When Moody’s Investors Service put the short-term credit rating of Bank of America under review for a downgrade back in February, that stirred up the water for tax-exempt money market funds.

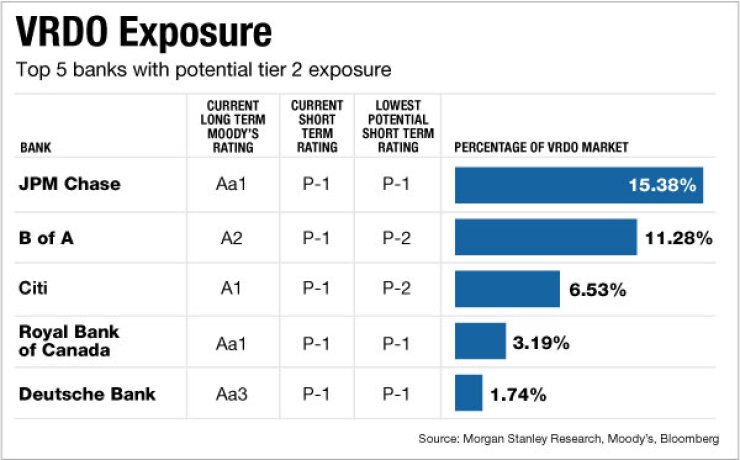

In fact, Moody’s placed the credit ratings of many large financial institutions under review. But B of A provides the credit backing for a huge amount of short-term municipal securities — variable-rate demand notes and obligations — that money market funds have purchased.

And if Moody’s actually lowers the short-term rating for the bank even one notch to tier 2 from its current tier 1 status, that could force tax-exempt money market funds to sell many of their VRDOs.

In turn, the downgrade of so large a player in the short-term market would drive down the interest rates for credits backed by the few remaining tier 1 liquidity providers. Alternatively, it would reset at higher interest rates the paper supported by the now-tier-2-rated bank.

“It will have an impact on money market funds,” said Wendy Casetta, a senior portfolio manager in the short-term space at Wells Capital Management and co-manager of the firm’s ultra-short, short-term and strategic funds. “It’s probably is going to shrink that universe of eligible letter-of-credit providers for [them].”

The numbers, mostly estimates at this point, could be significant. B of A supports around $35 billion of the short-term municipal credits that Moody’s rates, placing it behind only JPMorgan, said Thomas Jacobs, senior credit officer in the public finance group at Moody’s. That could represent about 10% of tax-exempt money market fund assets, he added.

“If [B of A] were to fall into the category where it becomes so weak that it has to be replaced, that’s a pretty big exposure,” Jacobs said. “It’s a pretty big amount.”

For its part, the bank declined to comment for this story.

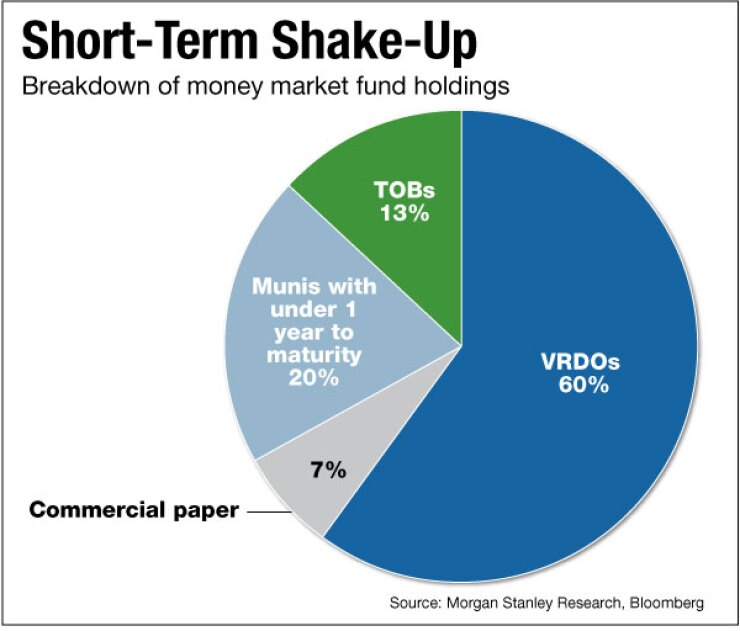

Variable-rate demand notes and obligations represent about 70% of the securities that comprise the pool of short-term tax-exempt debt available to funds, Citi muni analysts Vikram Rai and Mikhail Foux wrote in a research report.

But for those VRDNs unconditionally supported by a bank-issued letter of credit — such as by B of A — the LOC provider’s downgrade to P-2 from P-1 would have an immediately impact on so-called 2a-7 eligibility. That’s because the short-term ratings on the security are derived from the short-term credit ratings of the entity providing liquidity support, the analysts wrote.

Moody’s defines issuers or supporting institutions it rates P-1, or Prime-1, as those that have a superior ability to repay short-term debt obligations.

Securities and Exchange Commission Rule 2a-7 mandates that money market funds invest 97% of their portfolio in tier 1 securities — securities with the highest ratings. This means that demand from money market funds could not only fall, but those funds might end up unloading significant portions of VRDNs because of the change in eligibility, Rai and Foux wrote, and yields on fund-ineligible VRDNs would rise sharply.

That will burden money market funds that are compelled to sell the now-tier 2 securities with piles of cash, according to Maria Cappellano, a portfolio manager of the short-duration taxable fixed-income product at Eaton Vance.

“These funds are going to have a hard time placing that newfound cash in alternate investments,” she said. “So, you’re going to have movement from these VRDNs to a smaller base of eligible securities, which will continue to drive those rates lower. It all comes back to supply and demand.”

Morgan Stanley analysts Michael Zezas and Julie Powers calculate that at least $37 billion of outstanding debt would shift to tier 2 status if Moody’s ends up downgrading several financial institutions. As this represents 11% of currently eligible 2a-7 munis and exceeds the estimated $9 billion of tier 2 capacity of the tax-exempt money funds, it would weaken the market bid on these securities, they wrote in a research report.

This would affect issuers and investors, they added, as such a large amount of securities moving to tier 2 would likely provide upward pressure to front-end yields. Furthermore, the rating actions that could move a considerable portion of money market-eligible muni debt from tier 1 to tier 2 would severely limit the ability of money funds to hold the debt.

Subsequently, the Moody’s review of bank credit ratings could sap demand for a significant portion of existing money market-eligible muni debt. This is because 73% of money market-eligible securities are structured as either VRDOs or tender option bonds, the two wrote.

“If the ratings decline to the full extent of Moody’s guidance,” Zezas and Powers wrote, “we estimate that $37 billion to $97 billion of combined VRDOs and TOBs are at risk of significantly diminished demand.”

Finally, any downgrade of B of A’s short-term credit rating would also likely compel issuers to find new credit backers at a different financial institution, driving up their costs of issuance. It could also accelerate the growth of the direct bank-purchase market, said Rich Raffetto, head of public sector, nonprofits and depository financial institutions at U.S. Bank.

“If any major player in the municipal credit and liquidity enhancement market were to be downgraded, it will be an additional catalyst for the direct-purchase market to pick up even more,” he said, “because issuers can borrow directly from these large banks with less concern about the bank’s rating.”

Still, it’s important to consider that money market fund managers look at a number of different nationally recognized statistical rating organizations for the ratings of the securities that are purchased, Eaton Vance’s Cappellano said.

Generally, most of the major money market funds look at three agencies: the largest being Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch Ratings. As long as two out of those three rate a VRDN as a tier 1 security, it’s still considered tier 1.

“It’s when two out of the three are downgraded that you would have the biggest issue for those tax-exempt funds,” she said.

Bank of America has been under review by Moody’s for downgrade to P-2 from P-1 since Feb. 15. There is typically a 90-day window for the review, Moody’s Jacobs said, though conceivably it could last longer.