Harrisburg’s Chapter 9 bankruptcy filing immediately raised questions about the legality of the move as experts pondered the impact on the municipal bond market.

Pennsylvania’s capital city on Tuesday night sought protection from creditors under threat of a state takeover after grappling with how to pay off $310 million of incinerator bonds.

“What I find unusual are the very substantive disputes on authority and process without getting into the underlying economic issues,” said Alan Gover, a partner in the financial restructuring and insolvency practice at White & Case LLP.

The City Council voted 4 to 3 to file for bankruptcy, despite the city’s acting solicitor questioning the legality of the move and its mayor opposing a Chapter 9 filing. “Day 1 is going to be an interesting Day 1. All the issues of authority will be on the table,” Gover said of the court proceedings.

Meanwhile, the filing was not expected to have a negative domino effect on the municipal market in general.

“It may send a tiny shiver through the market, but it won’t have any significant impact on the market in terms of trading levels,” said Alan Schankel, managing director at Janney Capital Markets in Philadelphia. Harrisburg “has been coming down for months” so the Chapter 9 filing should not be a huge shock to the market, he added.

“Bankruptcy has been a risk for some time now,” said Anthony Valeri, investment strategist at LPL Financial. “It’s been more than a year now that the market realized this incinerator project was far too leveraged and there would need to be some sort of restructuring.”

The filing could have some impact on Pennsylvania bondholders.

“This is a very politically charged debate with the City Council defying the mayor and the state and insisting bondholders take a bigger haircut and not force higher costs on the residents of Harrisburg,” he said.

The state, which worries about a blow to its image with a filing by its capital, also wants to protect bondholders to prevent higher borrowing costs.

If Harrisburg defaults, the market may view Pennsylvania as less likely to protect bondholder interests. Investors may in turn place a higher risk premium, in the form of higher yields, on all Pennsylvania debt, Valeri said. “Harrisburg does highlight the political battle some municipal debt may become entangled in as local residents attempt to push losses onto bondholders rather than have residents pay higher fees or costs to support existing debt.”

Assured Guaranty Municipal Corp., bond insurer for the incinerator debt, said in a statement that Harrisburg is not legally allowed to file for bankruptcy, and “strongly supports the governor and the legislature to reach a prompt and fair resolution of Harrisburg’s debt obligations.”

After the council filed for bankruptcy, its attorney, Mark Schwartz, filed under Chapter 9 in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania. Chief Judge Mary France, who has served the district since 2003, has the case.

Schwartz, in an interview Wednesday, said he’s convinced the council is on solid footing, despite acting city solicitor Jason Hess having questioned the validity of the move. Mayor Linda Thompson also opposes the bankruptcy filing. “The council is the master of its own rules. It can ignore the advice of its parliamentarian,” said Schwartz, a former bond banker who runs a Philadelphia-area law firm.

The city’s $310 million of debt includes bonds outstanding on the incinerator plus balances owed to Assured Guaranty, Dauphin County, and the facility’s operator, the Harrisburg Authority.

“This latest action by the City Council is nothing more than a delay tactic to avoid making the tough decisions necessary to resolve the city’s debt crisis,” Dauphin County’s commissioners Jeffrey Haste, Mike Pries and George Hartwick III said in a joint statement.

Harrisburg’s filing comes amid attempts by state lawmakers to impose a three-member receivership panel. The General Assembly will resume debate on the legislation when it reconvenes next week. Gov. Tom Corbett favors the bill.

The filing also challenges a state law passed in June that prohibits a bankruptcy filing by a city of Harrisburg’s size that rejects a financial plan under the Act 47 program for distressed communities, under the threat of losing all state aid.

Schwartz questioned the legality of a takeover that cites Act 47, given that bankruptcy was an option when Harrisburg enrolled in the state program.

“It’s like buying a ticket to the baseball game and they changed the rules and said, 'Oops, the game’s only 20 minutes,’ ” said Schwartz. “You can’t change the rules of government with an ex post facto law.”

Harrisburg’s controller, meanwhile, thinks the bankruptcy filing will help clear a muddy situation.

“This is the best option for us to pursue,” said Dan Miller, a Thompson critic who has said he will run for mayor in 2013. Thompson did not return messages seeking comment.

Miller said the bankruptcy filing could force bondholders to the table to negotiate better terms for the city.

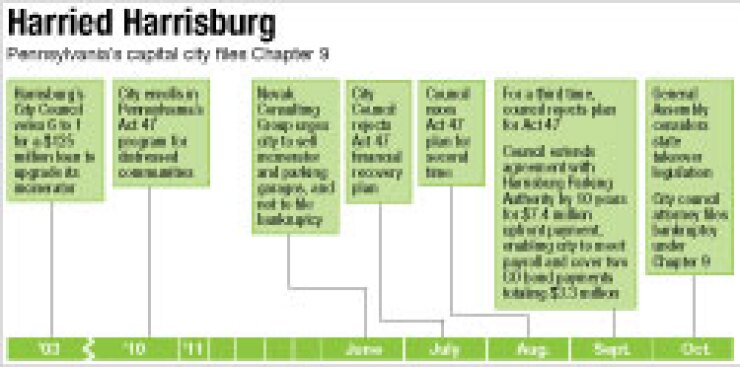

Harrisburg’s troubles began in 2003 when it approved a $125 million loan to retrofit its trash burner. Last December, after the debt escalated, Harrisburg entered Act 47. But the City Council rejected a recovery plan three times, all by 4 to 3 votes.

Council members Brad Koplinski, Susan Brown-Wilson, Eugenia Smith and Wanda Williams reiterated their no votes, while Gloria Martin-Roberts, Patty Kim and Kelly Summerford again voted yes.

Koplinski said any plan would need $100 million worth of concessions from Assured Guaranty to be workable.

Opponents of the Act 47 plan said proposed remedies favored bondholders over taxpayers. They also said they resent takeover efforts by suburban lawmakers.

“What do we do, bend over and take it?” Smith asked Tuesday.

The bond debt raises legal intrigue that will play out in bankruptcy court, said Jonathan Henes, a restructuring partner at Kirkland & Ellis LLP in New York.

“These bonds may have special treatment in Chapter 9 as opposed to general obligation bonds,” he said. “The holders of those bonds may say they’re entitled to any revenue out of the incinerator. This creates a complex situation in Harrisburg, where you have multiple parties with multiple debt — the incinerator bonds, the GO debt, and the budget shortfall.”