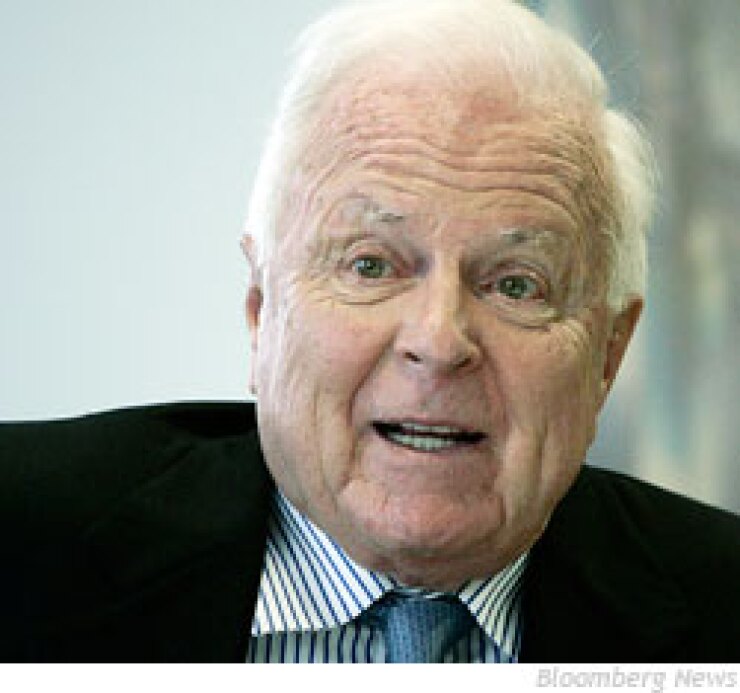

SAN FRANCISCO — Former Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan is still ringing the warning bell about municipal finances.

Riordan is alarmed by what he sees as an endemic problem, not only in California but nationally. And especially in his hometown.

He said Los Angeles, like many cities and states, faces dramatic increases in employee pension and health-care benefit costs over the next several years.

Riordan served as mayor of Los Angeles from 1993 to 2001. He believes muni doomsayer Meredith Whitney is right with her prediction that local governments are in big trouble.

“A lot of things are going to happen dramatically over the next couple of years, and then people will listen,” Riordan said in an interview. “If you close down all the parks and all the libraries, this is political dynamite.”

He said he thinks Los Angeles is headed for insolvency.

“All these problems in Los Angeles are no worse and probably better than in San Francisco, for example, which still means they are not very good,” Riordan said. City officials “have made some compromises for this year’s budget, but they really are child steps, not anything that is going to solve long-term problems.”

Earlier this month, current Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa signed a $6.9 billion budget that filled a $336 million gap mainly by cutting police and fire services, but which avoided layoffs of city employees.

Over the last few years, the city, which has a population of around four million, has fired thousands of workers and imposed furloughs to balance the budget.

Rating agencies and others have pointed to the rising costs of pension and retiree health-care benefits as the main long-term fiscal concern for Los Angeles. However, analysts are not as gloomy as Riordan, assigning double-A category ratings to the city.

The city’s pension contributions are expected to balloon to $1.28 billion by fiscal 2016, according to its own estimates.

Even though Villaraigosa has tried to rein in the rising benefit costs through negotiations, Riordan said new employees still are on defined benefits plans that the city can’t afford, especially since it estimates its costs based on an annual investment return rate of 8% for the pension systems, a figure he believes is too high.

The former mayor said the city would have to come up with between $2 billion and $3 billion over the next three years to cover the rising benefit costs, which includes the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

“Every politician in their term of office doesn’t want to take the tough steps, they don’t want to stand up to the unions and they don’t want to [file for] bankruptcy,” Riordan said.

Although he admitted he doesn’t know the best plan to get the city out of its fiscal pickle, he said he has discussed the problems with city officials.

Last year, Riordan voiced the same concerns that prompted officials to dispute his characterization of city finances and his call for Los Angeles to file for bankruptcy.

City administrative officer Miguel Santana has said the government’s financial woes are easing and the city is dealing with its pension and benefit problems.

The warnings from the former mayor are nothing new — he has been sounding them for more than a year, with Op-Eds appearing last year in the both the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times.

Riordan has come under fire from critics because his mayoral administration had negotiated some of the retirement benefit packages that the city is now trying to roll back.

But the ex-mayor, saying he never claimed to be clairvoyant, increased the union benefits as part of balanced budgets.

“We were in an affluent time in our history, which made it easier for us,” he said. “I am not going to say we were geniuses, because if I could have foreseen everything that happened I would have acted differently.”

Riordan said the state of California is in worse shape than his home city and will likely have a hard time selling revenue anticipation notes for liquidity needs next year as a result of its ongoing budget problems.

Most market experts don’t share Riordan’s extreme assessment.

“I think Los Angeles through the threat of layoffs has been getting some concessions” on pensions and health care benefits, according to Howard Cure, head of municipal research at Evercore Wealth Management. “I am not overly concerned for their general obligation debt and certainly no one is talking about them in bankruptcy.”

Cure said he is more worried about California counties and how they will deal with potential costs passed down to them by the state.

Moody’s Investors Service rates Los Angeles Aa2. Standard & Poor’s and Fitch Ratings rate the city a notch lower, at AA-minus.

Nationally, Los Angeles’ tax base is second only to New York City’s.

In its most recent report, Moody’s said the city’s general-fund revenue base is diverse and offsets relatively weak general fund reserves.

“While city revenues have declined almost across the board over the past fiscal two years, the city made significant progress in bringing its general fund budget back into structural balance this past year,” Moody’s analyst Eric Hoffman said in its latest report on Los Angeles in November.

Moody’s assigns a negative outlook to the city.

The current reserve fund balance stands at $193 million, or 4.43% of the adopted budget, according to Santana.

However, Hoffman said the city still suffers from major cost pressures due to pension and employee health-care benefits, which will be challenging over the next several years.

According to the most recent report by Standard & Poor’s, the city’s four-year outlook projects growing deficits in the face of rising long-term liabilities, mainly pension contributions.

Contributions to city worker pensions for fiscal 2012 are expected to hit $872 million and spike to $1.28 billion by fiscal 2016, Santana said in a budget update in March.

Early this year, more than 73% of Los Angeles voters approved a ballot measure to create a lower level of benefits for newly hired police officers and firefighters.

In the official ballot statement, Santana said Los Angeles would save an estimated $152 million over the next 10 years, “assuming the city continues to hire public safety employees to maintain its current workforce.”

“The city has not increased its retirement benefits in recent years, but we have observed that funded ratios have been hard hit by market performance, and changes in actuarial assumption,” Standard & Poor’s said.

Moody’s said the pension and retiree health benefits costs are the primary driver of the negative outlook on the city’s debt and present a challenge for building up reserves.

Analysts said the city has a low long-term debt burden that is conservatively structured.

Debt service is limited to 15% of revenue for all direct debt and 6% for non-voted debt, according to Standard & Poor’s. The city also has a formal 5% budget reserve goal, although the general reserves have mostly come in below that at the end of the past several fiscal years.

The city also levies separate property taxes for its voter-approved general obligation bonds that are constitutionally restricted to pay for debt service.

Los Angeles typically structures its GO bonds with level principal payments and a 20-year final maturity.

The city’s $434 billion gross assessed valuation in 2010 was more than twice that of each of the next three largest cities in the state — San Diego, San Francisco and San Jose, Moody’s said.

However, Los Angeles citizen’s socioeconomic profile is well below average among similarly rated U.S cities, with a poverty rate of 19% according to a 2006 Census Bureau survey.

The city’s unemployment rate as of April hit 11%, According to the U.S. Department of Labor.