BRADENTON, Fla. — Florida Gov. Rick Scott has ordered an investigation of the state’s 1,618 special districts, some of which have defaulted on billions of dollars in municipal bonds.

The governor’s Office of Policy and Budget was ordered last Thursday to begin a thorough examination to determine if districts are operating properly, levying appropriate taxes or assessments, serving a legitimate purpose and disclosing required information.

The OPB was also tasked with recommending legislative changes to the district structure.

With billions of dollars of debt outstanding, one municipal bond expert believes the governor’s extensive probe could set the stage for lawsuits.

Scott said the investigation is part of his goal to lower the cost of living for residents, and pointed to more than $15 billion in taxpayer-funded revenues that the districts bring in each year.

“Floridians have a right to know what they’re being taxed for and how that money is spent,” he said. “This review will bring to light these questions and allow us to identify ways to save taxpayers money and increase accountability.”

The districts are special-purpose local governments and political subdivisions of the state. They are used for 70 different purposes, according to a study by Lewis Longman & Walker PA, legal consultant to the Florida Association of Special Districts.

Community development districts, or CDDs, are the most common type of district, followed by community redevelopment districts.

Other district uses include housing authorities, drainage and water control, neighborhood improvements, fire and rescue, agriculture and conservation, airports, ports, expressways and bridges.

All of Florida’s 67 counties have at least one special district, according to the Lewis Longman study.

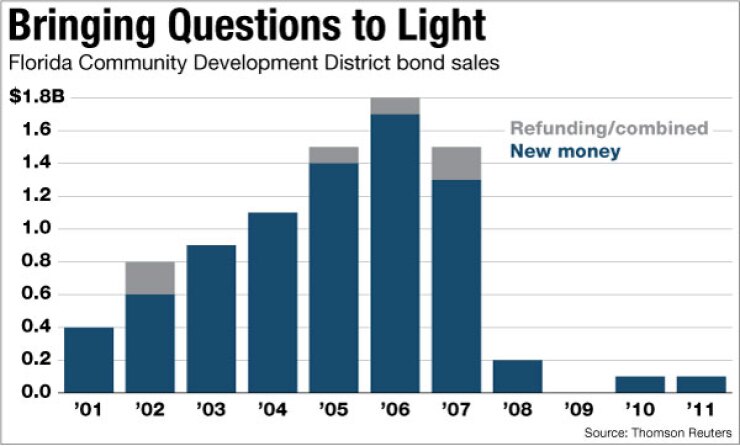

Many districts are in trouble, and the largest number in distress are CDDs that sold so-called dirt bonds, according to Richard Lehmann, publisher of Distressed Debt Securities Newsletter and the

Lehmann said Florida has the highest district default rate in the country, with 325 of them defaulting on $7.63 billion of bonds since 2006. Of those, 182 CDDs have defaulted on $5.5 billion of bonds.

The next two biggest states with district defaults are California, with 60 defaulting on $978 million of bonds, followed by 20 districts in Colorado defaulting on $346 million.

In his default studies, Lehmann typically includes issuers that dipped into reserves to make debt service payments because it is a sign of distress. However, bond covenants may not include using reserves as a default.

Districts in Florida are required to file annual financial information to the state. and they are required to report general district information to the state’s database at

However, no state agency comprehensively monitors them for compliance with bond documents, disclosures, tax and assessment levies, or expenditures.

“Some special districts have been delinquent in submitting the required information to state agencies, and thus are circumventing state oversight of their activities and preventing the transparency of their operations to the public,” said Scott’s executive order calling for the review.

The order did not indicate when the review would be completed.

“What’s important here is getting the information to see how those tax dollars are being managed,” said the governor’s spokesman, Lane Wright.

Wright said the governor is concerned about default issues, and staff is looking into the problem.

“Ultimately, in order to continue growing jobs, Gov. Scott wants to keep the cost of living as low as possible for all Floridians,” he said. “To do that, it’s necessary we hold everyone accountable who spends taxpayer dollars.”

The governor’s office provided no details about how laws governing special districts might be changed as a result of the review.

Lehmann said that could become a legal problem.

“I see this as a fault-finding inquiry which could be the basis for a flood of lawsuits on behalf of bondholders,” he said. “My suspicion is that a review of the CDD deals will discover that the main defect in these bonds is that insufficient due diligence was being done on these deals and that some of the parties to the offering were conflicted.”

Clete Saunier, president of the Florida Association of Special Districts, predicted the governor’s probe would show that districts are “fiscally responsible, community-focused local government entities.”

“Special districts have always demonstrated strong levels of accountability to protect taxpayer dollars and remain steadfast in their mission to address specific community needs, and provide and maintain infrastructure and service needs that are important for area residents,” Saunier said in a statement on the association’s website.

Saunier did not respond to a request for additional comment by press time.

Scott, who is entering his second year as governor, has already ordered examinations of the state’s public hospitals and five water management districts.

At Scott’s behest last year, the Legislature passed a bill giving it authority to determine the amount of ad valorem revenues that can be collected by water management districts.

The law also requires their district budgets to be approved or rejected by the governor.

The result has been significant cutbacks in tax levies and downsizing.

Last week, Fitch Ratings lowered the South Florida Water Management District’s $500 million of certificates of participation to AA-minus from AA, citing restrictions on the agency’s ability to raise revenues.

The governor also appointed the Commission on Review of Taxpayer Funded Hospital Districts last year, to assess if it is in the public’s best interest for government entities to operate hospitals.

The commission released its findings three weeks ago and recommended significant changes to hospital taxing districts, including a sunset review of a district’s authority to levy taxes every eight to 12 years, and periodic approval of the district by voters.

During commission hearings, some hospital administrators said that a periodic review and voter requirement could negatively affect their ability to issue bonds.

Wright said the governor has reviewed the hospital district report and is working with the districts and Legislature to follow through with a number of recommendations. He provided no other details.

Last year, as required by the state constitution ever four years, Scott appointed a Government Efficiency Task Force to develop recommendations for improving government operations and reducing costs.

The task force finalized its report in December and recommended that the Mid-Bay Bridge Authority be consolidated with the Florida Turnpike Enterprise.

The task force also recommended consolidating administrative functions of the Orlando-Orange County Expressway Authority and the Tampa-Hillsborough County Expressway Authority with the Turnpike Enterprise.

No bills have been filed concerning the hospital districts or the turnpike consolidation.

The Legislature is in session through March 9.