If allegations that banks manipulated Libor prove to be true, those actions likely cost municipal bond issuers with swaps linked to the rate tens of millions of dollars, according to experts.

The story harks back to the auction-rate securities crisis that erupted in 2008. Then, ill-fated ARS were hedged with swaps pegged to a percentage of the London Interbank Offered Rate, which is supposed to be a measure of how much banks charge each other for short-term loans.

Barclays Bank and others allegedly colluded to keep Libor artificially low in order to give the impression that their borrowing costs were not being affected as the financial crisis unfolded. That, in turn, had the effect of reducing payments to issuers with Libor-related swaps.

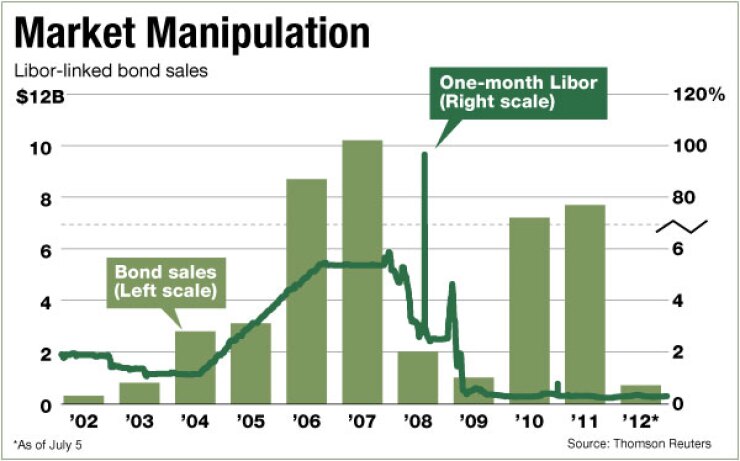

Industry estimates hold that municipal issuers have between $50 and $100 billion in Libor-related transactions, most tied to the one-month Libor rate.

The vast majority of swaps done by muni issuers to hedge their variable-rate exposure were swaps pegged to a percentage of Libor, said Sam Gruer of Cityview Capital Solutions, a financial advisory firm in Millburn, N.J. that works with interest-rate swaps and other derivatives.

The muni borrower agreed to pay a bank a fixed rate and receive a floating rate, calculated as a percentage of Libor, which was supposed to match the rate on the auction-rate security.

“So that as rates rose and their debt costs went up, the floating rate they received on the swap would correspondingly go up — that’s the expectation,” Gruer said. “And they would be left with a net synthetic fixed rate that they could budget with reasonable certainty.”

But during the auction-rate security crisis — precipitated by failed auctions — ARS yields soared far more than Libor did.

And muni issuers essentially got stuck paying the fixed rate to their bank counterparty as well as the spread between the ARS and Libor to their investors.

In doing so, they lost money, according to Peter Shapiro, managing director of Swap Financial Group LLC in South Orange, N.J.

“If Libor were artificially depressed because of manipulation by the banks, then these issuers received less under their swaps than they should have,” he said. “So, they were damaged. And those damages would likely run into the tens of millions of dollars.”

Barclays made headlines when, on June 27, it entered into a settlement with U.S. and U.K. regulators and agreed to pay more than $450 million to settle allegations that it manipulated Libor.

Representatives at Barclays declined to comment on the allegations or their impact on the municipal market.

One issuer, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, serving the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area, had an estimated $700 million in ARS in 2008 and a $3.5 billion swap portfolio, “all floating to fixed,” said Brian Mayhew, its chief financial officer.

While Mayhew said he was frustrated and dispirited to learn about the allegations of Libor manipulation, he wasn’t sure if they were the direct cause of the rate’s seemingly odd behavior during the period in question.

“The whole market seized up in 2008,” he said. “There was no liquidity for anybody, anywhere for any price, regardless of Libor. So, how do you gauge which side of the equation was the good or the evil? I’m going to have to let this one settle down a little. I can’t begin to gauge how this one affected everybody.”

Cityview’s Gruer took a stab at it.

He compared two rates to which hedged, variable-rate exposures are pegged: Libor and the SIFMA municipal swap index.

Looking at historic SIFMA numbers, it averaged around 1.75% until September 2008. Then it spiked up to about 8.00%, more than quadrupling, Gruer noted.

As the Federal Reserve pumped money into the system around November and December of 2008, SIFMA eventually settled back down to a level of around 1.00%, or less. As of Friday, it was 0.18%.

By comparison, Libor went from 2.80% to 4.82% over the same period, an increase of 72%.

“While it is clear that there was at least 50 basis points of additional basis mismatch during that time period, it is not clear whether that was due to natural market dislocations or manipulation,” Gruer said. “Either way, the cost to municipalities was high.”

The typical muni borrower with a swap involving SIFMA is paying the SIFMA rate and receiving 67% of Libor, Gruer said.

So, from Sept. 1 to Dec. 1, 2008, there was a mismatch during the height of the financial crisis in 2008 of about 50 basis points, Gruer calculated.

“There’s no question about it that there was tens of millions of dollars of basis mismatch, for [variable-rate demand bonds] that were hedged with percentage of Libor swaps,” he said.

Prior to the Barclays Bank settlement, municipal issuers had already taken legal action.

On April 30, plaintiffs, among them the city of Baltimore, filed an amended complaint against more than 15 financial institutions, including Bank of America Corp., Barclays, JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citigroup Inc. and others.

The plaintiffs alleged in the complaint that the financial institutions, from a date on or before Aug. 9, 2007, through at least February 2009, suppressed Libor in order to pay lower interest rates on Libor-based financial instruments that they had sold to investors, including the Baltimore plaintiffs.

Swap Financial Group represents Baltimore as swap advisor, the firm said, providing guidance on interest-rate derivatives used for hedging purposes.

In late June, attorneys for the defendant banks responded by filing to dismiss the litigation.