages on July 2 and one week later, consolidates three separate notices of proposed rulemaking that the OCC, the Fed, and the FDIC published last year.

The regulating government agencies’ set a mandatory compliance date of Jan. 1, 2014, for the largest banking organizations that are not savings and loan holding companies. All other covered banking organizations must be in compliance one year later.

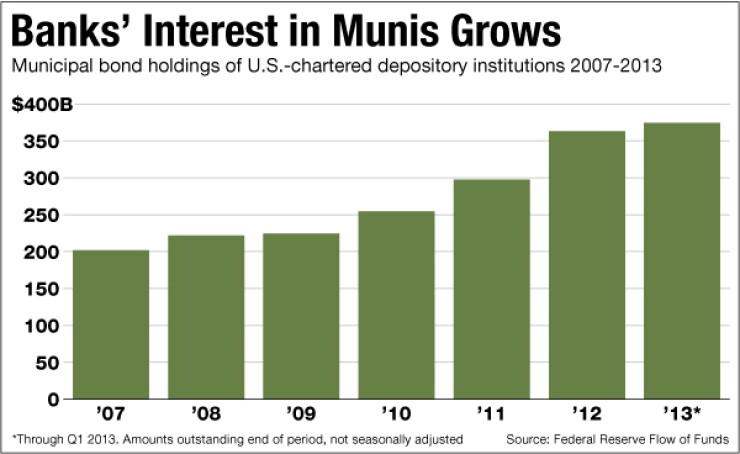

Banks’ muni bond holdings have increased to about 10% of total bonds outstanding in the $3.73 trillion market from 6% in 2007, according to the latest Fed flow of funds numbers. Through the first quarter of 2013, they’ve risen 85%, to $374.2 billion from $202.0 billion in the six years.

The change in capital treatment for the largest banks doesn’t sit well with the American Bankers Association, their trade association. It’s unclear, though, just how institutions will choose to handle it, said Cecelia Calaby, a senior vice president for the ABA’s center for securities, trust and investments.

“We don’t think this is a good thing that the larger banks have to flow unrealized gains and losses through capital, because we believe it exacerbates the volatility of bank capital in a way that is not useful or helpful to investors,” Calaby said.

When banks hold securities, they have to place them into held-to-maturity or available-for-sale portfolios for accounting purposes. Marking to market a security in a bank’s held-to-maturity portfolio is unnecessary. It’s required for those securities held in its available-for-sale portfolios.

There are two approaches to capital treatment in the new rule for banks. The advanced approach applies to banks generally with consolidated total assets of at least $250 billion, or consolidated total on-balance-sheet foreign exposures of at least $10 billion.

All other banks fall under the standard approach, which lets them opt out of the treatment for “accumulated other comprehensive income.” This amount consists of accrued unrealized gains and losses on certain assets and liabilities that haven’t been included net income, yet are included in equity under U.S. generally accepted accounting principles, such as those gains and losses on securities designated as available-for-sale, according to the specifics of the rule.

“All but the advanced approach banks can elect not to flow unrealized gains and losses through capital,” Calaby said. “We expect most will take that decision.”

Long-term muni purchases at the largest banks will be affected as a result of the accounting requirement for their available-for-sale portfolios, a managing director in the muni group at a large bank said. The largest banks control about 50% of banking assets in long-term fixed-rate municipal paper, he said, while the 8,000 banks that comprise the other half of the banking system still have the ability to buy those without having them affect regulatory capital.

“If it was believed that the top-10 banks in the country were going continue adding munis at the rate they had been adding them for the last two years, I’d guess that rate of increase in purchases has to decline with this,” the banker said.

This is because, as the value of an asset dropped, banks would have to effectively take a charge against capital for that drop in market value, said Michael Decker, a managing director and co-head in the municipal securities division of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. “And they would be able to treat as added capital an increase in the value of their assets,” he added.

As interest rates rise and banks incur unrealized losses in their muni holdings, thus reducing capital, they will have to meet their capital ratios some other way or must have buffers against those losses, Calaby said. “One technique or tool they may use to better position themselves from an interest-rate risk perspective is to shorten the maturity of the securities in their available-for-sale portfolio,” she said.

Regarding the risk weightings of GO and revenue bonds, GO bonds remain in a relatively low risk-weighting category, Sifma’s Decker said. Revenue bonds do as well, but are in a higher category than GOs.

Still, banks would have to hold two-and-a-half times as much capital against revenue bond assets as they would for GO bonds.

Sifma was disappointed that the Fed chose to disregard

“This rule, once it’s fully implemented, will affect some banks’ decisions on which municipals they might want to hold and what volume of municipals they might want to hold,” he said. “In that respect, there are going to be some market implications.”

Banks’ increase in their muni holdings has been particularly significant in the last several years, Decker said. Their participation in the market has had the effect of keeping borrowing costs for state and local governments lower than they might otherwise be.

Others in the industry said the effects of the rule changes will probably be marginal.

For one thing, many banks have regarded the rules as inevitable and have planned accordingly, said Peter Hayes, head of municipal bond portfolio management, trading and research at BlackRock. Furthermore, he added, banks are likely to view the low risk weighting of municipals relative to other securities in a favorable light.

“Across the investment-grade spectrum, munis do carry a lower risk weight than other asset classes,” Hayes said. “And some banks I talk to think it’s going to be beneficial, in terms of a contribution to their bottom line.”