The payments that cigarette manufacturers make to the states are dwindling as people smoke less, posing the latest setback to tobacco bonds — a sector that’s enjoyed little good news since the financial crisis.

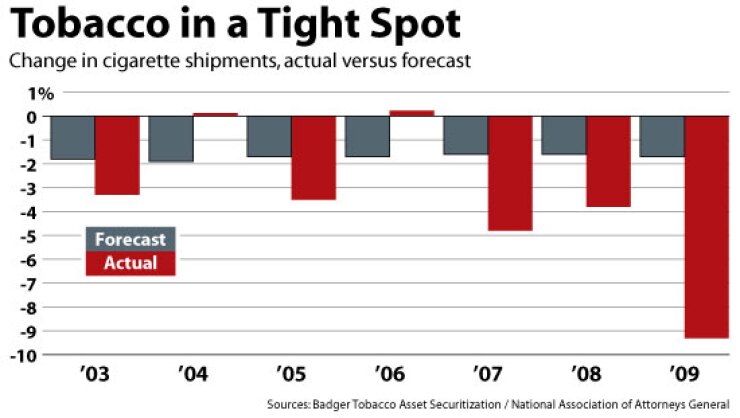

The legal settlement payments act as collateral for nearly $56 billion of bonds, according to Bloomberg LP. Most of the bond structures they support were devised assuming modest declines in tobacco consumption over time and rising settlement payments. That scenario is now in doubt, with cigarette consumption plunging 9.3% last year by one measure — about five times more than forecast.

“We saw a consumption decline that was above and beyond our base-case expectation,” said Aoto Kenmochi, a tobacco bond analyst at Fitch Ratings. “All the excise tax that went in had a really negative impact on consumption.”

The precipitous decline in payments threatens to leave some tobacco bonds outstanding longer than expected. In the worst cases, the withering payments could eventually push some bonds into default.

The tobacco bond sector was born after Philip Morris and other cigarette makers cut a deal with 46 states in 1998 known as the Master Settlement Agreement. In exchange for billions of dollars every year in perpetuity, the states agreed not to sue the tobacco manufacturers for the health hazards the industry poses.

Under the settlement, the tobacco industry was expected to pay the states more than $200 billion over the first 25 years.

Rather than wait to collect their money spread out over all that time, many states opted to sell the rights to the settlements to investors for an up-front sum, a process known as securitization.

The Buckeye Tobacco Settlement Financing Authority floated the biggest deal. In 2007, the Ohio agency sold $5.53 billion in bonds backed by all of the settlement payments the state is entitled to under the MSA.

Most states sold bonds entitled to a specified percentage of the settlement payments.

Investors are entitled to a dedicated stream of securitized tobacco-settlement payments so long as they are sufficient to cover interest and principal on the bonds. If the payments are not sufficient, the bonds default.

The interest and principal received by investors depends on the payments the cigarette makers send to the states each year. Those payments are based on a complex formula that adjusts for the size of the cigarette market, inflation, consumption and other factors.

One thing that could curtail the payments is if people buy fewer cigarettes. The formula adjusts the settlement payments downward for declines in tobacco use.

When the first batch of tobacco bonds came to market, there was a widespread belief that demand for cigarettes was inelastic — meaning smokers were so hopelessly addicted they would keep buying cigarettes even if prices rose.

When Ohio floated its bond sale in 2007, Global Insight conducted a study forecasting tobacco consumption decades into the future. The firm expected tobacco shipments to slip around 1.8% a year indefinitely.

The past few years have challenged notions about the inelasticity of cigarette demand, suggesting there may be a tipping point as new taxes and rising unemployment squeeze household budgets. The cost of a pack of smokes is poised to reach $11 in at least one state thanks to all the new taxes.

Facing a barrage of new levies on cigarettes assessed both by the federal and state governments, people have cut back on smoking far more than Global Insight forecast.

Americans smoked 325 billion cigarettes last year, according to the National Association of Attorneys General. This marked a 9.3% plunge from 2008 and a decline of 4.3% annually over the past five years. It falls short of Global Insight’s forecast by 19 billion cigarettes.

The sharp downdraft in cigarette use was reflected in the MSA payments the tobacco companies made to the states this year: $6.39 billion.

Dick Larkin, chief credit analyst at Herbert J. Sims & Co., called this figure “a disaster.” It represents a swan dive of 16.5% from last year and badly misses the “base” scenario of $8.14 billion contemplated when the MSA was first reached.

The tobacco bond structures typically set the cost of paying off the bonds at a rate lower than the anticipated MSA payments, to ensure a cushion in case settlements come in below expectations.

The Buckeye deal, for instance, allowed for the expected MSA payments in 2010 to exceed the debt service on the tobacco debt by 20%. That buffer means the bond could sustain some shortfall in MSA payments and still pay off investors.

Fitch undertook a review of the entire sector last month in response to the weakening MSA payments. The rating agency examined the ability of tobacco bonds to withstand further declines by modeling how much MSA payments could fall before a default.

A rating of B, for instance, means the bond could tolerate nothing less than a 1% average increase. A triple-B rating means the bonds could brook a decline in MSA payments of as much as 2.5% a year.

Fitch has downgraded dozens of tobacco deals in the past few days as the fading settlement payments have left tobacco structures with less of a cushion to tolerate further erosions.

“Certainly the buffer has declined over time,” Kenmochi said. “There’s a real possibility that some of these bonds will default.”

Larkin thinks so, too.

Unless things get better, he anticipates some of the riskier tobacco structures that left themselves a less than adequate fortress against dwindling settlement payments will have to tap reserves in 2024 and face default afterward.

For now, investors aren’t feeling much relief just because the bonds aren’t defaulting.

One of the biggest risks in holding securitized tobacco debt is that it will wind up maturing later than an investor thought it would.

These structures typically funnel the settlement payments to pay off scheduled interest and principal on the bonds. With whatever is left over, the structures then buy outstanding bonds from the investors before their maturity. It’s a process known as a turbo redemption, which is similar to a bond call or mortgage prepayment.

If the settlement payments continue to fall short of expectations, issuers will not exercise as many turbo redemptions and the outstanding tobacco debt will remain outstanding longer than anticipated. This is called extension risk.

Larkin said extension risk is already a reality.

Gathering data from Bloomberg, Larkin examined some of this year’s turbo redemptions.

California planned to redeem $101.5 million this year. After settlement payments to the Golden State — the biggest recipient of tobacco payments — plunged 16.6%, to $762.5 million, the state reduced the size of its redemption to $37.6 million.

New Jersey lowered the amount it redeemed to $32.5 million from an initial expectation of $79.7 million. Virginia is not exercising any turbo redemptions this year.

The slower turbo redemptions mean more debt remains outstanding, exposing investors to extension and putting pressure on the issuers, who are left paying interest on a bigger mountain of outstanding debt.

Larkin said it is clear higher taxes have taken their toll on people’s willingness to buy cigarettes.

The federal government began charging a $1 tax on packs of cigarettes last year. Five states plan to raise taxes on cigarettes on July 1.

After those are enacted, 14 states will charge at least $2 in taxes on top of the $1 federal tax.

A pack of smokes in New York will cost as much as $11 after a new state excise tax.

There is no index following the tobacco bond sector, making it difficult to assess its performance, but trading in tobacco bonds exhibited little change after the NAAG announced the plunge in settlement payments. The yield on Ohio’s tobacco bonds maturing in 2034 have jumped 65 basis points to 8.15%, but this increase is not universal.

Michigan’s tobacco bonds maturing that year have actually improved 12 basis points to 7.3%, and New Jersey’s tobacco bonds have improved 35 basis points to 7.2%.

Joseph Darcy, who manages a high-yield municipal bond fund at Hartford Investment, said investors anticipated a tumble in MSA payments this year and baked expectations for sicklier collateral into the bond yields in advance. If anything, the payments were less dire than people feared, he said.

Since the announcement, spreads on the riskier deals have bled out even more, anticipating further weakening in consumption, Darcy said.

“The trend toward lower consumption is going to continue,” he said. “When they were originally putting these deals together, the excise tax on cigarettes was a matter of pennies. Now, you’re getting into areas where you have a meaningful impact of taxes, much more than was originally anticipated.”

Darcy said the tobacco sector is bifurcated by vintage.

According to Thomson Reuters, most tobacco bonds hit the market in one of two major waves: the first in 2003, and the second beginning in 2005 and cresting in 2007.

The first wave of bonds was underwritten more conservatively, Darcy said, with more realistic expectations and a stronger bulwark against declines in MSA payments. The second wave, which coincided with the credit bubble, suffered from more wanton standards and less security for the bonds, he said.

For example, the 2007 Buckeye deal established a 20% cushion of expected MSA payments exceeding debt service costs in 2010. By comparison, consider the $1.59 billion Badger Tobacco Asset Securitization, which in 2002 sold off the rights to Wisconsin’s share of MSA payments. The expected MSA payments for 2010 exceeded scheduled debt service costs by 39% — almost double the cushion of the Buckeye deal.

Within the sector, Darcy regards the earlier vintages as relatively safer and the later ones as more dangerous.

While he declined to specify whether he has been shedding tobacco bonds from his $412.8 million fund, he did say he has been “dialing back the risk meter” overall.

At the end of May, three of the fund’s five biggest holdings were securitized tobacco deals — including both the Badger deal and the Buckeye deal.